The Princes’ Islands (Adalar) are a chain of nine small islands in the Sea of Marmara, about 20 km east of the center of Istanbul. They are a popular destination for tourists and Istanbulites alike looking to escape for a day from hectic city life, especially in the summer season. Once there you can rent a bike, hop on a horse-drawn carriage or swim on their beaches. Of the nine islands, only four are accessible to the public: Büyükada, the biggest and most popular, Burgazada, Heybeliada and Kınalıada. This last one, Kınalıada, is probably the least popular due to its small size and dearth of well-known attractions. However, if you enjoy discovering un-touristy, hidden gems, I recommend that on your next trip to the Islands, you get out at the first ferry stop and visit Kınalıada and its unusual mosque.

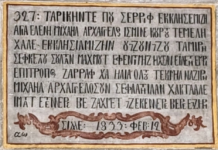

The Kınalıada Mosque is situated right along the coast, to the left as you exit the pier. It is visible from the sea, with its outstanding minaret and angular shapes, when coming on the ferry from Istanbul. The history of this mosque goes back to 1958 when the mosque of Karaköy, known as the Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Paşa Mosque, was dismantled on account of city planning. The materials of the mosque were numbered and transported to Kınalıada by ferry in 1963. The new mosque was designed by Başar Acarlı with the collaboration of Turhan Uyaroğlu. Small in scale and almost hidden behind unaesthetic shops, the building’s futuristic shape immediately takes you by surprise; this is far from the traditional mosque shape, which seem to pile up on the mainland.

After strolling through the main avenue for a few minutes, you will see to your left a low stone wall and a sign over the entrance to a small garden. The surrounding façade of the free standing building has been disappointingly cannibalized by shops like a supermarket, a realtor’s office and a restaurant. Historically mosques always had a complex around them (külliye) that consisted of schools, hamams or hospitals, among other facilities. But in this case, the sloppy manner in which the shops are attached to the mosque diminishes the quality of the space. Moreover, folding canopies have been added to the terrace giving the impression of a simple bar terrace. A permanent pergola in the modernist style of the building would have made for a more integrated complex.

The mosque has the shape of a white truncated pyramid. This V-shaped roof is the defining element of the mosque. The gap between the two levels of the roof is closed with a stained glass window featuring simple floral motifs. This plain but elegant shift of the roof allows the indirect daylight to enter inside the small prayer space. In a much more humble scale and intention, the architectural solution resembles the one used in a contemporaneous building: the Sydney Opera House. In both cases, setting aside the difference of scale and use of the buildings, a series of structural shells – inspired by their location near the sea – cover the space and allow the light to enter through their cracks.

Without leaving the garden the other interesting element that we find is the minaret. Originally designed for the muezzin to stand on when singing the call to prayer, minarets are not functionally needed anymore due to the use of speakers. Nevertheless, it has become an essential architectural component of the mosque design, and is still regarded as a requirement due to its symbolic meaning. In this case the minaret is a self-standing structure, freed from the main building. The shape avoids the traditional cylindrical missile-like form and presents a geometrical and slender prism tower. Considering this is a 50-year-old building, the shape of the minaret is certainly radical. It has a plastic value that provides a very avant-garde look and the use of an exposed concrete texture is reminiscent of a Brutalist style. This polyhedron icon becomes a symbolic element and a landmark for the mosque.

The interior space is a very small room with room for only a few people. What captures your attention immediately is the pyramidal roof. Upon entering the stained glass cannot be seen but the light bathes the pyramid walls, creating a sublime space conducive to silence and prayer.

This modernist mosque with slanted shapes raises an issue for debate: does a mosque in the 21st century still need a dome? We can maybe find the answer if we replace the word “mosque” with “church” and “dome” with “cross plan”. The answer, then, is that it doesn’t.

The dome and the cross plan are reminiscent of much earlier periods of architecture: the central dome has its origins in Ottoman times and the cross-in-square in the Byzantine era. The latter was a fundamental aspect of Christian architecture, but is no longer dominant. There are many excellent examples of contemporary churches that disassociate themselves from the cross plan. For instance, in Japan we can find the Church of Light by Tadao Ando, designed as a concrete cube, or in France there is the classic chapel at Ronchamp designed by the master architect Le Corbusier.

Yet designers of mosques seem more reticent to employ new shapes that may inspire holiness but with a contemporary line. Nowadays the main elements and organizational schemes from the classical Ottoman mosques are still preserved. (On occasion you may find some of them constructed with modern materials.) This is due in part to the restrictions placed on architects by their clients and how the already established traditional forms have accumulated in the collective memory. Fortunately, some architects of mosques in Turkey have begun to incorporate originality and innovation in their designs as a way of contributing to the development and progress of religious architecture. We can find some examples of this in Istanbul, like the Sancaklar Mosque by Emre Arolat. However, the Kınalıada Mosque achieved this contemporary status 50 years ago, which makes this small gem all the more valuable. On your next trip to the Islands, stop off in Kınalıada and discover for yourself this unique mosque that was well ahead of its time.

Santiago Brusadin is a contributor to Yabangee

[…] pretty dumbfounded at how many fools haven’t made the trip over. Make it a May goal to visit all four, or be all trendy and organize a staycation at one of the haunted-looking houses with some crazy […]