Mimar Sinan was, without a doubt, the greatest architect of the Ottoman empire. His importance and influence are often compared with his contemporary Michelangelo, and it’s an established fact that Mimar Koca Sinan (“Great Architect Sinan”) was one of the most prolific architects of all time. Istanbulites and tourists know him as the architect of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul and the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne — his masterpiece — but he also designed more than 350 works, including mosques, mausoleums, hospitals and hamams, all over the lands of the Ottoman empire.

While his major works show the pinnacle of Mimar Sinan’s artistry, I am personally more interested in his hidden gems. Some of his smaller and lesser known designs are an excellent opportunity to experience his architectural achievements in a more intimate — and less crowded — way than his well-known pieces. One of my favorite “less famous” Sinan buildings is the Şemsi Pasha Mosque.

This tiny mosque is located in the district of Üsküdar near the ferry docks. Tourists who cross to the Asian side through Üsküdar often just visit the mosque just opposite the docks, the noteworthy Mihirimah Sultan Mosque, also designed by Mimar Sinan. But only a short walk from the docks in the direction of the Maiden’s Tower is the Şemsi Pasha Mosque, which is informally known as Kuşkonmaz, or “the mosque where birds don’t land” — a result of the strong winds coming from the north through the Bosphorus that hit the building hard.

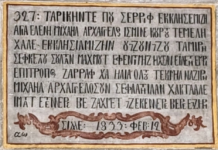

The mosque was built in 1580 by Mimar Sinan, when he was already 90 years old. While this may seem surprising to some, the period from 1570 to his death is known as his master stage. It was in this period that he experimented with the central dome space and brought Ottoman architecture to a new level of excellence. The Şemsi Pasha Mosque, which was built at the same time as another of Sinan’s famous mosques, the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque in Tophane, was designed for the grand vizier Şemsi Ahmet Pasha. In addition to serving as the Grand Vizier, Şemsi Pasha occupied other numerous high-ranking political posts, including a stint as the Ottoman governor of Damascus.

When it comes to the mosque that Şemsi Pasha commissioned, it’s not its size that makes it interesting, but rather its location and composition. This religious building has a privileged and peculiar position right by the Bosporus shoreline. Mimar Sinan had always paid special attention to the site and its surroundings, and adapting the proposed building accordingly. This architectural complex is no exception as it is specifically adapted to the strait shore. While the mosque is rotated to face the direction of Mecca (southeast), the L-shaped madrasa — a religious educational institution currently used as library — is orthogonal to the shore. The positioning of the mosque related to the madrasa — a key feature in Islamic architecture — helps to organically settle the complex on the site without disturbing the skyline of the coast. The way the building takes advantage of the lay of the land is a classic display of Sinan’s distinct style.

The mosque is integrated into a complex — called a “külliye” — that includes a twelve-domed madrasa and a classroom at the center of the western wing and projecting beyond the madrasa wall. The madrasa was recently restored, and behind the arcade columns, the library space is closed off by a full-length tinted glazing system. The image of glass panes behind the historical arcades makes for an interesting contrast between historical and contemporary architectural features although some details, such as the air conditioners against the glass and certain junctions, could have been carried out more carefully. The domed spaces of the madrasa are now used as a part of the storage space of the library. The calamitous addition of plastic bathrooms by the entrance deserves special mention, mainly because they are an atrocity. Such a sloppy addition really takes away from the renovation.

The space between the axis of the mosque and the madrasa decked wings creates an enclosed courtyard at the front and back of the mosque. The forecourt functions as an entrance garden to the complex and holds a small graveyard that prefaces the mosque. In this compact burial site, the tombstones are topped by stone hats that depict the deceased’s occupation (those buried here were mainly military or government officials). The courtyard is visually connected with the Bosphorus through decorative grill openings, and it’s not unusual to find people sitting on the benches and reading in the quite atmosphere. The back court is used as a courtyard to access the mosque and the recently renovated madrasa. It’s an oasis of serenity that prepares for the silent activities of praying. Previously the mosque bordered the sand beach, allowing fishermen to arrive with their boats and enter straight into the mosque to pray through a path leading to the entrance.

There is an entrance portico at the mosque’s north and east sides that mirrors the L shape of the madrasa. The interior of the mosque – and its single minaret instilled in one of the mosque’s corners – is modest and reflects the fact that its founder only occupied the position of Grand Vizier for six months. The interior is a small single-domed space of eight meters in diameter with beautiful upper windows that are richly colored. A glazed ceramic ovoid imitating an ostrich egg decorates the central chandelier. (Fun fact: real ostrich eggs were formerly used in the chandeliers in order to repel spiders and avoid cobwebs inside the mosques.) It is perhaps the smallest mosque built by a Grand Vizier, but it gains prestige from being located on the waterfront.

Adjacent to the mosque there is the Semsi Pasha’s “türbe,” the founder’s tomb, projecting towards the Bosphorus. This adjacency is an unusual feature in Ottoman mosques, as the tomb is usually detached from the main building. Its cavetto vault — a concave molding whose outline is a quarter circle — is also a peculiar characteristic that differentiates this mosque from others in the city, and one more reason to make a trip to Üsküdar and visit this little gem of Mimar Sinan’s.

Special thanks to Alpaslan Ataman, architect and author of “Bir Göz Yapıdan Külliyeye” for sharing his immense knowledge in Ottoman architecture for this article.

Santiago Brusadin is a contributor to Yabangee

[geo_mashup_map]

Lovely article, Santiago – can’t wait to visit.