First Encounter, September, 1964

I arrived at Sirkeci Station on the Orient Express — the real Orient Express, a train that was anything but express or luxurious. I had missed a connection on the way from Italy, ending up in Thessaloniki, so I arrived in Istanbul a day late, missing the family who were to be my foster parents while I was a student at Robert College Yüksek. I was utterly at sea, knowing hardly a word of Turkish, let alone how to get around this huge city of 3.5 million people. Cell phones hadn’t yet been invented. I do not remember how I contacted my friends, but eventually they picked me up, and I ended up at the beautiful Robert College campus overlooking the Bosphorus, just north of Bebek. I was not an exchange student; at the invitation of friends, I intended to spend a year, then transfer back to the USA, where I planned to study chemical engineering. My academic path didn’t work out as planned, and I ended up spending the two most wonderful years of my life as a student at Robert College.

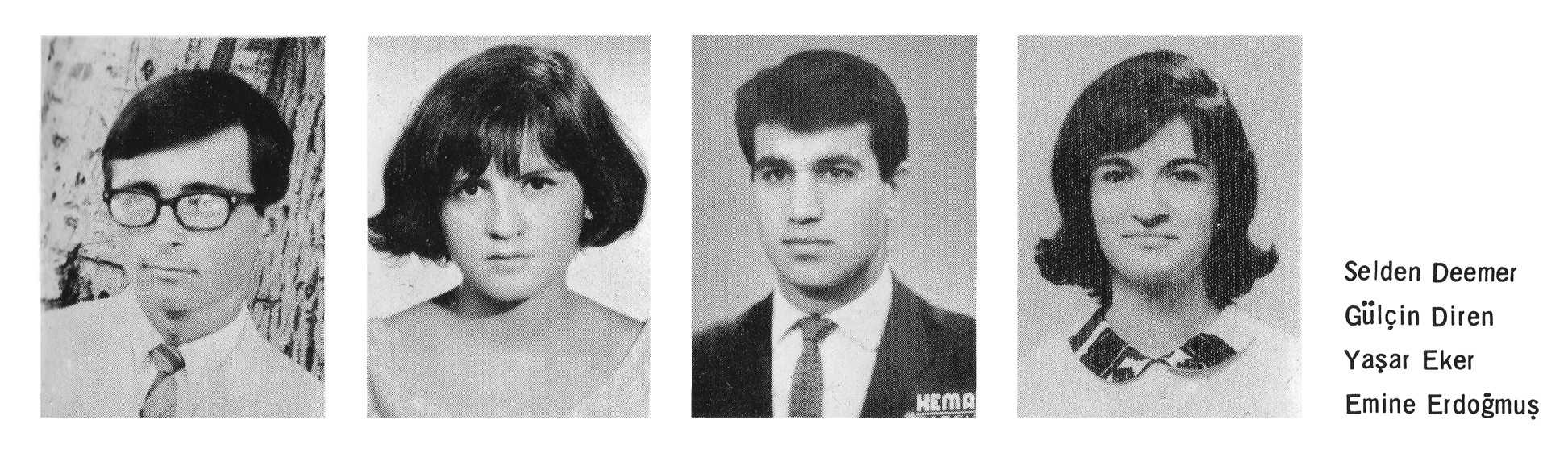

During registration for classes and dorm room assignments, I met my future roommate, Cengiz. We were assigned a small room on the inside of Hamlin Hall, top floor. In my second year, another roommate joined us in an outward facing room, also on the top floor. Although there were bathrooms on each floor of Hamlin Hall, the showers were in the basement — a long hike, especially in winter.

In the mid-1960’s John Freely and Hilary Sumner-Boyd were gathering materials for what eventually became Strolling Through Istanbul, which remains the greatest guidebook ever written about Istanbul. Every Wednesday, a note would go up on the bulletin board near the post office in the administration building, announcing the upcoming weekend’s “stroll.” Thanks to these two, I walked more than 100 miles over two years, and gained a knowledge of Istanbul’s geography that still served me well nearly 60 years later.

In the mid-60’s, Robert College had around 600 students, including the graduate division. Although I excelled in chemistry, I failed miserably at calculus. I quickly realized that engineering was an unlikely career path, so I switched to the humanities program. After my sophomore year, I transferred to the University of Michigan, where I majored in Turkish and Arabic, then went on to graduate school at UCLA, where I intended to get a PhD in Ottoman History before realizing that 1) the language requirements (Turkish, Arabic, Persian, Osmanlıca, Greek, and German) were overwhelming; and 2) jobs for PhDs in Ottoman History were scarce to nonexistent. Instead, I became a librarian, a decision I have never regretted.

As a student, I spent many afternoons and evenings at Nazmi’s, a small cafe overlooking the Bosphorus on the north side of Bebek. So many afternoons drinking beer or wine, eating şiş kebap, börek, and fried potatoes, followed by the long climb back to campus, occasionally inebriated. It’s a miracle that I survived my second year with a decent GPA.

I never lost my love for Istanbul’s culture, food, or people. In 1977 my wife and I traveled through the Balkans, again on the Orient Express — which if anything was even more decrepit than it had been in 1964. Second class train travel in the heat of summer with gypsies and livestock is an adventure. We spent a few nights in the old city, exploring the usual tourist destinations, Ayasofya, Sultanahmet, Kapalı Çarşı, etc. Istanbul was hot, humid, and noisy. Due to a municipal ban on horns, drivers pounded on the doors of their cars to announce their displeasure in Istanbul’s chaotic traffic, which if anything had grown worse since 1966.

Fast Forward to 2020

In 2020 we decided that a trip to Turkey would be a good way to celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary. I purchased round-trip tickets from Atlanta on THY in February, and made a reservation through Homestay for the first two nights after our arrival. Then the coronavirus pandemic changed the world — possibly forever. First, our Homestay hosts canceled, then THY gave us travel vouchers, and we decided to put our travel plans on hold. In January of 2022 the pandemic finally seemed to be on a course that would permit safe travel by spring, and we started to plan a new trip, staying in Istanbul, starting just after Şeker Bayram.

The delay was a blessing. In 2020, I had planned an overly ambitious itinerary that involved driving thousands of kilometers around Anatolia. We were able to use the intervening two years to study Turkish, giving me an opportunity to reacquaint my brain, ears, and tongue, while allowing my wife to start from nothing other than her experiences with other languages. At first, having previously studied Russian, she said “Turkish is so easy!” Regular grammar, no gender, Latin alphabet. Then she discovered agglutination…. Living outside a small town in north Georgia, classes and conversation were not an option at the local university, but in the 21st century the web offers so many online learning opportunities. Babbel was our favorite learning app, but after a year I had run through every lesson they offered.

To rekindle my language skills after decades of neglect, I started watching some of the hundreds of YouTube “walking tour” videos through various parts of Istanbul. I also began watching the Diriliş Ertuğrul historical drama series. Initially Ertuğrul was for ear training, but I continued to watch because it was such a compelling story — even though the series was a highly imaginative retelling of 13th century Turkish history, more legend than fact. With English captions and playback slowed to 0.75 of normal speed, I could follow most of the dialog — occasionally even predicting what the next line would be (often merak etmeyin). By the eve of our trip, after watching the first 41 episodes of Ertuğrul, my Turkish was about as good as it was going to get on this side of the Atlantic.

Welcome to Istanbul, May, 2022

THY offers direct flights from Atlanta to Istanbul, but it’s still an 11-hour trip. After checking in at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Terminal we went out to the departure gate, where the waiting area was nearly full with a multinational crowd on their way to Istanbul. Two women behind us were speaking Arabic. From their accents, I thought they were Levantine; confirmed by conversational references to Beirut. While we were waiting, I overheard two young women of college age speaking Turkish. Although they were far more fluent than me, I noticed that one of them spoke Turkish with a distinctly American accent, which I found amusing. Boarding was orderly, and the long flight, while tiring, was uneventful. THY has become a world-class airline since the 1960s.

The new Istanbul airport in Arnavutköy (a name that initially confused me, because the only Arnavutköy that I knew was on the Bosphorus, adjacent to Bebek) makes Atlanta’s international airport terminal look provincial. What a change from flying out of Atatürk Airport in 1966!

I remained in touch with the Homestay family from 2020, and we had become friends through email and videoconferencing. My new friends got to practice their English, and I was able to practice reading, writing, listening to, and speaking Turkish at a distance. They live about 10 km from the new airport, and invited us to spend our first night with them. Unlike 1964, when I arrived a day late and had no way of informing my host family, in the 21st century I had a cell phone, and I was able to call our friends before we left the international arrivals terminal. We stayed at their home Saturday night, and got to meet their two teenagers and new baby. I was most at ease speaking Turkish with the baby.

After a night with our host family, my old roommate Cengiz called. He had offered to take us to our lodgings in the Galata area, but on Sunday morning he told us that he had caught a nasty virus (but not covid), felt terrible, and was quarantined. Our host family immediately offered to drive us to where we would be staying for the next 11 nights.

I knew that Istanbul had grown from 3.5 million people in the mid-1960’s to more than 15 million today, so I was not surprised by how the metropolis had spread northward, but the modern highways were a revelation. In the 1960’s, the road between Bebek and the old city was two lanes of cobblestones, and paving with asphalt had just started. Dolmuşes and decrepit buses rattled over the rough pavement, and were our connection to the city.

As we drove into the city, everything looked very different until we reached Taksim, where old landmarks began appearing. From watching dozens of Istanbul walking tour videos on YouTube, the area where we would be staying already looked familiar. After passing the Şişhane Metro stop, we turned down Galip Dede, and I knew where we needed to turn next. I thought our driver had made a wrong turn, but who was I — an American who had not been in Istanbul for 35 years — to offer driving advice to a local? We got lost.

Eventually we parked, got out our bags, and started hiking (uphill, of course) toward Şimşir Sk, Beyoğlu, a few hundred meters from Galata Kulesi. Despite carrying luggage, it was a cool day, and we had a pleasant hike past both familiar and unfamiliar landmarks. After losing our way a few times, we ended up at the Meroddi La Porta Hotel, which managed the flat we stayed in for the next 12 nights.

Istanbul has changed, except it hasn’t. I immediately felt at ease in Beyoğlu. While it was bustling with tourists, most were Turks, not Americans, Russians, or Arabs. At hotels, restaurants and shops, most of the conversations we overheard were in Turkish. Even with 15 million residents, Istanbul remains a wonderful walking city, but the steep streets, traffic, and unexpected obstacles on sidewalks require eternal vigilance. Belatedly, I bought an Istanbul Kart, and we started using trams and ferries to go farther afield. Instead of the arduous climb from Karaköy to Galata, we could take the Tünel tram, exit at the Istiklal Caddesi station, and walk downhill on Galip Dede. What a treat! In the 1960’s, getting around relied almost exclusively on buses and dolmuş taxis. Of all the changes over nearly 60 years, Istanbul’s contemporary transportation system is one of the most welcome. Ferries, metro trains, and trams are clean, frequent, and inexpensive.

Street Animals

Five years ago I watched a documentary film, Kedi, which captivated me. While watching Kedi, I thought it was just about 7 Istanbul street cats and the crazy cat people who looked after them. After watching many YouTube videos, I gained greater appreciation for and understanding of the deep cultural roots that Turkish society has for street animals, especially cats and dogs. I am sure there were thousands of street animals in the 1960s, but I don’t really remember them, possibly because I spent most of my time as a student at Robert College. They say that in a city of 15+ million people, there may be as many as 250,000 street cats — perhaps many more.

People unfamiliar with Istanbul think these cats are feral. They are not. They are community cats, belonging to nobody, but cared for by all. A few days after our arrival, I bought a 300 gram bag of cat food at a Migros Jet market. Whenever we set out on a walk, the bag of cat food was in my backpack, and if I saw a cat without food, I would stop and set out some food for it.

My penchant for handing out cat food created a minor tourist attraction at the Hamuşan of the Galata Mevlevihanesi Müzesi. In a few minutes a gathering of hungry cats drew a crowd to watch the cat party outside the graveyard.

Adventures with Turkish

As we explored the city, I had opportunities to use my still limited, but serviceable Turkish. In any country, few things open more doors than using a few words in the local language. Turks, after their initial surprise at hearing a foreigner speak their language, were delighted to engage in conversation. In the 18th century Dr. Samuel Johnson remarked, “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on its hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised that it is done at all.” A foreigner speaking Turkish — especially an American — provokes a similar reaction. One morning while I was sitting at the base of the Çemberlitaş column, an old man approached me and said “Good morning,” to which I responded “Günaydın. Nasılsınız?” He broke into a smile, and we had a pleasant conversation about how I had come to learn Turkish, while he talked about his son, who was studying in the United States.

After a few days, I found myself defaulting to Turkish when greeted, whether in English or Turkish. Once, near the Grand Bazaar, an especially aggressive tout accosted me in English. When I responded to him with Teşekkürler, he said, “Don’t thank me. Buy something!” When speaking Turkish, I noticed that I pronounced my name as “Selden Demir“. Even though neither my given name nor my surname is the least bit Turkish, it just sounded more natural.

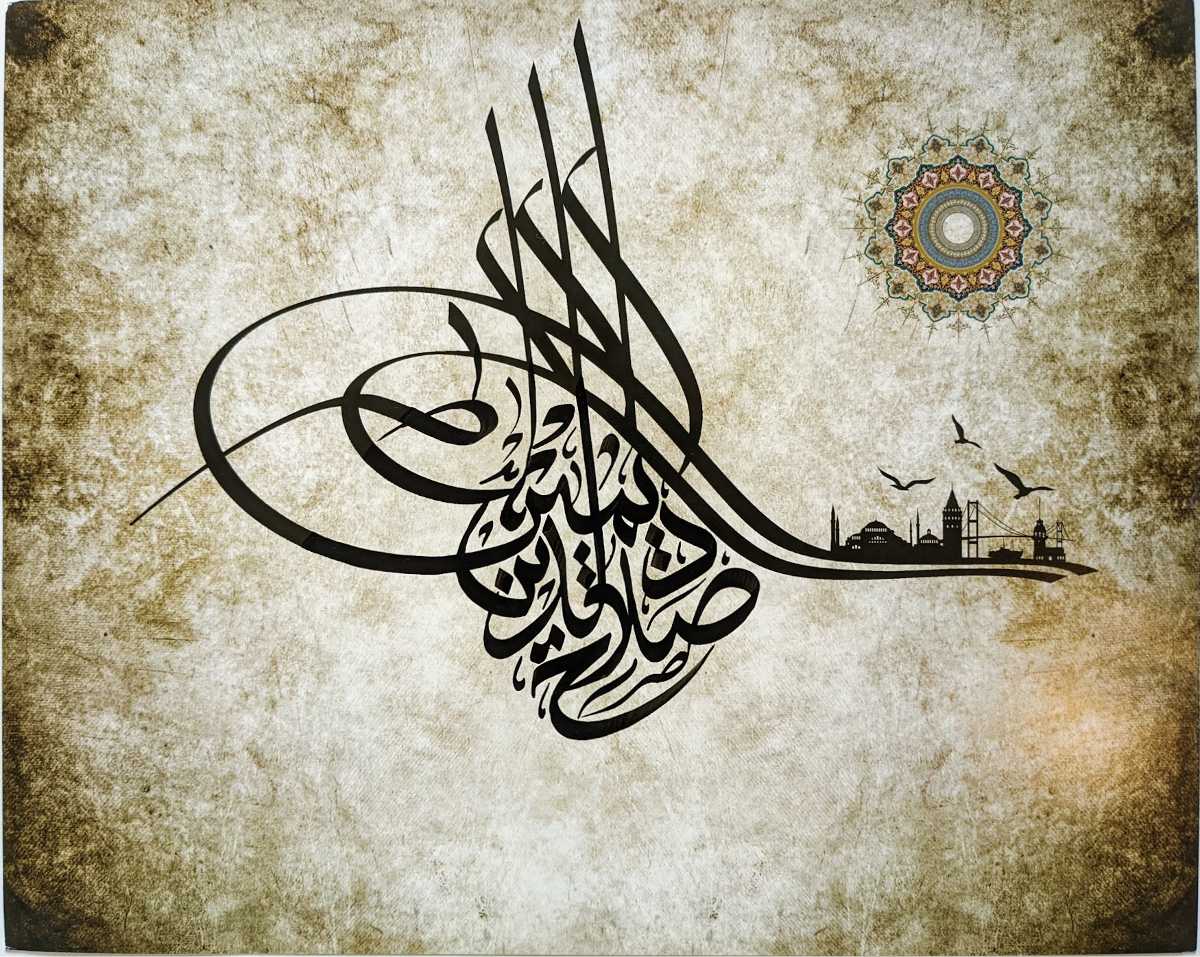

In 2019, I took a course in Arabic calligraphy, an art that requires both discipline and practice. As a retired person, I had ample time to practice, spending hours each day, starting with a page of nuktas, then alifs, etc., working through the alphabet. Even after I felt I had gained reasonable control over my pens, I would start a writing session with warm up exercises.

Eventually, I tried fitting my name into an Ottoman tuğra, a task that turned out to be far beyond my limited calligraphic skills. While studying calligraphy, I learned about Istanbul calligrapher (and composer, musician, and film director) Muhammed Başdağ, who has a small shop, Hat Yazi, near Çemberlitaş.

Fulfilling my dream, I commissioned my very own tuğra. We took some liberties with my name, substituting Salah al-Din for Selden, but the end result far exceeded my expectations.

In 1964, I knew almost no Turkish, but on this trip someone said that my Turkish was about as good as Dr. Mehmet Öz. It was a left-handed compliment, perhaps, but I don’t have Turkish parents, I haven’t served 2 years in the Turkish army, and I had hardly used the language in more than 50 years, so I was flattered.

After my student days at Robert College, I went on to study both Arabic and Persian. Despite language reforms under Atatürk, a significant number of Arabic and Persian loanwords remain in Turkish. Things that once puzzled me — such as why some words are pronounced or spelled the way they are — are much more easily understood now that I can recognize them as loanwords.

Even more than the linguistic foundation, after nearly 60 years I now possess a depth of cultural knowledge that I lacked as an 18-year old who had never been outside the USA. While watching an episode of Diriliş Ertuğrul, this line of dialog appeared: “There is no sword other than Zulfiqar and no valiant other than His Holiness Ali.” Not only did I know about Ali and Zulfiqar, but I recognized the phrase as having the same cadence as the shahada, the Islamic profession of faith. In another scene, Ibn al-Arabi says to Ertuğrul, “Son, do you know who Hızır is?” I did. I regret that we didn’t arrive in Istanbul until after Hıdrellez, the spring festival associated with Hızır, had ended. Despite greater cultural awareness, I managed to step on my tongue when I told someone that I thought Atatürk was the only good autocrat of the 20th century, an attempt at a compliment that fell flat.

Aside from being much larger than it was in the 1960’s, Istanbul in 2022 feels far more cosmopolitan. I heard Turkish being spoken with Arabic, Chinese, and African accents. There seemed to be far more Turkic people from central Asia. While riding a tram one day, I overheard a woman with Asiatic features speaking with someone on her cellphone. I could follow much of what she was saying — often punctuated with anlamadım — but when she turned to her husband, even though she was still speaking a Turkic language, almost all comprehension vanished. And the names of businesses! So many international brands, Benetton, Gap, Guess, Nike, Skechers, Tommy Hilfiger, Burger King, McDonalds, Starbucks, and on and on. I confess, I do not understand why so many young Turks like to hang out at Starbucks, when Turkish coffee is so much better. It must be a prestige thing.

May 18 was our last full day in Beyoğlu. My old roommate Cengiz called to say that he would pick us up on the 19th and take us to Bebek, where we would be staying at the Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Bebek Kapı Misafirhanesi. I asked Cengiz if he knew how to find where we were staying. He assured me that Yandex would get him there. Out of an abundance of caution, I sent him an email the night before, including increasingly detailed maps of the maze of streets around Galata Tower, down to the final 100 meters. He was supposed to pick us up at 11:00. At 11:20 my phone rang. “I’m lost.” I handed my phone to someone at the hotel desk. He provided some instructions. Twenty minutes later, my phone rang again. “I’m still lost.” “Where are you?” “Galata Kulesi Sokak, near the eye hospital. “No problem, that is very close. We will walk over and meet you there.” The hotel clerk graciously helped us carry our bags. When we arrived, Cengiz yokmuş. He eventually found us, and we set off through Istanbul traffic to Bebek.

Boğaziçi Üniversitesi and Bebek

Robert College is now Boğaziçi Üniversitesi, Güney Kampüsü. The campus guest house, recently restored, proved to be a wonderful place to stay for the last two nights of our trip, with a magnificent view of the Bosphorus from the balcony of our room on the third floor.

The climb from the Bosphorus is still steep and long, and at age 75, I had no desire to walk up. Fortunately, Cengiz drove us up. So many buildings look unchanged from the outside, the bust of Atatürk behind Hamlin Hall stıll gazes out over the Bosphorus, and the campus remains one of the most beautiful I have ever known.

The climb from the Bosphorus is still steep and long, and at age 75, I had no desire to walk up. Fortunately, Cengiz drove us up. So many buildings look unchanged from the outside, the bust of Atatürk behind Hamlin Hall stıll gazes out over the Bosphorus, and the campus remains one of the most beautiful I have ever known.

The interior of Hamlin Hall, the old men’s dorm, has been extensively remodeled. There is now a security checkpoint at the entrance. The lowest level, where motorcycles used to park, is now a food court. A new floor above is now a study area.

How Bebek has changed! In the 1960’s it was more like the post-WW II Bebek of Joseph Kanon’s novel, Istanbul Passage. In 2022, Bebek is one of the trendiest spots in the entire sprawling Istanbul megalopolis. Once again, watching walking tours on YouTube was good preparation, and I felt immediately at home, even though today’s Bebek is so different from the place I remembered from decades ago. I even knew where the local Starbucks was. We avoided it, and had breakfast at Espresso Lab instead.

Nazmi’s cafe is long gone, replaced by modern apartment buildings and luxurious villas. Its role as a student hangout seems to be filled by Taps Bebek, a brewpub near the BU gate house.

Afterword

I turned 76 shortly after returning home. After nearly 60 years, Istanbul remains my favorite city in all the world. In the 1960s, Americans didn’t believe me when I told them that Istanbul was cleaner than most American big cities. In 2022, this seems even more true. In the 1960s I felt utterly safe wandering around the city at night (even in some seedy places on bar crawls), and I felt equally safe in 2022 — far safer than I would feel in any large city in my own country.

Thanks for the memories, Istanbul. I love you. İnşallah, we will return next year.