By Sam Gimson

Past and Future is a new chronological arrangement of Istanbul Modern’s permanent collection, featuring works by many of Turkey’s most significant artists. It includes 90 previously unshown pieces and some of the gallery’s most recent acquisitions. For those of us who are unfamiliar with the history of Turkish modern art, this exhibition serves as an enlightening introduction, proving the style to have been both culturally distinct and yet decidedly in-step with Western developments.

The newly-founded Republic of Turkey’s cultural reforms and secular values gave rise to dramatic shifts among young artists. By the late 19th century, Ottoman culture had become tiresomely conventionalized and was in need of reinvigorating. As demonstrated by the Dolmabahçe Palace, the Ottoman aristocracy had been increasingly adopting and incorporating occidental aesthetic values, and artists began adhering to the similarly trite conventions of the West. A number of competent life drawings by Halil Paşa, one of the first Turkish Artists to have studied in Paris and assumed these academic practices, serve as something of a prologue to the exhibition.

Its narrative is, in summary, the transition from modern to contemporary art, from the fledgling nation’s early aspirations of modernity and then, with the paintings of the social-realist movement, the resulting clash between eastern and western social and economic values. Moving into the post 1960’s contemporary art scene, more global issues are addressed, incorporating new mediums of expression such as video art and installation. We see from here a return to certain principles of the Islamic tradition.

From the pictures in the opening rooms, scant reference is made to the nation’s Ottoman Islamic heritage – this was probably in an effort to forget it. Government grants for young artists to study in Paris between 1910 and 1914 acquainted Turkish artists with impressionistic conceptions of painting. Indeed one could almost mistake these pre-war artists for Parisians. But the application of the impressionist language to Turkish landscapes and aspects of light graced their work with a certain national character. The intellectual energy of that time was far more concerned with what Turkey could become than with trying to identify with what it was.

Continuing through the exhibition, with the effects of cubism establishing themselves, we see the artists of this generation such as Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, in a work called Coffee House (1973), very much identifying with Turkish culture. In this solemn picture four individuals are portrayed, one of whom is playing a bouzouki; their total involvement in this shared experience of listening to the song must resonate with every Turkish person, or indeed any person who has ever on some melancholy summer’s evening taken comfort in music and companionship.

During the 1960s and 1970s the pace of industrialization accelerated. As the exhibition progresses, we see traditional agricultural methods and lifestyles in conflict with the modern world and the pull of urbanization. Turan Erol’s painting, The Coal Yard (1927), shows horse-drawn vehicles in a ghost-like haze before the billowy smoke of an industrial plant. And in the sad faces in Nuri Iyem’s painting titled Peasant Women (1976) a question seems to hang over the darkening landscape behind them.

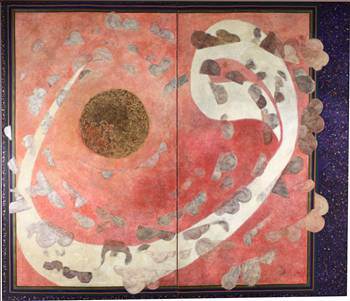

Turkey’s re-adoption of non-representational art holds well with the Islamic tradition of Aniconism; this is most beautifully exemplified in the work of Erol Akyavaş, whose abstract painting, Mansur Al-Hallaj (1968), was for me perhaps the highlight of the show. Standing before this square shaped work, which is itself a kind of diptych, proximately comprising two canvases, we are swept up by the sheer scale of the painting into a vortex, a vehement counter clockwise gesture that encircles a brown sphere. The work reminds us of the pilgrims’ circumambulation of the Kaaba and its overall effect is similar to those mystical Calligraphic roundels of the Hagia Sophia.

Since the 1960’s the Istanbul Biannual has become a well-established event among the art world’s hectic schedule of soirées and corporate orgies. Turkey like everywhere else has enjoyed the fruits of inflated art prices and foreign investment. Today, young Turks are far enough removed from their ottoman heritage to look back at it impassively, as though it were a Byzantine relic. In the final room, these artist’s references to Ottoman geometry have about as much in common with their original principles of beauty and of unity in multiplicity as western European artists do today with the classical tradition of the nude.

‘Past and Future’ grants us a marvelous opportunity to see the trajectory of Turkish modern art unfold. Whatever one makes of the work itself, I think it would be hard not to find the show interesting.

Istanbul Modern‘s new permanent exhibition Past and Future is on display now.