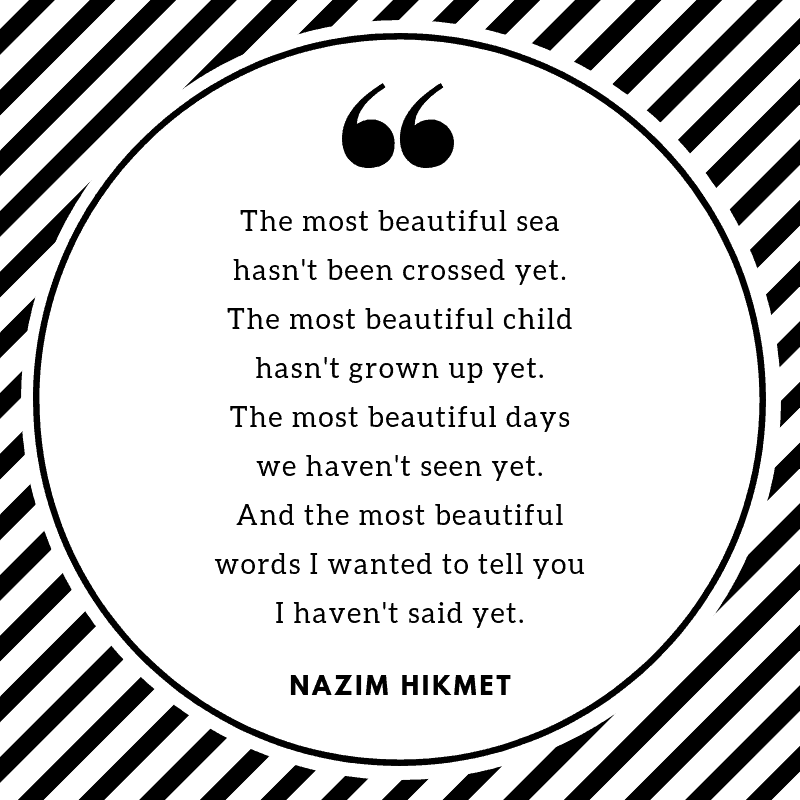

Born on the 15th of January 1902 in Thessaloniki, where his father was serving as an Ottoman government official; Nazım Hikmet Ran, commonly known as Nazım Hikmet, was a Turkish poet, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, director and memoirist. Best known for his intellectual pursuits and considered a romantic communist and revolutionary, he was very active throughout his life in pursuit of the values he held dear.

Had I been born much earlier, he might have been my komşu, that is, my neighbor, when he was a child. His first school was the Taşmektep Primary in the street of the same name in Göztepe, Istanbul, where I live. From there he went to the Galatasaray High School in Beyoğlu for a brief time where he began to learn French. However he was transferred to the Numune Mektebi in the Nişantaşı district in 1913. His school days coincided with a period of great political upheaval, during which the Ottoman government entered the First World War, allying itself with Germany. After Nazım graduated from the Ottoman Naval School on Heybeliada, one of the Princes’ Islands located in the Sea of Marmara in 1918, he was assigned as a naval officer to the Ottoman cruiser Hamidiye. This career only lasted a short time because he became seriously ill and was permanently exempted from naval service in 1920.

Luckily for the world, illness didn’t stop him for long. In 1921 he went to İnebolu in Anatolia with a group of friends including Vâlâ Nûreddin in order to join the Turkish War of Independence. From there he walked with Nûreddin to Ankara, where the Turkish liberation movement was headquartered, and was introduced to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. He requested that Nazım and Nûreddin write a poem to invite and inspire Turkish volunteers in Istanbul and elsewhere to join their struggle. This poem was much appreciated, and they were appointed as teachers to the Sultani college in Bolu, rather than being sent to the front as soldiers. Not surprisingly their communist views were not appreciated by the conservative officials in Bolu, and so the two decided to go to Batumi in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic to witness the results of the Russian Revolution of 1917, arriving there on the 30th of September 1921. Then, in July 1922 the two friends went to Moscow, where Nazım studied Economics and Sociology at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in the early 1920s. There, he was influenced by the artistic experiments of Russian Futurists and Symbolists, as well as the ideological vision of Lenin.

On his return to Turkey, Nazım became the charismatic leader of the Turkish avant-garde, producing streams of innovative poems, plays and film scripts. Due to the political nature of his works he was repeatedly arrested for his political beliefs and spent much of his adult life in prison or in exile. In the 1940s he became a controversial case among intellectuals worldwide, so much so that in 1949, a committee that included Pablo Picasso, Paul Robeson, and Jean-Paul Sartre, campaigned for his release.

On the 8th of April 1950, Nazım began a hunger strike against the Turkish parliament’s failure to include an amnesty law in its agenda before it closed for the upcoming general election. This caused a stir throughout the country. Petitions were signed and a magazine bearing his name was published. His mother Celile began a hunger strike on the 9th of May, joined by renowned Turkish poets Orhan Veli, Melih Cevdet and Oktay Rıfat the next day. In light of the new political situation after the 1950 Turkish general election, held on the 14th of May, the strike was called off five days later on the 19th of May, the Atatürk, Youth and Sports Day. Nazım was finally released through a general amnesty law enacted by the new government.

On the 22nd of November, 1950, the World Council of Peace announced that Nazım Hikmet Ran was among the recipients of the International Peace Prize, along with Pablo Picasso, Paul Robeson, Wanda Jakubowska and Pablo Neruda. Despite this honor, Nazım continued to be imprisoned for his beliefs until he moved to the USSR, first escaping from Turkey to Romania on a ship via the Black Sea. Sadly, Nazım died of a heart attack in Moscow on the 3rd of June, 1963, at 6.30 am while picking up a morning newspaper at the door of his summer house in Peredelkino, far away from his beloved homeland. He is buried in Moscow’s famous Novodevichy Cemetery, where his imposing tombstone is still today a place of pilgrimage for Turks and many others from around the world. His final wish, never carried out, was to be buried under a plane-tree (çınar ağacı) in any village cemetery in Anatolia.

Despite his persecution by the Turkish state, Nazım Hikmet has always been revered by the Turkish nation. His poems depicting the people of the countryside, villages, towns and cities of his homeland, as well as the Turkish War of Independence, and the Turkish revolutionaries, are considered among the greatest patriotic literary works of Turkey. His life and ideals live on in the Nazim Hikmet Culture and Art Foundation located in Kadıköy on the Asian side of Istanbul. Established by his sister Samiye Yaltırım in 1991, it initially housed a collection of books, articles, and other published works by or about Nazım Hikmet, and numerous letters, correspondence and other ephemera pertaining to the poet. The aim was to contribute to the advancement of art, culture and education in Turkey and around the world. Over the years the purpose of the foundation has branched out and now the center hosts films, recitals, book readings, symposiums and many other events.

To learn more about this great Turkish poet, and to read some of his work yourself, click here.

All photos courtesy of the author.