The Galataport has finally opened – some of it anyway.

This immense 1.7 billion-dollar project along the shores of Karaköy on the city’s European side has been in the works for several years. When it’s finished, it will be a shopping mall-cultural-commercial-port by the sea. One of those complexes with a lot of hyphens. The vision? Huge cruise ships and luxury liners, filled with tourists, will pull up at the dock, and all these tourists will disembark, eager to spend their money in all the shops and cafes sitting right there just steps away from the pier.

The other day my wife Özge suggested we go there and check it out with our son Leo. There was a Monet exhibit in the newly opened museum, which is also located on the site. Walking from the pier in Karaköy, we navigated a good half mile along the waterfront. We passed the areas still under construction, and the old Istanbul Modern, which has been closed during the construction but is expected to reopen soon.

It was a lot to take in. But having lived in Istanbul the past decade, I have grown used to these massive projects. There was the Marmaray, the metro which runs beneath the Bosphorus, the third span bridge up near the Black Sea, the new international airport, and the canal project, which is expected to break ground soon. And those are just some of the biggest projects.

Throughout the vast city, you stumble across new shopping centers, metro lines and apartment blocks. At times, the city feels like the epicenter of some never-ending construction site. Even on our street in Üsküdar, the two apartments on either side of ours have been knocked down and completely rebuilt over the past two years.

Back to the Galataport. The expensive, ambitious vision is, as I said, not fully realized yet. When it is done, it will boast the world’s first underground terminal (a hatch system), along with office space, a 2,400 car parking lot and will bring in an estimated 25 million visitors a year. As the official website boasts, “(T)his historical city harbor (will be) a world-class cruise liner port and touristic destination, while opening the promenade to public use for the first time in approximately two centuries.”

At this point, the complex is complete enough that you can really get pretty clear idea. The architecture is all low rise, with sharp post-modern edges. Aesthetically, it stands in direct contrast to the Galata Tower, which for centuries has been the most visible symbol of the neighborhood, as well as to the classical architecture of Dolmabahçe Palace, which is located further down the waterline. The neighborhood of Karaköy itself was modeled after Venice, that great shipping port that served as a rival for the Ottomans in the battle for supremacy in the Mediterranean.

These days, the scale of the Galataport makes it clear that the Turkish government wants to again make Istanbul’s port and the Bosphorus an important global sea port (which is puzzling, isn’t it already that? One sees container ships bound to and from China and other points, every day, along with every other kind of vessel). Well, with the Turkish lira down 10 to 1 against the dollar, and inflation on the rise, let’s hope that these ambitions bear fruit.

Walking through the complex, my wife and I (with Leo in his stroller) went in search of the Monet exhibit. Along the way, we passed a lot of finished sections, with signposts directing visitors to the various blocs. We passed a D and R bookshop, as well as jewelry and clothing shops. At one point, outside a sweet shop, a man wearing a red Ottoman fez called us and offered a bite of lokum, or Turkish delight, which he cut from a long strip. We waved him off and continued on.

“It would be nice if they offered a place for people to have drinks,” my wife Özge said.

And so they have. We walked out to the impressive promenade, where you could see the ships passing in the blue Bosphorus. Most places are still rather empty, but people were sitting at outdoor tables, drinking pints of beer and glasses of wine and squinting at the sea under the harsh noon sunlight.

“Wonder how much a pint costs,” I said aloud. It is a pricey area, the Galataport notwithstanding. Doubtless, the prices in these fine cafes will be set in tune with the wallets of the tourists, with their dollars and euros and sterling, not we poor Istanbullus and our weak liras. To put it in perspective, a 40-lira pint of beer is for us very expensive, but for a visiting American it’s only 4 bucks, very reasonable.

At any rate, we weren’t there to sit and have drinks. We walked on in search of the Monet exhibit. We found it at last in the O Block. The museum is impressive, a bold, modern design painted bright green. Although we sucked in our breaths a bit when we found out the tickets were 50 lira each, we saw that the queue wasn’t too long so we decided, why not?

With the tickets in hand, we entered the darkened spaces of the interior. A lift took us up to the second floor, where more alluring darkness waited. At last, we entered a space where we could discern the shapes of people sitting or standing beneath rows of big screens. Music drifted in from speakers, and presently images began to appear on the screens, familiar Impressionist images but also photography from that era, the late-19th Century Industrial images of railroads and factories that stood as a background against which the color and light of the Impressionists can be better understood.

We saw the famous lilies, the sunset and sunrise portraits of gritty urban life, the movement of water, the floating imagery for which Monet is justly famous. Of course, it was a digital exhibit – to my initial disappointment, you’d think if they had all this money for an ambitious port they could at least fork over the cash to get a few real Monets on loan from the Monet Museum in Paris – but I quickly let these snobby thoughts go and let my senses fall into the light and shadow world of the Impressionists.

For the record, the exhibit was called, “Monet and Friends,” so there were other works on display from contemporaries such as as Cezanne, Pissarro, Renoir, et al. Also, the music playing as the images unfolded like colorful apparitions included the works of Debussy and Tchaikovsky. Indeed, one of my favorite moments from that afternoon was of our son Leo standing in front of this image of ballerinas dancing and fluttering on tip toes in a circle to the famous melody from “Swan Lake.”

Alas we were running out of time. Leo enjoyed the novelty of this dark theater-like atmosphere, and the dancing images, but he was difficult to keep in check. We wanted to get him home in time for his afternoon nap. So after a rather brief, flurried visit, we had to bid adieu to Monet and friends, and make our way out of the darkness back out to the bright streets. We walked out to the main road and stopped at a park, where we bought some seeds from a covered lady and let Leo feed the pigeons. They came in a large greedy flock, gobbling up the seeds as Leo dropped them from a pudgy hand, before they all flew upwards in a big burst, and disappeared through the autumn leaves overhead.

We kept walking until we reached Kabataş, where we got the ferry back to our neighborhood Üsküdar on the Asian side. The ferry was not crowded, and we were tired, tired from all the walking around and from absorbing all the sensations and new things we had seen.

Still, it felt rewarding to have seen the Monets, albeit digital, to have passed a Friday afternoon in the company of the Impressionists. By the way, the exhibit will be around until the middle of December, if you happen to be in the city and curious enough to check it out.

And it felt good to have gotten some first impressions of Galataport as well. Hopefully in the future, as the port comes fully online and continues to improve, there will be more and even better exhibits. Who knows? Maybe one day they’ll even have real Monets. Wonder how much we’ll have to pay for that? Oh well, money isn’t everything. I recalled a quote I’d seen on a wall at the exhibit. Not sure if it was from Monet or one of his friends. “There are two paths in painting: the broad and easy one, and the narrow and difficult one.” For some reason, that quote just stuck in my head. Maybe I took it in terms of art, or maybe in terms of living in Istanbul, or maybe as a parent or teacher. In art and life, nothing worthwhile ever comes easy, or cheap.

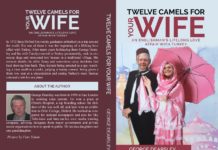

James Tressler, a former Lost Coast resident, is a writer and teacher living in Istanbul.