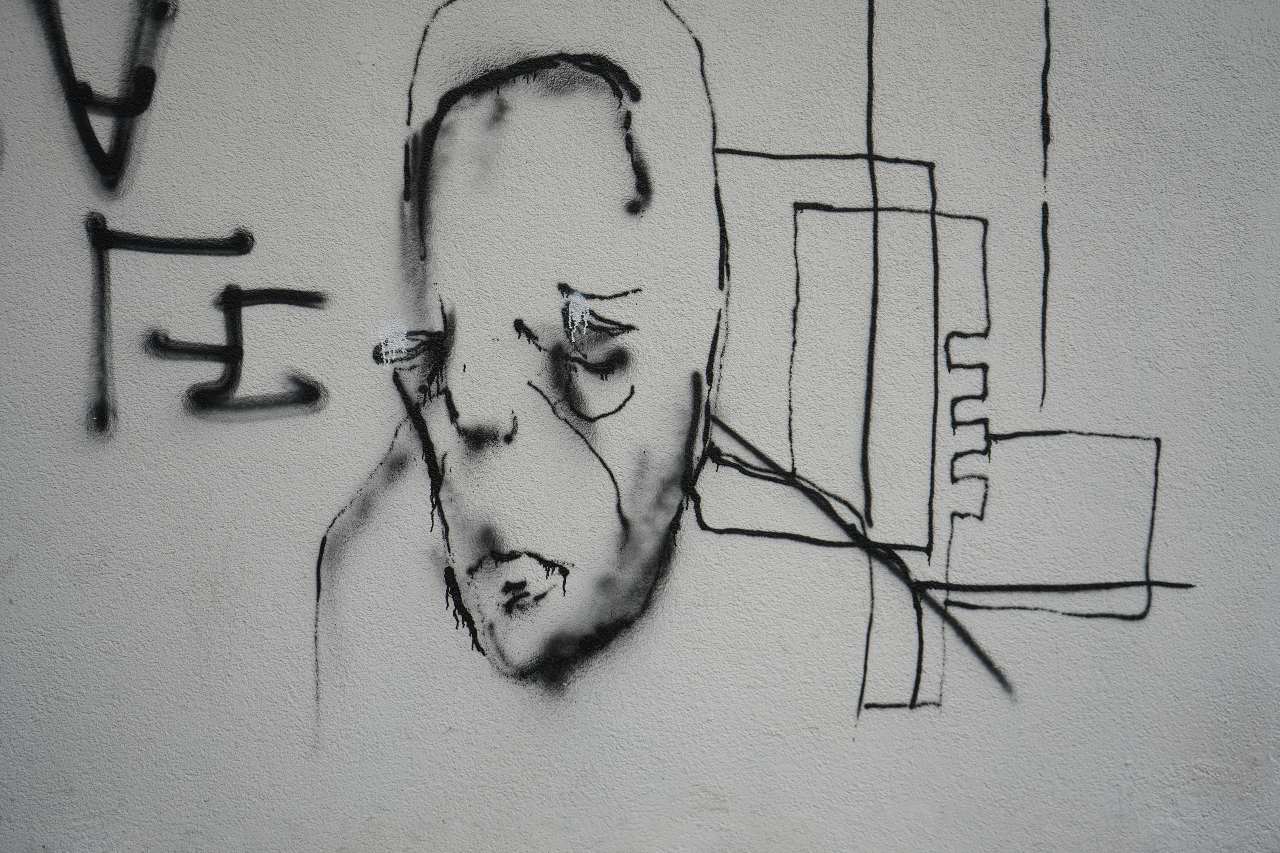

The first time I came across the signature ‘Yabancı’ was when I stepped out of my house to do the privileged walk during the pandemic. As I came outside, the sun’s rays felt blinding, hard to bear with my eyes as if I was an inmate released to the recreation area after a long detention. I remember blinking unintentionally until I got accustomed to the natural light, then a drawing emerged in front of me.

A broad elongated head carrying a pair of eyes filled with woe, a furrowed face. “Such a great congruent expression for these days,” I thought. The next thing I noticed was the name Yabancı, a word by which I was called many times. I was a yabancı myself, a foreigner, a stranger maybe. I was immediately intrigued, both by the drawing and the artist’s mark.

I would count down for the curfew to end so I could stroll down the block, hoping to find more of that sullen look in the neighborhood. After all, I needed something to attach me to the outside world, and this was some sort of a game that I defined for myself. In the beginning, they were scarce, and I could barely locate them, but as days went by and the quarantine restrictions became loose, the Yabancıs got easier to discover.

Most of these figures are drawn in the least reachable places, on an elevated wall of a dilapidated building or a chimney. Following these locations gradually made me think that the artist probably tends to choose forgotten spots as his canvas. This inclination to accentuate neglected things is not epitomized only in the drawing’s setting, but it is also applicable to the subject of them. The figures themselves mirror the outcasts, the overlooked individuals.

These portraits simultaneously resemble humankind and differ from it. Malformed heads, extended limbs, and torsos seem exotic, whereas the despair in the eyes, the scowl, and the anguish borne by these figures are familiar to our contemporary life. Aside from their abnormality in forms, how many of us appear just like them? Lonely, distressed, and exhausted. If you ask me, even the size of the skull is not bizarre; all the thoughts, concerns, and ifs we endure on a daily basis require a large amount of space. Imagine if our heads could stretch to the extent of our worries, then Yabancı artworks would be considered realistic.

Another aspect of these paintings that grabbed my attention is the method with which they are drawn. They look like doodles: quick and tentative. There is also a distinct shakiness in the outline of Yabancı’s figures which is a shared characteristic among some street arts and should not be mistaken for the artist’s lack of adroitness. Hadn’t it been for the condition in which these pieces are created, they would have seemed more stable or perhaps permanent. But the thing is, unlike the art shown in galleries or museums, these drawings are not born to be perpetual. Their longevity is as long as the authority is informed to cover them.

During one of my strolls, I stopped by a wall and showed one of the pieces to a friend of mine. “You know, yabancı also means alien,” she remarked. I didn’t know, but this interpretation gave me a better understanding of the figures and the artist’s signature. I realized how synonymous the name and the drawings are. Aside from the controversy of alien existence, these creatures displayed on Istanbul’s walls are, in fact, aliens, not taken off from a UFO, though, but they are considered outsiders, alienated by society. They are everywhere but not seen, and Yabancı reminds us of their being if only we learn where to look.

All photos taken in Caferağa, Kadıköy and courtesy of the author.