The city of Karaman stands on the low wheat plains of Anatolia, about an hour south of Konya, the birthplace of Rumi.

Arriving from Istanbul, you immediately feel absorbed by the vast spaces, the broad, flat lands with the mountains in the distance. The absence of traffic and noise, the whistle of winds coming from the prairies, reinforce the feeling of isolation. Here lies the heartland.

With a population of about 150,000, Karaman is a prairie town. The streets are lined with low, weather-beaten buildings and tenements, many of which looked as if they had been slapped together from the hard-bitten earth. Eventually the streets lead to broad squares and plazas, as well as to the inevitable covered bazaar stretching several blocks.

These rather modest appearances aside, Karaman has a long and storied history, as I was soon to learn.

My wife and I were in town for the weekend to attend an engagement party for a distant cousin on her father’s side. Arriving late Friday, and crashing at her grandmother’s apartment, we got up early Saturday and decided to kill a few hours before the party by having a look around.

Özge’s father, Vehbi, is a retired archaeologist and collector of Anatolian toys. He was perfectly suited to be our host and guide. We followed him over to the local tourism office. Inside, an exhibit helped bring us up to speed. The exhibit combined wax sculpture with 3D and virtual reality. I was introduced to Karaman’s founder, Karamanoğlu Mehmet Bey, for whom the town was named back in 1256. Prior to Mehmet Bey’s arrival, however, the Byzantians, the Romans, the Selcuks (not to mention Barbarossa), and the Armenians had all laid claim to the area.

“The Karaman clan was just one of many clans back in those times,” my wife explained. “The Ottomans were a clan too. They were just the ones that ultimately won out. Actually the Karaman clan was one of the only ones that resisted Ottoman rule. Also Mehmet Bey passed a law that banned the speaking of Farsi and Arabic. During his time, only Turkish could be spoken in Karaman.”

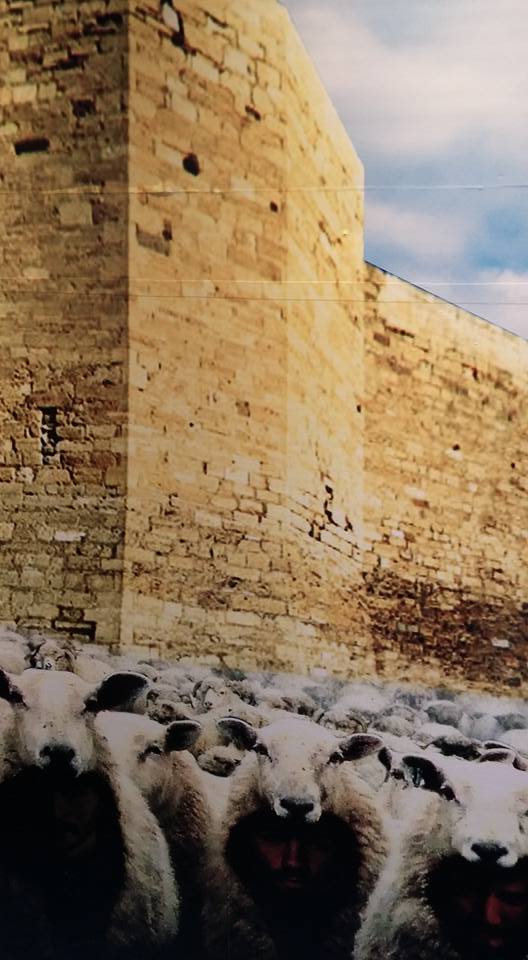

We looked at the wax visage of the old clan leader, with his dark, curly beard and fierce eyes. Later, we took in other great personages, including Piri Reis, a 14th Century Ottoman admiral and cartographer whose maps of the world rivaled those of the West in their scope and accuracy; the poet Yunus Emre, another local boy. Kazim Karabekir, general of the Ottoman army during the first World War, and Ataturk’s close associate. In another room, we encountered a 3D image of the Sheepskin Soldiers of Karaman. The story goes that back in the day, Karaman castle was besieged by an invading clan. These soldiers donned sheepskins. Under this disguise, they entered the enemy’s campsite during the night and slaughtered the invaders. The story, a cross between the Trojan horse and the hominem about a wolf in sheep’s clothing, has become a source of great civic pride. Why? Perhaps it speaks to the resourcefulness and resiliency that define not only the Anatolian spirit, but of prairie people the world over: protecting the heartland against the hostile forces of the outside world.

But this is all so much encyclopedic shit – most of which can be found with a quick Google search. We need something more personal. How about if I became a dervish? You can, here in Karaman, sort of.

At the museum they have one of those cardboard cut-outs, where you insert your head over the body.

At my wife’s urging, I donned the conical cap, which the museum guide handed over obligingly. It was tight fit. How did they whirl with those things on their heads? Maybe dervishes had small heads.

I got in position, and into character, throwing my head back, assuming a look of spiritual abandon. My wife and father-in-law, laughing with great amusement, angled for photos. Nearby, the wax statues of Rumi and his mother carried on their silent rumi-nations. Thankfully, their backs were turned. Oh well… I’ve never been much on Rumi anyway – a bit too flowery; my taste runs more toward Nazim Hikmet – but my mother loves his work so the photo was largely for her benefit back in the States (upon seeing my dervish transformation on Facebook later, a Kurdish friend wryly posted, “First you need to learn philosophy!”).

We left the museum, and went for a walk. It was sunny, and many people were out walking, shopping, sitting in the cafes – a typical Saturday.

“It feels conservative here,” I said, observing the number of women wearing headscarves, as well as the lamentable absence of bars and tekels.

My wife shrugged.

“I don’t know,” she said. “To me, it doesn’t feel any different from Üsküdar.” Üsküdar is a fairly conservative district in Istanbul, not far from our neighborhood.

Özge’s father, Vehbi, took us to the historic Tarman house, which belonged to a wealthy local family. The exterior was typically modest, a reflection of the local disdain for ostentatiousness. But the inside was richly textured and sumptuous. Chandeliers hung from the dark, wood-paneled ceilings, and spacious rooms offered sofas for visitors to relax and admire pictures of Ottoman and Karaman history adorning the walls.

Here, more wax-like figures added “life-like” atmosphere, including a poet-musician, who I dubbed Galip. He was reclining on one of the sofas, a lute laying against his chest.

My adventure as a dervish still fresh, perhaps I was suddenly suffused with some passing Sufi mysticism, for I said:

“Well, well, Galip Bey… Shall we wax poetic?”

But if old Galip was listening, he had nothing to say.

Further on, walking through hard-packed dirt roads, we passed an Armenian church, as well as a white house with a robin’s-egg blue door, where a Greek president’s family once lived. These places serve as visual reminders of the city’s criss-crossed heritage. Both the Armenians and Greeks were eventually exiled following the Turkish War of Independence. And then there was a pre-Ottoman church, built by the Karaman clan, sometime in the 13th Century. The key architectural difference, my wife pointed out, is the absence of domes inside. Instead, the ceiling is wooden and flat.

Churches, mosques, historic houses, info cards detailing historic events – these thing don’t usually interest me, not for long anyway. Even the Vatican in Rome got a bit dull after a certain point. I’ve always preferred streets, people, good things to eat and drink, especially drink. We would have plenty of those things at the party later.

That evening, we arrived at the Kent Hotel for the engagement party. The hotel was owned by another of the family’s relatives. In fact, I recognized him from our engagement party two years before.

“Do you remember me?” he asked, stretching out his arms.

“Of course!” I said.

“Bacanak!” he said, embracing. “You can call me ‘bacanak.’ You know what that means, right?”

“It means something like ‘brother-in-law,’” my wife said, translating. It’s pronounced “bahj-a-nak,” by the way.

“Ah, yes,” I said. “OK, bacanak!”

This was a word I would remember later, even after all the drinking and dancing later, for I would be forced to say it many times. It became like the buzzword, or catchword, of the evening. To everyone, I was the bacanak. The whirling yabanci bacanak. The foreign brother-in-law who earlier that day had posed as a dervish (oh, yes they had seen the Facebook pictures by then).

As the evening proceeded – the betrothed arrived, looking marvelous and happy, dancing while the Turkish band played both traditional and modern music. Copious amounts of beer, wine and Turkish rakı were consumed, which I found much more engrossing than information about the Byzantine-era cave graineries, which are still in use today. (Actually, the bride-to-be was the daughter of the owner of the Duru Bulgur, one of the biggest companies in Karaman.)

“Yes, all of that side of the family is extremely wealthy,” my wife Özge explained. “They are in the wheat business, in construction, real estate. Some own jewelry stores and pharmacies. They own most of this town. Alas, our family is probably the only one here that is not rich.”

“So we’re the poor relations?” I asked.

“Yes, exactly. We are the poor relations.”

I wondered what Henry James would have thought of all this.

The garcon brought another beer. Just then, the bride-to-be called, urging me to join her for a dance.

“Go ahead,” my wife said, laughing.

So I took a swig off the beer, got up and went to the dance floor. The owner of the hotel clapped me on the back. “Good, bacanak!” he said, and we all danced. Özge came, her mother, and even Vehbi, and many others came. We shouted, we spun, we whirled. We got our dervish on. We even dosy-doed at one point, if I remember correctly. We clapped our hands, we swayed and some nearly fell. Özge’s sister, after six glasses of rakı, eventually really fell down, but that was later, and that’s another story.

Sometime after midnight, most of the guest had left, including the charming betrothed. A handful of us were left, including the owner of the hotel. Glasses of rakı were brought. I was the only one who had cigarettes evidently, for I was pressed to share them and before long the whole pack was gone. It grew late, and Özge and I wanted to get home. Home was just a five-minute walk. Her sister had been unable to walk home, so her brother-in-law had got them a room at the hotel for the night.

“Let’s go,” my wife said.

“Yes.”

“Where are you going?” someone called. “Come and have soup with us,” they said.

“Soup, bacanak!”

“Soup! Soup!”

The hotel owner insisted. “Here in Karaman,” he declared, “We drink to the soup!”

I wondered if I was missing out on some manly ritual; that I would later be judged as not being up to the task (“The yabancı bacanak did not drink to the soup! This is, um, a distressing point.”)

“Sorry,” I said. “But tonight, I drink to the bed.”

My wife translated, and everyone laughed. I was off the hook, at least for the time being.

And so we went back to the apartment.

Everyone was already asleep, except her mother and grandmother, who had waited for us to return. We retired to the guest room, and where a bed had been made up.

“Drink to the soup,” Özge mused sleepily. “I’ve never heard that one before.”

“How is sister? Is she alright?” I asked.

“I think so. We’ll find out in the morning.”

“I’m glad we made this trip,” I said.

“Are you really?”

“Yes.” I was, too. Istanbul, with all its chaos and clamor and madness, was worlds away, and outside the prairie night slept under a cloud blanket that covered even the stars.

“Were you a whirling dervish? Did we dance all night? Did we drink to the …?”

She was asleep.

As it turned out, her sister was fine in the morning. Everything – and everybody – was fine in the morning.

All photos courtesy of the author.

James Tressler, a former Lost Coast resident, is a writer and teacher living in Istanbul.

This article is everything! I am moving to Konya in 6 Days and although I am going to based in Meram, just reading about Karaman is giving me goosebumps. I am in love with Turkish culture across the board and the opportunity to delve into the country’s quirks and intricacies is really exciting.

Thanks #TeamYabangee!!

Thanks Susannah! Iyi yolculuklar!