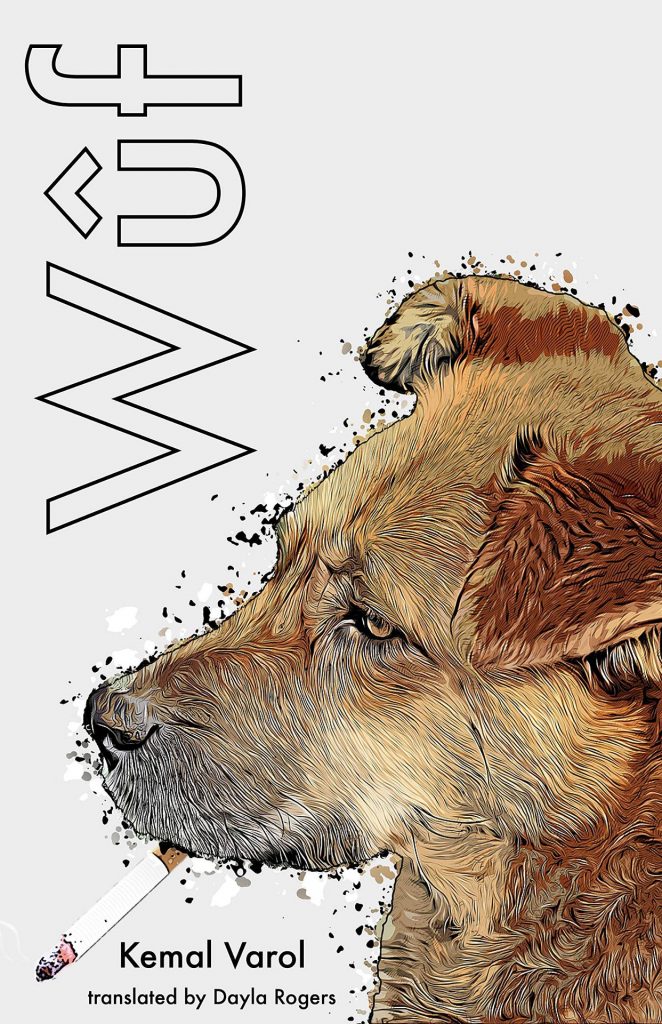

“Art is a lie that tells the truth.” This well-known phrase, attributed to Picasso in the early 1920s, takes up permanent residence in the mind of anyone who has learned to appreciate the tragedy of the literal mind. Some of the most real and affecting art has come to us through a veil of fiction in masterpieces like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun. Diyarbakır-native poet and author Kemal Varol’s novel, Wûf, is a worthy addition to this literary cannon.

Set in the 1990s in a fictionalized Anatolia, Wûf follows the uniquely tragic life of a pot-smoking, mine-sniffing dog whose destiny becomes bound up in forces beyond his comprehension and control: star-crossed love, war of every kind, sacrifice, identity, death, and deliverance. As his story progresses, both he and the reader attempt to navigate the senseless and volatile world that war engenders while desperately trying to retain notions of agency, dignity, and self-determination. By the end of the novel, you are left with a kind of dense emptiness that cuts through the politics and sloganeering of government-backed death and destruction, feelings that the very best pieces of anti-war literature do so well to inspire in us.

Yabangee recently had the pleasure to talk to Mr. Varol about his latest book. Check out the interview below.

Let’s start with the obvious—How did you come up with the fantastic idea to tell your story through the lens of a mine-sniffing dog who loves to smoke? What creative thoughts lead you to this decision?

“Great ideas,” to use your expression, sometimes emerge from necessity, from feeling stuck, and from having no other choice. For a long time, I wanted to tell the story of a painful event experienced in the country where I live, making myself the narrator. But I also wanted to tell a story that takes place not only in this country, but could take place anywhere that is divided along a line such as North and South. I also wanted to write the stories of people caught in the middle of a conflict, who are lonely, innocent, suffering, and condemned by everyone else. So, when I began writing my first draft, I noticed that my human characters voiced their own biases, and this made me quite uncomfortable. Maybe the easiest thing would have been to position people within their own truths, let them speak, and wait for a text to emerge from that. But it just wasn’t working. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t seem to get the results I wanted. Humans kept creeping into this or that part of the text and planting the flags of their ideas. Then one day, I saw him… at the entrance of a town, I saw a dog searching for mines along with some soldiers. At that moment, I decided to tell my story from the point of view of that dog. My dog hero was there. He was on duty with the soldiers. He was running his nose along the ground, but the presence of other dogs peeing at the roadside made him uncomfortable. Every now and then he pricked up his ears and listened to the howls of other dogs in the distance and then returned absently to his duties. It was clear that his mind was elsewhere. I wanted to write the story of this naïve, very romantic and unlucky dog.

The book centers around subjects that are politicized and sensitive in Turkey and throughout the world—terrorism, violence, the struggle for cultural and physical survival. How did you feel while writing about all of these? What did you feel you wanted to add to that conversation?

Nearly my entire life has been spent in close proximity to the issues that you have listed. I’ve always been saddened by being helpless to stop them. I’ve always been heartbroken by the glorification of violence and death, which are beyond healthy and reasonable thinking. In a way, this novel emerged as a result of this disappointment. It was written to tell the pain of people caught in the midst of conflict, who suffer both physically and psychologically, and to share their experiences. I wanted to write about the wounded, about those who were silenced forever through death, those who are afraid and suffering, those who were displaced, those whose bodies were in flag-draped coffins, those whose bones were found years later, those who were celebrated for heroism for a few days and then forgotten, and those who couldn’t tell their troubles to anyone. I’m not a politician. I never had such an ambition. I put everything through a literary filter. Literature has its own set of truths and these are always the priority for me. Still, I would like this novel at least to be read as the tale of the innocent.

The main character is written as having a “sad, tired face” that was the “result of a woeful tale that became all the heavier for lack of telling.” There are many histories and events in Turkey that aren’t widely known—Wûf feels like an attempt to tell one of those stories. Why do you feel it is important that people know about them?

Sometimes authors live with outsized dreams. We are attracted to the hope that we can change everything through writing and storytelling. In the end, we realize that we only have the power to leave a small question mark in people’s minds. Maybe this novel was written to generate that tiny question mark, that small doubt in the minds of readers who, all over the world, seek facts in the reports of biased newspapers and TV stations, submit to the dubious language of the media, who are uninformed about the things experienced in other parts of the world.

We see in the book how romantic love is affected by the great machine of war. Why did you want to focus on this in your story? What can we learn about war through love (and its destruction)?

Actually, more than love, I wanted to highlight the loss of innocence in the novel. Mikasa, the canine hero of the novel, is a big romantic. There’s no doubt about that. Throughout the book he watches the roads for his great love despite all his suffering and the loss of his legs. But with the approach of the war, he also senses the impossibility of being reunited with this love. This is the actual reason that he cannot genuinely reciprocate the feelings of the dog in the shelter who is in love with him. He doesn’t want to lose that innocence. That’s because war targets innocence first. Once that innocence is destroyed, everything is very easy for the war.

One of my favorite moments in the book is when a soldier who forms a bond with our protagonist has a kind of breakdown. Absurdly drunk, he laments:

“Life,” he said. Wake up, son. Women. Mother fuck. Dawn, the sea, tokens, booze, Afghani weed, Galatasaray, the cup, crosswords, […] the South, the war, the days. Mother fuck.”

It comes off as endearingly sad and painfully comedic. Everyone is overwhelmed with war—they’ve had enough of it and they barely seem to understand it. Do you feel this reflects how Turkish society feels about war?

I also really like that scene when Mami leaves everything behind, his head is swimming, and he’s torn to a thousand pieces. Please remember Tim O’Brien’s novel “The Things They Carried”, which I really love. In that novel, you’ll see a good example of how Vietnam syndrome affected people, what kinds of effects linger in soldiers who return to everyday life, how the claims that sent them to war are invalidated over time, and they are left all alone with their memories. I think more so than society’s feelings about war, that scene shows the thoughts of a soldier who has been subjected to the horrific effects of war and is quite lonely, desperate and in pain. This is not an issue particular to Turkish society. Broad groups of people everywhere live with that same feeling. I think I wanted to represent that the pain is sometimes veiled with patriotism and sometimes with the help of a grand ideology. In a way, I also wanted to show those who talk big about war the huge price, the irreparable wounds made in people’s internal worlds. Of course, this is not something that broad masses of people are going to understand. So, maybe it’s necessary to ask about that pain to those who have paid the price, who are forced to live with psychological and physical scars.

The book is also a tale of personal vengeance and the triumph (although at great cost) of the individual. It is an affirmation of existence and rebellion in a world that forces people’s stories and roles into black-and-white, binary categories. Do you feel it’s important to remind people of the primacy of the person over the crowd? What do we lose when individuality is erased?

I’d just like to note that the book is a tale of unsuccessful personal revenge. We know definitively whether or not Mikasa reaches his goal. In fact, Mikasa is also guilty of reluctantly causing the deaths and injuries of the soldiers. Unfortunately, societies do not listen to one another. Group actions do not only erase individuality, but also conscience and truth. Therefore, we have to sit and listen to one another’s stories in order to avoid losing even more and becoming inhuman. We need to understand one another. Otherwise, this reckless collective spirit will suck us in and destroy us.

The book avoids referencing the actual names of people and places that would be more widely known. This has the wonderful benefit of removing the most bent political lenses when considering the story and allows it to exist on its own terms. However, some people might say this is an abdication of responsibility, that we should be honest and direct about who is “right” and who is “wrong” in such conflicts. How do you respond to such an idea?

This is a method that I chose both as an author and also as a matter of conscience. In Wûf, I could have produced a novel that was easy for me to write by openly stating everyone’s name categorizing everyone according to their position. But I doubt it would have been a good piece of literature. Good thing I didn’t do it that way. Otherwise, there would have been this sense of realism, which would have made me uncomfortable. I am a writer who seeks the truth within imagination. I always try to pull reality to a tolerable middle ground in which I can break it down and show its various faces. I have these kinds of concerns all the time while writing. I live with thousands of worries. Who knows, maybe these kinds of worries have given me a kind of “narrative anxiety.” On the other hand, I hope that by carrying the place and characters of the novel to a broader stage, this novel will be able to meet with similar stories from all over the world. If I had pinned them to places and names that are well known, I wouldn’t have had this opportunity. This choice made writing the book more comfortable and enjoyable., as I mentioned above. While writing a novel, it’s not about who’s right and who’s wrong. The author shouldn’t be concerned about that. I am more concerned with relating suffering that doesn’t square with people’s grand statements.

The book ends on an emotionally dense note which resonates quite deeply within the reader, but there are hints of the future included as well. Is there a potential sequel to the book? Is there more that these characters and their children can tell us?

I am generally not turned on by the idea of writing a sequel to a novel. Instead, I do this: I love to use explicit and implicit references to tie my books together and give the sense that I’m writing the pieces of one, big novel. I told the story of Mikasa’s grandfather in my first novel. In the novel that follows Wûf, I had Mikasa’s grandkids running here and there in the streets. I use this technique rather than writing the sequel to a specific novel. I’ve always enjoyed this technique, which is known as, “self-intertextuality.” But to answer your question: Maybe like in the end of the novel, when there really is peace, when we realize that all of the things we’ve experienced are just a painful fairy tale, one day I’ll tell our real stories—the ones of the things we’ve left behind, our dead and those who’ve suffered fates worse than death.

Kemal Varol’s Wûf is available as an e-book via Amazon, with a physical copy most easily obtained via the University of Texas.