It is almost a cliché to say that behind every name in Istanbul there is a story; nevertheless, the saying is true.

For instance, I work on Şaşkınbakkal, which is located in Suadiye and intersects Bağdat Caddesi, the famous shopping avenue. In ancient times Bağdat Caddesi was part of the trading route that led to Baghdad, hence the name.

At first, the name Şaşkinbakkal had no special significance for me. Then one night, a Turkish friend shared a classic Turkish rock song, “Şaşkın,” by Erkin Koray. He explained that the word şaşkın meant “confused.”

I was curious (or you could even say bewildered) as to why the street would have such a name. Later I found out that in the days when the Asian side was still mostly uninhabited, except for a few summer houses, a man set up a bakkal, or grocery store. To the very few people living there at the time, it seemed an odd endeavor: to open a shop where hardly anybody lived.

“Are you confused, kanka?” they asked. And so the memory of this “Şaşkınbakkal,” or “Confused Grocer” stuck in people’s minds, and he lives on in the street which bears his name, or his story at least.

****

Behind every street name there’s a story… This thought inspired me to embark on a survey – admittedly haphazard – of some other streets in the city that might also invite speculation. It was a romantic idea; I imagined writing a series of interconnecting stories based on the legends behind the names of Istanbul streets. They could be wrapped together under a title, something like “Back Streets, Back Stories,” or “Avenues of Nostalgia,” or whatever preposterous nonsense my 40-year-old, over-Americanized imagination could produce.

I’m not sure if I have the time or energy to actually pursue this project. But just for the sake of discussion, let’s take a quick look and see what we’ve got.

****

Now, I know some readers will have some streets already in mind: Fransız Sokağı, “French Street,” which honors the French legacy in Istanbul, or even Zürafa Sokak, “Giraffe Street,” historic home to the city’s brothels. But these are obvious choices; as always, I am interested more in things out of the immediate range of focus.

In some cases, I suppose, the names of districts or neighborhoods could serve our purpose. Take Ayrılıkçesme, or “Separation Point,” which readers living on the Asian side may recognize as the metro station near the Nautilus shopping center and now connects to the Marmaray metro.

In Ottoman times, Ayrılıkçesme was also a departure point, the place where pilgrims would say good bye to their families before embarking for Mecca. The word çesme means “fountain” in Turkish, and so I’m guessing there must have been a fountain somewhere nearby.

Or consider: Selamsız, a neighborhood in Üsküdar. Selamsız means, “without giving a ‘selam,’ or greeting.” According to local lore, this area was named after a local sheikh who was known for never saying hello to anyone in the street. So basically, the area was named after a rude sheikh. Rude Sheikh: that almost sounds like a good band name!

Speaking of Üsküdar, a friend with whom I’ve just been discussing this story suggests Delikoç Sokak, or “The Mad Ram Street.” The Mad Ram! I wonder what happened there. Did a ram one day suddenly go insane and start rampaging down the street, battering houses and horse carts and generally terrorizing the citizens of Üsküdar? It’s an image worthy of contemplation.

Or what about Yanık Mektep Sokak? “The Burnt School Street.” I think we can all guess what happened there. Or can we? Did it involve arson? Was there an errant bolt of lightening, or was a more prosaic fallen candle to blame?

Other names are plain misty, evocative — like, Mütfü Kuyusu Sokak, “Well of the Preacher Street.” That name just has a certain poetic resonance, doesn’t it? I wouldn’t mind taking that for a book title. Perhaps it would make a good setting for a story about a man – a rude sheikh perhaps – seeking some form of absolution. The Burnt School Street could be thrown in for a bit of symbolism.

Let us string these names together, just for size. Imagine you were invited to attend a party in Üsküdar. You enquire how to get there.

“Easy,” the friend says. “First, find Rude Sheikh Street, turn left on Mad Ram, go past Burnt School and finally you will arrive at the Well of the Preacher.”

****

You’ll have noticed by now that I’ve confined my survey to the Asian side of the city. Well, that’s where I live, work and spend most of my time. Surely the European side is not without its own share of storied noms de rues.

But just in passing, I’d like to point out one of my own favorites. Yüksek Kaldırım Caddesi in Karaköy. It means “The High Pavement Street.” You’ll have likely taken it, a steep, picturesque street that leads up the hill to the Galata Tower. With its daunting steps and rows of old buildings looking down from all sides, it could have been an excellent location for a Hitchcock thriller, especially on a grey, foggy afternoon or at night.

Most of these names came just from a quick survey of the map. Imagine how many more strangely named streets are out there, with their own histories and legends. If you know of any interesting street names in your neck of the city, feel free to pass them along.

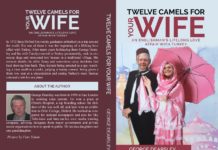

James Tressler is the author of “Conversations in Prague,” and “The Trumpet Fisherman and Other Istanbul Sketches.” He lives in Chalcedon.

What are Letters from Istanbul?

Istanbul is a million villages woven, one might even say, thrown together, rather than a single vast city. The city is best understood by understanding little bits at a time, one person at a time. It is a city that defies perspective, for it is constantly shifting. It is an endless parade of street musicians playing simple, overlapping melodies, rather than a symphony orchestra striking a single majestic chord; it is an intricate mosaic rather than a grand oil portrait, the pieces of the mosaic each giving meaning and sustenance to the whole.

All that sounds a bit high-flown, I know. But to paraphrase James Joyce, the universal lies within the particular. So, that’s the intent of these Letters: to gather up those mosaic tiles one at a time, and to find the little stories that fall between the cracks. Hopefully the pieces of that mosaic will add up to an interesting portrait of this city a lot of us call home.

I’d purchase a noms de rue livre.

Yes, the romance disappears from a language as you learn it. I remember going through this process in Madrid, when I understood that the metro stop of Lavapies simply meant ‘wash feet,’ for example

[…] note: Last week, I wrote about the stories behind some of Istanbul’s street names, and the week before that I traced some of Kadıköy’s history back to its origins as Chalcedon. […]

I was researching a bit on the street names of Istanbul and stumbled here! Thank you for sharing the information.