Ali was a 27-year-old Kurd from the eastern Turkish city of Van. He and his brothers had come to Istanbul nearly a decade before and started up a taxi business. They drove standard yellow taxis, but in private they referred to themselves as owners of the Lahmacun Taxi Co., a nod to their hopes of opening a restaurant someday.

Ali, the youngest of the brothers, didn’t like being a driver, especially in Istanbul. The traffic was too bad. He hated Thursday mornings the most, when he had to pick up an important regular client who lived near Üsküdar on the Asian side, and shuttle him over the bridge to a business meeting in Levent. The bridge traffic was a nightmare, and it meant he had to get up very early to even hope of getting any kind of jump on it.

In a city like Istanbul, fifteen minutes either way in the morning can make a big difference. If he picked up the client on time, promptly at seven o’clock, then the trip wasn’t too bad. But if he was even a few minutes late (occasionally either he or even the client overslept), then the normally thirty-minute trip could take well over an hour.

This morning he had gotten off to an early start, though, leaving the flat at half past six, and everything was running on time. He was driving through the streets of Üsküdar, which were still pretty quiet at that hour. On the radio, he listened to Kurdish pop music, occasionally switching over to listen to the news about the fighting in Kobane. There was also some commentary about some recent remarks by the president, who had reportedly said that Turkey did not have “a Kurdish problem,” that Kurds had equal rights as Turkish citizens.

The president pointed out that Kurds had been elected to high government posts, and that the government had worked hard to develop the south eastern part of the country.

“For God’s sake, what is it you don’t have that we have?” the president reportedly asked. “You have everything!”

The commentators were discussing the speech, and one of them was saying, “If there is no Kurdish problem, then why has the president declined to meet with rebel groups?”

Ali flipped the channel back to the Kurdish music, humming along as he continued driving. He stopped outside a café and looked inside. The proprietors knew him and were expecting him, for a young boy came outside with a bag containing a simit, and also holding a paper cup of fresh, hot tea.

“Sağol, genç,” Ali said, taking the bag and coffee, and handing the boy a few coins. He checked the time. There was enough time for him to park near the client’s flat and enjoy his breakfast.

“Pardon? Are you available?” A voice interrupted his thoughts. It was a young Turkish man, accompanied by a woman. “We need to get to a hospital in Şişli. We have an appointment this morning and really need to get there.”

“Maalesef,” Ali said, shaking his head. He explained that he was waiting for his client.

The couple looked desperate, and appeared not to have heard his answer.

“We really need to get there,” the man explained, speaking quickly. The woman appeared in a haze, as if she were barely awake. “We can pay you something extra.”

“There are other taxis, abi,” Ali said, with some irritation. He hated having his breakfast interrupted. It was one of the rare moments of the day he had entirely to himself. He waved the young man off.

“Here is fifty lira,” the young man said insistently, waving the money in Ali’s face. “That’s a tip if you’ll just take us. Seriously, we really need to get there. We have a special early morning appointment, and it’s really urgent.”

At that precise moment, the client appeared. He was dressed conservatively in a dark business suit and was freshly shaved, alert. He greeted Ali pleasantly, and surveyed the couple. After some conversation, in which the situation was discussed, debated, it was agreed that the couple could share the cab.

“No problem, no problem,” the client said. He was actually a fairly generous, easy-going fellow. After all, he said, it wasn’t that big a deal. Ali could drop him in Levent first, then take the couple to the hospital. It was still early, and barring any accidents, the traffic wouldn’t be that bad.

“Tamam,” Ali said, inviting the couple to sit in the backseat with the client. But the client, always considerate, said he would sit up in the front seat with Ali, and the couple took the back seat. He had turned down the radio to talk to the couple. Now, with the client in the car, he switched the channel to traditional Turkish music, and starting up the engine, he put the remainder of his simit in the bag. He would finish it later.

“Afiyet olsun,” the client said.

“Sağol, hoca,” Ali said, addressing the client respectfully. He glanced in the rear-view mirror. The couple was sitting pensively in the back seat. The man was looking worried about something, while the woman stared blankly out at the passing buildings.

They hit traffic at Capitol, where the Europe-bound cars need to take the bridge exit. Fortunately, since they were coming from Üsküdar, their wait wasn’t that long. The drivers coming from the eastern outskirts were jammed back several kilometers.

Ali skillfully weaved back and forth between lanes, getting a feel for which lanes were moving and which ones were stuck. A bus thrust its way across the lane in front of him, forcing Ali to wait. On the left, a motorcyclist whizzed past, snaking around the cars.

“Manyak,” the client huffed after the motorcyclist. He turned and politely addressed the young couple.

“Is everything alright?” the client asked, glancing with polite concern at the woman, who was still looking out the window. Earlier, the couple had told him that they were going to the doctor.

“Yes, hoca,” the young man said. “It’s just the usual woman’s problem.”

“Ah, I see,” the client said, with feeling. “Geçmis olsun.”

“Teşekkür ederiz, hoca,” the young man said.

“Sağol,” the woman whispered, forcing a smile.

“Yes, it is a normal, natural thing,” the client said. “Of course, in the end, family is the most important thing in life. Our family is really all we have. And, trust me, young man, you cannot really be happy until you start a family, have children. Me, I have three daughters and one son. The girls are all married now and have their own families. Our son still hasn’t settled down, but he will. He just needs time. So I take it you’re married?”

“Yes, hoca,” the young man said, his eyes inviting the elder man to see the wedding ring on his right hand. He put an arm around the woman, and tried to raise her hand too, but the woman kept the hand in her pocket. She twisted her face into a smile. “Sorry,” she said, addressing the patron. “I’m just not really a morning person.”

“It’s OK, kızım,” the patron said, with his typical magnanimity. “You should take it easy. So when are you expecting?”

The couple exchanged a glance.

“Summer,” the young man said.

“Ah, so you have time,” the patron said.

Meanwhile, the driver Ali wasn’t really listening. Once, he looked in the rear view mirror and noticed one of the button’s on the young man’s jacket was carelessly unbuttoned. The young woman’s face was pensive, inscrutable behind a pair of sunglasses.

They had made it to the bridge, and the traffic was moving fairly steadily. Over the city hills, a fog had enveloped the horizon. Far below, ships in the gun-metal gray Bosphorus were passing on their way northbound to the Black Sea; tomorrow they would be heading south to the Marmara Sea, en route to the Dardanelles and the Mediterranean. Here, on any given day, the crowded world drifted urgently past, colliding and converging.

One day, he would be through with all this traffic, he thought. He and his brothers would have enough money for the restaurant. They already knew of a property in Kartal that was reasonable. The rents in the center of the city were too high, but Kartal was still pretty affordable. There they could have the shop and they would never have to deal with the traffic again, except maybe to do deliveries. But they could hire a boy to do that.

After all, he and the brothers had been driving for nearly ten years now. There had to be some kind of seniority somewhere in this life. Like the patron sitting next to him. The patron had proudly told him of how his family had come to Istanbul from a small town near the Black Sea, all of them builders, and now they had a successful construction company in Istanbul. It had taken a generation or two, but they had done it.

“You can do anything, my son,” the patron liked to say. He called Ali “son,” in the manner of a mentor. “In this world, you can do anything, as long as you put your mind to it and work hard. Of course, we also need a bit of luck, and God’s blessing. But remember that, you can do anything in this world, my son.”

When they crossed the bridge, they continued along the highway. The traffic wasn’t too bad, and in a matter of minutes they were in the business district of Levent. It was about a quarter to eight. Ali dropped the patron off at the office building. The patron handed Ali the money, thanked him and got out. He also wished the couple well, and with a kind of jerky wave, disappeared into the glass building.

“What time is your appointment?” Ali asked.

“8:30,” the young man said. “We’ve got time, as long as the traffic isn’t too bad.”

“I think you’ll make it,” Ali said. They had mentioned a hospital, but hadn’t told him the name. He asked the couple.

“Actually it’s not a hospital,” the young man said. “It’s a clinic. It’s near –” Not exactly sure himself, the young man got out his smart phone. Finding the address, he showed it to Ali. This important detail cleared up, they started their journey.

A short time later, they were near Şişli, Ali navigating the steep, narrow, traffic-choked streets. There was some kind of construction going on, so he steered the car down an alleyway and out onto an adjoining road, where the traffic was just as bad.

“We’re not going to make it,” the woman in the back seat was saying.

“We will, aşkım” the young man reassured her. “We’re almost there now.”

“You’re sure that this is what you want?” the woman asked.

“Aşkım, we’ve already been over this a million times,” the man said. “It’s the best thing for us at the moment. You know, the timing isn’t right.”

“I know,” the woman said. “But you know… what if this could be my last chance, my only chance?”

“No, no,” the young man said. “We’ve got time. We’ll get married first, and then we’ll try again.”

“When?”

“Next year. Next year, for sure.”

“So my friend says this doctor is very discreet,” the woman said, after a moment. “He doesn’t give a lecture, and he doesn’t keep records of it.”

“That’s good,” the young man said. “That’s what we were worried most about – other than you, your health, of course. We worried about them notifying your work, or your parents.”

“Yes,” the woman said. She seemed to be more composed now. “My friend says he is very discreet.”

“Good,” the young man said.

Up front, Ali wasn’t really listening. He had switched the radio back over to the Kurdish pop channel. He hummed along to the melody, tapped his hand to the beat. He wasn’t feeling that great – he was trying to will himself into a good mood. It still bothered him, having his breakfast interrupted. Well, maybe after he dropped the couple off, he could pull over, finish the simit and have a quick nap.

It was nearly a quarter past eight. He would have to step on it a little if they were going to reach the clinic on time. He could sense the couple’s growing urgency in the back, and it irked him. Everybody in this damn city was always in a hurry; everybody always had to be somewhere. Hadi! Hadi!

Suddenly, he had a vision: lahmacuns falling from the sky. It was a blurry vision, of the Turkish pizzas, little lahmacuns falling from a gauzy and lyrical sky. Seized by this lahmacun vision, Ali imagined he was pursuing them, swerving in and out of the lane, honking his horn, attempting to pass the other cars, whose drivers honked and yelled back.

“Lahmacun!” he cried, stepping on the gas, swerving around a car, passing another.

“Lahmacun! Lahmacun!”

“What are you on about, şoför bey?” asked the young man in the back seat. “Are you hungry or something? Didn’t you eat breakfast?”

“Lahmacun! Lahmacun!” Ali cried, ignoring the questions. He went even faster, miraculously swerving around the other cars, braking suddenly, accelerating.

“Slow down,” the young man said. “You don’t need to kill us!”

“Lahmacun! Lahmacun!”

“This guy’s a nutcase,” the young man whispered. He needed a cigarette badly, but on the dashboard of the taxi in front, there was a “No Smoking” sign. He would have to wait.

A few minutes later, they arrived at an intersection at the top of a hill in Şişli.

“Are we there?” the young man asked.

Ali pointed to the left. “It’s that way, a couple of blocks,” he said. “I can’t take the car that way.”

“A couple of blocks? Tamam,” the young man said. “How much is it?”

“Just ten lira,” Ali said. “The hoca paid for the journey from Üsküdar.”

The young man handed a ten-lira note to Ali, and started to give him the fifty as promised.

“Don’t worry about it,” Ali said, waving the young man off.

“I insist,” the young man said, but Ali still refused, relenting only when the young man put it on the dashboard and hurried out, his companion following him.

“Geçmiş olsun,” he added, addressing the young woman.

“Teşekkürler,” the woman said.

Outside, they checked the building number to see if they had the right address.

“Lahmacuns!” the young man grumbled bewilderedly. “I still don’t know what that driver was on about!”

But the young woman wasn’t listening to him. Taking a deep breath, she was getting ready to go inside.

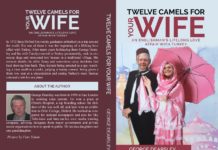

James Tressler is a writer and teacher whose books, including “Conversations in Prague,” and “The Trumpet Fisherman and Other Istanbul Sketches,” can be found at Lulu.com. He lives in Istanbul.

Featured Image Source: Iker Merodio | CC BY-SA 2.0 | Flickr

James,

Your letter about 27-year-old Ali was wonderful. You took a serious subject and made it the shadow piece of what appeared to be a piece about a Turkish cabbie trying to get through the day and the traffic and grumbling about his breakfast. Reminded me of spending two days in Istanbul with a Turk who took me on a birding tour. The first day we took bus, train, boat. The second day he drove his car. Halfway through the day he asked if I wanted to drive. I have never answered any question faster. “NO!”

[…] I set about looking for stories that could be classified as “scherzos.” The first one, “Lahmacuns in the Sky,” was about a Turkish couple’s adventures with a crazy taxi driver while en route to a private […]