In a continuation of my conversation with Matt Loftin, Utku Öğüt, Alper Erkut, Gabriel Clark and Paul Osterlund of Sonikraf, we discuss the history of the independent music scene in Istanbul.

You’ve all talked a lot about the venue Peyote. Could you explain its importance for independent music in Istanbul?

Utku: I used to hear about this venue because Rashit, one of the first punk bands in Turkey, were playing there. Mor ve Ötesi used to play there also. This place was opened by Hakan Orman, who was a really cool guy.

Gabriel: Yeah, he gave us our first gig. When we gave him a demo he said, “Look I’m going to listen to your demo and the only thing I’m interested in is if you enjoy playing the music. If I can hear that you’re enjoying playing, then that’s what qualifies you to play here.”

Utku: At our last concert, the final song was dedicated to Hakan Orman. He’s the unsung hero of the Turkish independent music scene. He first opened the bar because back in the ’90s and early 2000s, only bands playing covers could take the stage. He was the first guy ever to get bands playing their own songs. Back in 2005, Peyote got really famous and lots of bands applied to play there. He had one requirement: no covers. Just play your own songs.

I met him when I was 19 years old. I was tired of searching for a venue to play at. Our drummer had left so we had to play with a drum machine. It was kind of electro punk stuff and it sounded awful. I gave him this demo tape but wasn’t expecting a gig. Then, he called me and said “You’re playing on Saturday.”

The generation born around 1985 grew up with Hakan Orman. He wasn’t interested in performing music or producing music. He was just a cool listener with good intentions. Without commercializing. He made money from drinks and so on. He was just giving the bands a chance to play and express themselves.

If we played really bad, he would call us over after the gig and ask, “What are you doing, son? If you needed more alcohol during the set, you should have asked.” (laughs) He always motivated us with criticism.

Lots of my friends were playing in a band, and they wanted to take the stage at Peyote. But Hakan trusted his instincts and could sense if a band saw Peyote a step to fame. He never invited them. They eventually became famous, but never played in Peyote.

Gabriel: It was an oasis in Istanbul at the time. It’s still kind of like that, but was more so 10 or 15 years ago when every bar and every club were just doing cover bands. The idea of an original music scene was really unusual.

Utku: In Peyote, the policy was that there were some tickets sold at the entrance and that all the money from tickets went directly to the band. But sometime there weren’t many people at the show, so there were no tickets sales. So, he would announce the concert in other floors and made the entrance free so that people could at least hear the band. He did this once for me and as we were packing up he asked if we had money for the taxi. We said yes although we didn’t. He cared about us. He was like a real abi.

On June 15, 2011, he passed away and I cried by his grave. I visit his grave in Emirgan Cemetery every year on the anniversary of his death. He was a brother to me.

How easy was it to get ahold of independent music in Turkey during the ‘90s and early 2000s?

Utku: Broadband came to Turkey very late—around 2003 or 2004.

Gabriel: What was happening before that?

Utku: There was Akmar passage. If you go there, you will find lots of bookstores but back in 1999 it was all music and t-shirt stores. And they were selling albums. For example, there was a store called Saadeth music.

Paul: It’s funny that it’s called “Saadet” [the religious term for happiness].

Utku: Not Saadet, SaaDETH.

Matt: Was it like these DVD stores where they would sell lots of copies of things?

Utku: Yeah, exactly. There were some guys who were buying original music from other countries and copying it. We were just pirating everything. If there had been original records, we would have bought them but there weren’t any.

Also, they were just ordering stuff from foreign countries separately—not in bulk—so the taxes were higher. So, metal and punk cassettes were more expensive than a Serdar Ortaç CD, a Korn CD or a Metallica CD.

There was a dial up connection provided by the state and it was so slow. It took one or two hours to download an album but you wouldn’t want to sit and listen to it at your computer. So, you had to connect the output of the computer into the input of the tape recorder to copy all of it onto a cassette (laughs). I have a big collection of “Sisters of Mercy” albums ripped directly from the Internet onto cassettes.

You mentioned that the advent of the high-speed Internet brought copyright laws to Turkey, as well. Why didn’t they exist before that?

Utku: Because of the coup in the 1980s, there were just arrangements of Western songs with Turkish lyrics. In the ’90s original compositions emerged and everyone loved it. Everyday a new pop star was announced in the mainstream news on TV. Back then, television was owned by the state, by the way. There were just two or three labels that controlled the industry. Everyone could get pop albums everywhere—even in gas stations or bakkals. There were even promotions in which newspapers gave away pop albums.

So, Turks weren’t home taping because pop albums were so cheap. The home taping was limited to the people listening to Western, underground music. So, we didn’t need copyright laws until licensed copies of that Western music became more available.

Are there any artists from Turkey that you really connect with? What do you think of styles that blend Turkish elements and Western music?

Paul: The first musician I really latched onto was Selda Bağcan. Her self-titled album still blows my mind. You had a female solo artist playing guitar, which was unheard of in Turkey in 1971. She had an incredible band behind her playing electric saz. When I first lived here in 2008, all my friends were making fun of me because they were all listening to Western music.

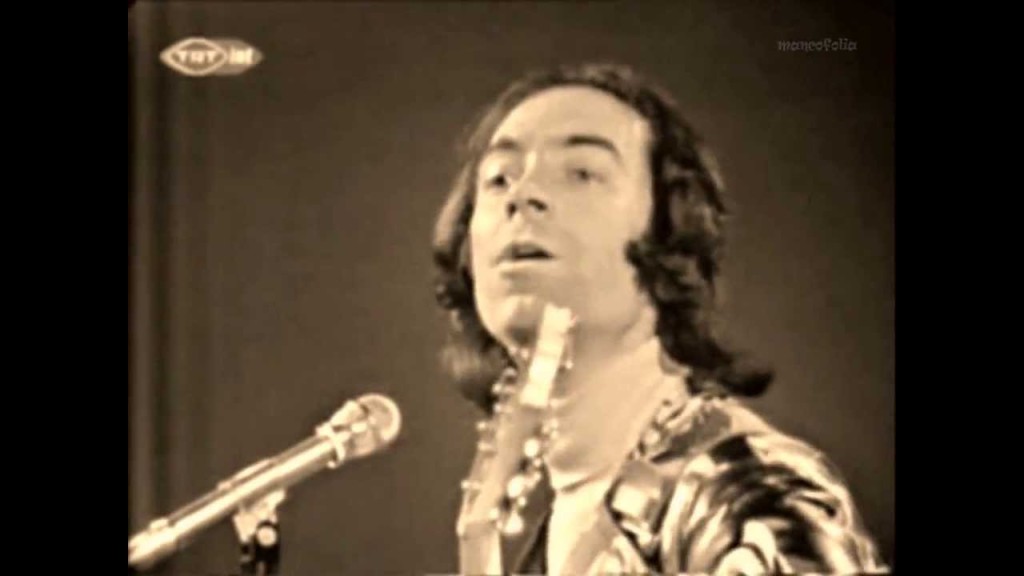

Utku: There’s nothing to make fun of. Let me explain: There’s two aspects of Turkish folkloric stuff combined with a Westernized style. First of all, the original Anatolian rock, which is the first generation, did it very sincerely. For example, Cem Karaca or Erkin Koray visited the real “aşık”s,or Turkish bards, in their own villages and tried to learn original forms—very orthodox forms. They tried to learn all these musical elements in their own context. They really captured the soul of our folkloric music and combined it with rock.

But after the military coup in 1980, this connection between my generation and the old generation was broken. And then in the ’90s, Anatolian rock was reinvented.

Could you talk more about the military coup?

Paul: A lot of people would argue that understanding the Turkish scene today and the condition of cultural movements in general is not possible without understanding the 1980 military coup. It’s the reason why the music scene today is not as productive as it could be.

Utku: Yeah, it was an interruption in the evolution.

Paul: A major interruption. If you’re talking about anything cultural in Turkey, it has to be related to the military coup in the ’80s. People like to say that Turkey is 10 years too late. It’s because of the military coup. Think about it: In 1980 in America or Europe, punk was flourishing. It was blowing up, but in Turkey there was a curfew.

Utku: If you look at the musical history of Turkey, either pop or rock, there is a lot of discussion about the repertoire from the ’60s to the ’80s. But no one talks about what happened during the ’80s because that part of history is missing.

Paul: For example, punk emerged in America and Europe in the late ‘70s but the first punk group in Istanbul was the Headbangers in 1987. That means it was 10 years behind. There were punks in Turkey in the 1980s but those guys got beat up by the cops.

There’s a book called Türkiye’de Punk ve Yeraltı Kaynaklarının Kesintili Tarihi (An Interrupted History of Punk and Underground Resources in Turkey). It’s out of print but the website still has really important excerpts from the book that discuss these ideas and features lots of cool photos from the early ’90s. This guy Tolga Güldallı, one of the writers of the book, is in his forties and he’s played in punk bands for more than 20 years.

When was the curfew lifted?

Paul: Three years later in 1983.

Utku: But the people were traumatized. One generation didn’t produce anything influential. As a result, in the ’90s and 2000s we had to create a new rock culture. This new rock culture used electric guitars, drums, bass guitars and even distortion pedals. You can play “Rock” with this arrangement but you can’t necessarily play “Rock ‘n’ Roll”. There’s a big difference. All this stuff written after the ’80s wasn’t Rock ‘n’ Roll. It was just Rock. It was Rock n Roll without sex and drugs, stripped of all its evil.

Matt: Stripped of its primal-ness.

In the USA, the rock and hip-hop scenes are infamously segregated along racial lines. How is it in Istanbul?

Matt: I’m always running into new scenes in Istanbul. I’ve just found out there’s a vibrant hip-hop scene in Istanbul that I had no idea about. I think there is a lot of mixing.

Paul: I don’t think segregation is an issue. I think in Istanbul if you want to do something, it’s just like “Go for it.”

You can read Part 1 of this interview here.

Utku Öğüt has been playing in many kinds of bands around Istanbul for years. His main project at the moment is Kutu.

Alper Erkut is a musician and promotor. He is involved in several bands including Foton Kuşağı and Indefinite Time Period. He also runs the record label Byzantion Records and the music collective Tight Aggressive.

Matt Loftin is the lead organizer of Sonikraf. He plays bass and is also involved in the bands Kutu and Foton Kuşağı. He hosts a radio program on Thursdays at 20:00 on StandartFM.

Gabriel Clark has been here since 2004. He’s an English teacher and has been active in the music scene here since he arrived with his projecst Chorni, Camphor, and his old project Pis Yabanci.

Paul Osterlund has lived in Istanbul for over four years. He is a journalist/writer and plays in Foton Kuşağı and Ferforje. He loves to wander the city alone.

[…] Our good friends at Sonikraf have just announced the release of their debut compilation A Day in the Park, featuring 15 underground artists currently based in Turkey. To support their efforts in growing the local music scene, listeners can opt to donate whatever amount they’d like in exchange for the Sonikraf compilation. For those unfamiliar with the important work being done, check out last year’s interview with the Sonikraf team. […]