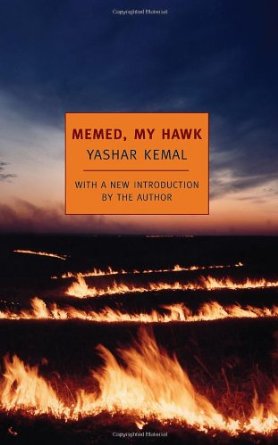

Before Orhan Pamuk came to prominence in the West and launched Turkey once more into the international literary scene, Yaşar Kemal was Turkey’s best-known writer, nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature several times since 1973. A Turkish writer of Kurdish origin, he has been compared by many to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. He is known for combining the folk stories and legends of the Çukurova plain of southern Turkey with the Turkish vernacular of the region, thus recreating the Turkish that was spoken by Turks before the purification of Turkish by Atatürk. This was possibly motivated by his love of the culture that sustained him and made him the man he was; a Gramscian ‘organic’ intellectual giving a voice to the masses, who were removed from the West-oriented version of Turkish culture that was dominant in the big cities of western Turkey. He was proud of his culture and wanted to offer it to the rest of Turkey, possibly the world.

Before Orhan Pamuk came to prominence in the West and launched Turkey once more into the international literary scene, Yaşar Kemal was Turkey’s best-known writer, nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature several times since 1973. A Turkish writer of Kurdish origin, he has been compared by many to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. He is known for combining the folk stories and legends of the Çukurova plain of southern Turkey with the Turkish vernacular of the region, thus recreating the Turkish that was spoken by Turks before the purification of Turkish by Atatürk. This was possibly motivated by his love of the culture that sustained him and made him the man he was; a Gramscian ‘organic’ intellectual giving a voice to the masses, who were removed from the West-oriented version of Turkish culture that was dominant in the big cities of western Turkey. He was proud of his culture and wanted to offer it to the rest of Turkey, possibly the world.

The region of Çukurova, which is made up of Osmaniye, Mersin, Adana, and Hatay in Southern Turkey, was a geographically rich and fertile land at the time of Kemal’s youth. Its folk culture was also rich in stories and legends. As a young working man living in the south of Turkey, Kemal would go on to collect and write the folk tales that had been passed on through the oral storytelling tradition, one of which was the legend of İnce Memed (“Slim Memed”). The story was published as his debut novel in 1955 and became the first in Kemal’s İnce Memed trilogy. Translated into many languages, the book is known in English as Memed, My Hawk. It was the story that propelled Kemal to international fame and inched him closer to the Nobel Prize.

In the novel, Memed is a boy who lives in a village in Çukurova plain with his mother Deuneh. Unfortunately for them and the vast majority of their fellow villagers, they are grossly mistreated by their cruel feudal landlord Abdi Agha. Memed, being a poor and wronged farmer living with his widowed mother can’t help but feel anger at the despotic Agha who has too much power over the poor peasants. The final straw is when his beloved Hatche is unwillingly promised to Abdi Agha’s nephew. The two young lovers then run away from the village, only to be tracked down by the Agha. In the resulting conflict, Memed kills the nephew and injures the Agha. Knowing that he faces imprisonment, Memed leaves behind his beloved and runs away to the mountains where he takes refuge with an old man called Süleyman. Süleyman takes him to join Mad Durdu’s band of eşkiya or bandits who live outside of society and rob travelers in order to survive. Without intending to, Memed becomes a Robin Hood-like hero whose aim is to steal from the rich and give to the poor in order to restore justice.

The story flows in a way that is at once folkloric and realistic. Even though Slim Memed is a character whose bravery makes him legendary and his story is epic in nature, you sense that he is a three-dimensional character and a real person who is under a lot of pressure to fulfill peoples’ expectations of him. Through a series of events, he has become an outlaw and a hero for the downtrodden peasants of his village, a role which burdens him because he is tired of the outlaw way of life. This struggle is shown in Hatche’s mother’s half-plea and half-curse:

“Are you going to give yourself up? Coward! This year for once Dikenli plateau has not gone hungry. For once we’ve eaten our fill. Will you let Abdi Agha swoop down upon us again? Where are you going, you woman-hearted Memed? To surrender?”

But on the other hand, Memed has a chance to accept the authority of Abdi Agha and disregard the needs of the peasants if he surrenders to the amnesty. This would mean he would have land of his own with a house and fields and be able to show his face in society. But instead, he sacrifices his personal needs once again and does what the village wants him to do because he is now too identified with the image of himself as an outlaw hero. When he refuses to surrender and at long last kills Abdi Agha, he bitterly turns towards Hatche’s mother and says “Mother Hürü… It’s done. Now you have no more claims on me!”

The internal dilemmas that Memed faces partly mirror those faced by Yaşar Kemal in his own life. Like Slim Memed, Kemal was also left to take care of his mother after his father was killed by Kemal’s adopted brother. His mother was disappointed when he refused to kill his adopted brother to avenge for his father’s death. In addition, Kemal too worked in many odd jobs trying to support his mother. He took on jobs as a cotton-picker, farmhand, construction foreman, clerk, cobbler’s helper as well as numerous others. His experiences in these jobs formed his leftist worldview and the duty he felt to help the downtrodden sections of society. His involvement with the Turkish Workers’ Party led him to be branded as a Communist. Throughout his life, Kemal was often in trouble with the police, the Turkish government and the people of his country, ending up in prison briefly and forced to live in France and Sweden before coming back to Turkey for good. It seems that Memed, My Hawk is a semi-autobiographical novel because at times the emotions expressed in the novel seem so real that it’s difficult to tell where Slim Memed begins and Yaşar Kemal ends. This, I suppose, is what makes it such a compelling read.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published in February of 2014. It was updated for relevance on December of 2018.