It’s always a good idea to get out of Istanbul, to escape the traffic, the noise and endless grind of people and machines.

My wife Özge and I usually go to Anamur, a small town on the south coast, sequestered on a windy cape far from the touristy hotspots of Antalya, Marmaris and Bodrum. The flight from Istanbul, goodness knows, was filled with enough of them – mostly European and not a few Russian tourists, giggling and yapping away incessantly, as if they’d never been on holiday before.

We welcomed our arrival in Anamur, with its quiet seclusion, friendly familiarity, not to mention Özge’s mother’s wonderful, home-cooked dishes. With the arrival too of Ramadan, the streets were even more idle and deserted than usual.

The first morning, I got up with my bacanak (brother-in-law) and nephew, and we walked down to the beach for the first swim of the year. The waters of the Med, which are calm in the morning, were chilly when you dove in, but perfect after a minute or so. We had the whole beach to ourselves, and afterward returned to the apartment, where everyone was up and having breakfast on the terrace. (On a side note, Turkey is unique in the Muslim world in that fasting during Ramadan is, for the most part, not strictly enforced – at least not in the west part of the country).

The days we spent idling, letting the quiet of the town drift through the afternoons. My wife and I went to the iskele and sat at a cafe, she with a cup of tea and I with a couple cold bottles of Efes beer (also, no one minds here if you drink alcohol during the holy month).

Anyway, knowing that we would have lots of time on our hands, I brought along my summer reading: Man Ray’s autobiography, Self-Portrait.

****

****

What does Man Ray have to do with Anamur, or with Turkey? Beats the hell out of me, abi. As far as I can tell, he never even set foot here. Little did he know that one day his Self-Portrait would wind up on a shelf of Pandora’s, a small bookshop just off Istiklal Caddesi in Taksim, waiting to be snatched up by the latest passing yabancı.

That’s where I found him – or rather, he found me. I have always somehow overlooked this highly influential 20th Century Dadaist and Surrealist painter-photographer. It was really an unbelievable oversight, considering that I like to see myself as somewhat knowledgeable of modern art. And he’s a fellow countryman on top of that.

Born in Brooklyn as Emmanuel Radnitsky in 1890, Man Ray spent most of his life in France, where he photographed some of the dominant figures of his age – Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Picasso, et al – was great friends and occasional collaborator of Marcel Duchamp. He also dabbled in early Surrealist cinema, alongside pioneers such as Luis Brunel, and even spent some time in Hollywood.

These days, the name Man Ray isn’t mentioned much, but the stamp of his vision, especially his striking and iconic “Ray-ographs,” is felt throughout the visual arts.

What I found interesting was his understanding that photography was an art form at a time when many fellow artists, and the public, strongly felt otherwise. The camera, in effect, had made painting, at least realistic and impressionist forms, somewhat redundant and obsolete – which explains why so many artists turned to Cubism, Abstract Expressionism and other forms.

But Man Ray was ahead of the curve in his understanding that the camera – demonstrated by his famous Rayographs, and his solarized photos – could, in the right hands, be as expressive and versatile as a paintbrush.

“The difference between photography and painting,” he observes in his Self-Portrait, “is that in photography, all corrections are made beforehand, while in painting the process of correction is made during and afterward.”

These observations provided grist for the mill while my wife and I sat on the beach, looking out at the azure Mediterranean, satisfied with the feeling of isolation and refreshing breezes the cape offers. We watched as some local boys plunged bravely into the chilly waters, looking strong, brown and healthy. The horizon was bright, brilliant, lonesome, and you could see the haze of clouds over Cyprus far in the distance. To our backs lay the silent town and the long greenhouses with their bananas that are a staple of the local economy. (I joked to my wife Özge that we could always get work on the banana farms; she replied that these jobs had long since gone to Syrian refugees).

Further down the coast, the mountains stretched their talon-like shapes down towards the sea.

****

I’ve always looked upon my writing as a form of drawing (as a child, my first talent was sketching, long since abandoned; most of us tend to neglect our original talents, for some reason). You could say I identified with Man Ray, in that he also seemed to ultimately see his photography in a similar respect.

I told Özge about some projects I’ve been considering, and how Man Ray’s approach seems to reinforce them. For example, I said it seemed almost pointless, in this day and age, for me to be publishing print books – the cost, the shipping, the tiresome business of hand-delivering the books to local sellers in hopes of selling on consignment – when I could just publish e-books.

“Or make audio recordings,” I added, using programs like Audacity. Except you need a good microphone for that.

“I’m sure we could find one somewhere,” my wife said, showing interest.

Surely, it’s what Man Ray would do, if he were in my position. Embrace the challenges, the advantages, and opportunities presented by the new mediums, rather than cling stubbornly to the old ones, which may no longer be as viable.

I thought of Man Ray telling of Dadaist artist friends who resisted the idea of radio. One such artist, to whom Man Ray had presented a radio as a gift, would secretly listen to it in his studio, but then turn it off when visitors arrived, or else claim he only listened to the news. “Later on when the radio broke,” related Man Ray, “the artist begged me to get him another one.”

In Istanbul, I’d lamented the closing of several good bookstores, and the paucity of titles in many others. And yet, how often, on the metro, the bus, the shuttles, had I seen colleagues, students, and fellow Istanbullus engrossed in an e-book downloaded on their phone or Kindle? Indeed, perusing the Man Ray, I noted that he listened to Joyce and other contemporary authors’ audio recordings, and enjoyed them.

Still, there is something to be said for an old-fashioned book, having it in hand, flipping the pages, inspecting the photographs, especially when dealing with an artist. And yet, the pictures are all black and white. It wasn’t until later, my curiosity aroused, that I had to go online and view the full-color reproductions of such famous Man Ray works as “The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself With Her Shadows (1916),” “Ingre’s Violin (1920),” “Glass Tears (1932)” and “Observatory Time: The Lovers (1936).”

****

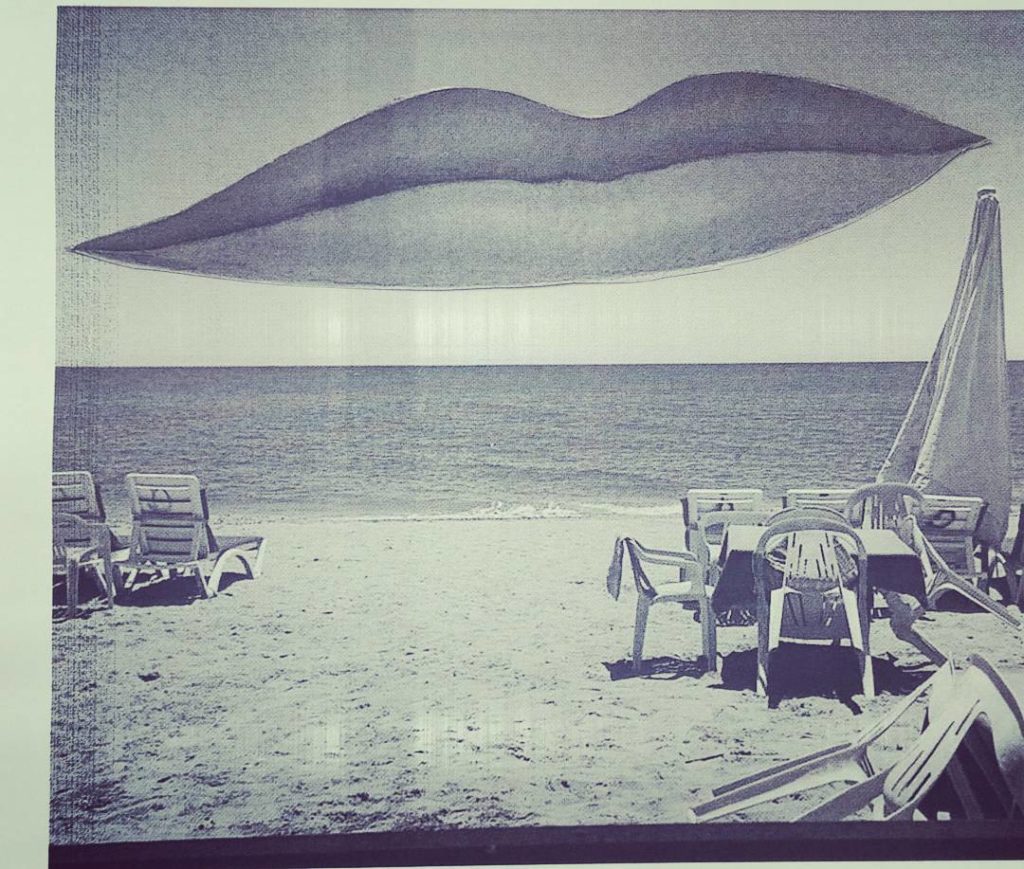

Looking out at the sea from our café, I’d had a vision of those famous, gaudy, sensuous lips from “The Lovers” suddenly appearing overhead, hovering fantastically over our beach in Anamur. I snapped a photo of the beach, cropped and filtered it through Instagram, then went to Google images and found a reproduction of the iconic Man Ray lips.

Alas, I couldn’t manage to download a photo layering app. After we returned to Istanbul, I had an idea. I printed the two photographs, then with a pair of scissors, carefully cut out the lips, and superimposed – positioned – them over the sky in the Anamur picture. With my phone, I took a photo of the completed portrait, adding a bit of color on Instagram.

I liked the result: Photo-layering, done the old-fashioned way by hand, but with a bit of 21st Century help from my smart phone. Also, I was pleased by the synchronicity, or convergence, of my discovery of Man Ray and his work, with our idyllic holiday setting. It seemed as though Anamur and Man Ray, two great sources of inspiration (for me, anyway), were made for each other.

****

The rest of our holiday passed evenly, monotonously, and we had great weather. A friend and fellow Lost Coast refugee, who resides in Ankara, enviously commented on a photo I’d posted from the beach: “Grey, rainy, Humboldt-kinda day here in Ankara,” he lamented.

In the evenings, while Özge’s mother prepared dinner, and my wife chatting with her sister on the sofa, I’d sit out on the terrace, reading the Man Ray and enjoying occasionally looking out at the mountains, the mostly deserted-looking houses, the banana greenhouses.

By the end of the weekend, we were ready to get back to the city. We always are. We missed our cat, our comfortable little flat, and the irresistible allure of Istanbul, its twists and tumult.

“It is Brancusi who said the artist must have some kind of upheaval every few years,” Man Ray writes.

Maybe so, but for many of us here in this part of the world, especially in recent years, upheaval has been the norm. It is the quiet, the seclusion and solitude – a sense of the timeless, eternal world – that Anamur, our tiny corner of the Med, so generously gives year after year, that keeps us coming back, and continues to inspire.

****

James Tressler, a former Lost Coast resident, is a writer and teacher living in Istanbul.