The word “devrim” means revolution.

Does Devrim Erbil consider himself a revolutionary?

“Of course,” he says, without hesitation. “Every day. Every night. I work constantly.”

Indeed, at 80, the permanent revolution of Master Erbil, Turkey’s most famous living artist, carries on at a dizzying pace.

His home/studio, which occupies five floors of a modest apartment building in Suadiye, offers plenty of productive evidence. From top to bottom, the world – the grand, miniaturized world – of Devrim Erbil is everywhere. There are his paintings of course, but also stain-glass windows, rugs, and tapestries and even coffee cups that bear the stamp of his vision.

“I try to use all materials, all techniques,” he added. “I can say I am the most well-known artist in Turkey, but I am also the most productive.”

Looking at the daily results pouring from his revolution factory, it’s hard to argue.

Erbil’s journey as an artist began in the town of Uşak, where he was born in 1937, and in Balikesir, where he grew up. There were no museums or galleries, he recalled, at least not in those cities. His initial interest in art stemmed from literature – stories and poems. It was only later, in high school, that teachers spotted his artistic temperament and abilities, and encouraged him to study art.

“I think it was better for me in the long run,” he said. “Because growing up I wasn’t influenced by any particular artist. I was able to develop my own style.”

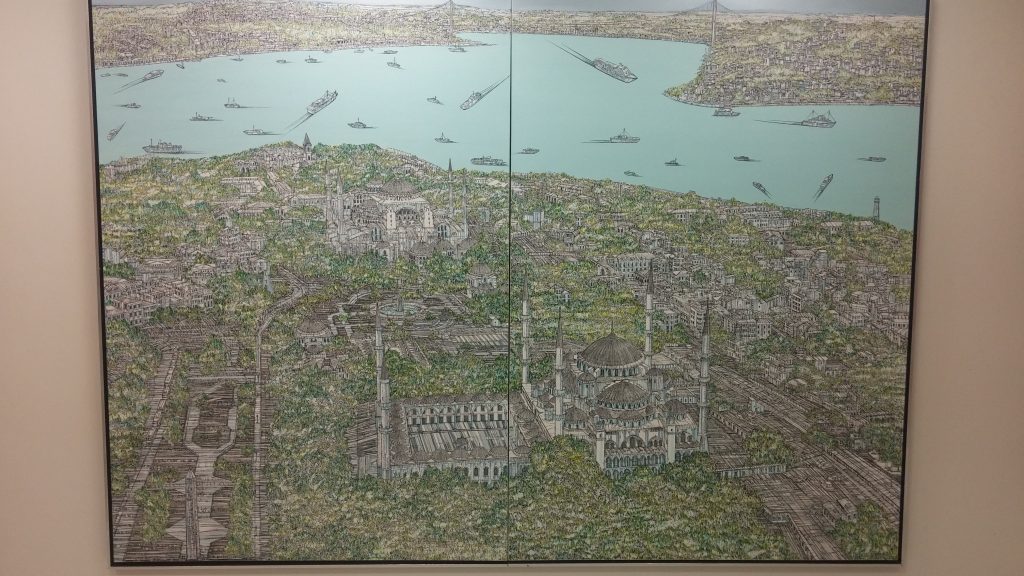

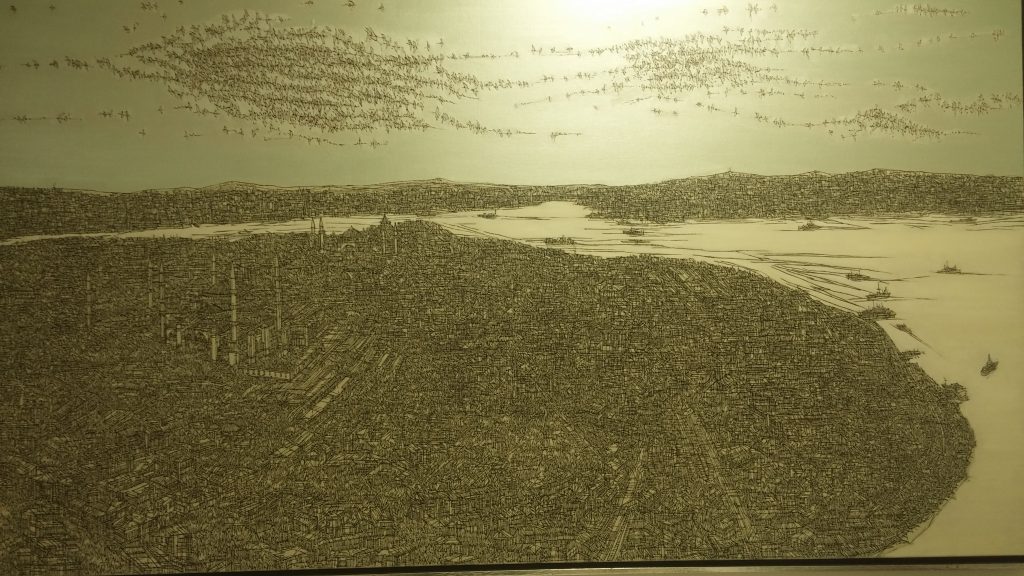

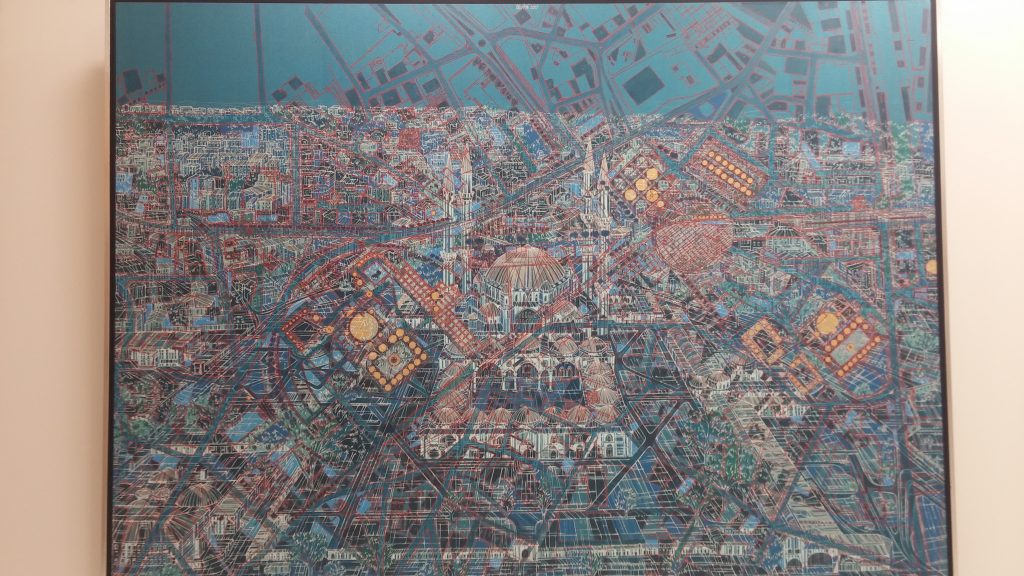

He enrolled at Mimar Sinan University in 1955. It was there that he fell under the sway of Ottoman and Far Eastern art, chiefly 16th Century Artist-Mathematician Nasuh Al-Matraki, and Nakkaş Osman, miniaturist for the Ottoman Empire during the same time period. In these men, Erbil found the flat, non-linear perspective that would later characterize many of his works. Erbil was also influenced by hat, Ottoman calligraphy – “the simplicity and perfection of line.” One can see this in his intricate, precise, but nevertheless graceful, underscoring of figures and cityscapes.

“In Ottoman art, we can see how they engage with the city as a whole, like cartography,” Erbil observed. “They have a different perspective than the linear or atmospheric approach of Western art. In Western art, there are three dimensions, whereas in Ottoman art, there is only two dimensions. Also, in Ottoman art there is a hierarchy in the portrayal of objects (and people). If an object is portrayed as big, it means that it is more important than the smaller objects.”

It comes perhaps as little surprise that the Ottomans – and revolutions – figure so strongly in Erbil’s relationship to art. His grandfather, for example, grew up during the Ottoman Empire and later during the Gallipoli campaign in the First World War, was a police constable and friend of Ataturk.

“I think that’s why I was given the name ‘Devrim,’” he reflected. “Because my grandfather understood the dynamism of that time, the new Republic.”

Istanbul is, of course, a vast intersection of culture, history, people, commerce as well as art. It is a city that often defies categorization, or perspective.

One of the things I find striking in Erbil’s paintings is his seemingly effortless command of the city’s horizons. His pictures gaze and breathe. God knows, those of us who live in Istanbul long enough get into lock step, forced inward by the traffic, the noise, the long working hours, the constant demands. Equally, we get inundated by our friends’ Instagram photos on a daily basis – clichéd tinted photos of the Bosphorus, the mosques, the ferry boats and sea birds. At times, you feel trapped.

With Devrim Erbil, one admires his ability to transmute, or transcend, the obvious picturesqueness of the city, as well as its mistress-like moods and demands, to produce what he calls, “poetic abstractions.” A distinct, cat-like vision: once you’ve seen one Devrim Erbil painting, you will recognize his signature style anywhere. You even find yourself seeing the city in his way. And that’s just his Istanbul pictures. His Anatolian countryside pictures could merit a study all by themselves.

I asked his thoughts on the city, and its influence on his work.

“It was Picasso who said, ‘In darkness, all women are beautiful,’” Erbil replied, then laughed. “By that I mean, when I see Istanbul, I see a panoramic view, but inside it is like a chaos. In my painting, I try to get rid of the chaos … How can one not be in love with this city? It has 10,000 years of history, three empires … It has the Bosphorus. There is no city like it in the world.”

On the outside, Erbil projects the image typical to people of the West Aegean. Even in his eighties, he is fit, his face unlined, dark eyes keen and flashing. He offers the same warm, robust hospitality to visitors (he gets a dozen or more a day, from potential buyers to gallery owners to reporters) that you will find in any Turkish home.

You might ask, when does he find time to actually work?

The answer? He never stops.

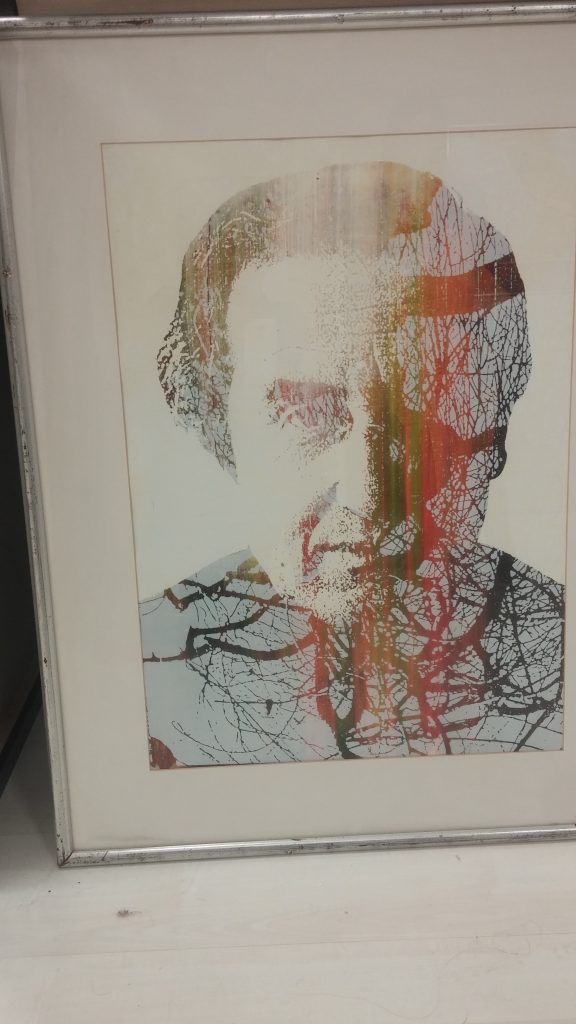

In fact, the Erbil studio-residence (the sitting area feels a bit like a salon) is very much a working studio – a factory, in the same tradition of a Rembrandt school or Warhol’s Factory. You find everything from the current stone mosaic he is working on with fellow artist Suha Semerci, to canvases being produced in his style by a stable of skilled apprentices, to stain-glass windows, to silk screen posters, to a recently completed cityscape that was done in aluminium. In the commercial art sense, Erbil is Devrim International, the artist-as-businessman. But his animus and anima are firmly rooted in his Anatolian and Aegean roots. As Cem Yilmaz would say, “Little, little – to the middle.” He seems to draw upon whatever resources are at hand.

In addition to his Suadiye headquarters, Erbil also has a silk-screen and engraving studio in nearby Maltepe, a carpet-producing studio in Balikesir (and in his native Uşak), not to mention the museum which bears his name in Balikesir. Then of course, there are his ongoing and upcoming exhibitions, not just in Turkey, but also in Poland, Israel and Beijing later this year.

“Right now, as we speak,” Erbil said. “My work is going on. It never stops.”

He is indeed productive. Three marriages produced four children, all of whom are involved in the arts in one way or another. His youngest son Barış, 28, is his business manager, and occasional interpreter (Barış did the bulk of translating for this profile, much to my thanks).

Inasmuch as he is versed in the Ottomans, Erbil seems to be equally conversant in today’s social media. His Instagram page boasts thousands of followers, and he is also moving toward virtual reality.

“Virtual Devrim,” a virtual reality exhibition, is set to open at the Gama Gallery in Maslak in early February.

And yet, the more I thought about our conversation, especially that evening, when I came home and talked with my wife Özge, the more I became convinced that Erbil’s work, as he said, stands delicately astride the Ottoman and contemporary traditions. If his work is revolutionary, then it is not in the sense of Western art. It is not a case of the Abstract Expressionists handing the baton over to the Pop Artists. Rather, it is a returning to more traditional forms of the Ottoman Empire, and to Anatolia. Such an admittedly subjective assessment may indicate, or reflect, nostalgia, a desire to return to the past, but I don’t think so. Instead, the longing (if that is the word) may be more aesthetic, as often happens in art, an instinctive desire to move back, before moving forward (not unlike the Dadaists, for example, who famously yearned for the rocking horse of childhood). To return to basics, to forgotten or abandoned techniques, to reinforce or underscore certain local themes or perspectives, rather than pander or cater to the latest passing trend from Paris or NYC.

“Do some research into Nasuh Al-Matraki and Nakkaş Osman,” my wife urged. “Don’t just pass their names off. It’s important to understand Devrim Erbil’s work.”

As always, Özge is right. Together, we Googled these past masters. Especially the former, with whom we found the flat, cartography style that immediately recalls the style of Erbil. And in the latter, there is the unmistakable sense of visual hierarchy. (Although with Nakkaş Osman, it appears that much of his work that can be found online was in fact later reproduced in the 19th Century, note).

Anyway, with a bit of hat sprinkled in, one begins to at least get a sense of what the artist Devrim Erbil is aiming at: simplicity, combined with a visual hierarchy (a mature artist knows how to assign the importance of the objects in his/her paintings), and an overall perfection of line.

We arrive at the resume. Going into this story, I perused several books written about Devrim Erbil and his remarkable career. It is tempting to go into all his achievements, titles and accomplishments. I could literally devote pages to the galleries, in Turkey and around the world, where his work is displayed. I have said nothing of his three past exhibitions in New York, for example, nor of his current exhibition in Madrid. His academic career at Mimar Sinan University, where he worked as a professor for more than twenty years. The international awards he has won, in Tehran, Alexandria and Kirghizstan.

But these things, I felt, were facts, things that can be looked up. I wanted to convey a sense of the man, the artist, behind the work.

What was the overall impression?

A warm, approachable man who just happens to be a vital, hard-working force well into his eighties. And as I said earlier, an artist with a distinct vision, rooted in the Ottomans as well as in the business of producing and selling art.

Today the revolution factory connects not only the art world, but also business, academia, media, even charity. For instance, he showed me a porcelain coffee cup set, co-produced with the Karaca firm, the proceeds of which go to UNESCO.

“One of my main goals is to interact my art with life,” Erbil said. As I was leaving that morning, thanking Barış and my friend Fatma for setting up the meeting, Erbil was already back to work on his latest painting. He stopped for a moment, wiping paint from his fingers to shake hands in farewell.

Thus, the work of Devrim Erbil, artist, academic, businessman, revolutionary, goes on.

Ed’s Note: Devrim Erbil’s studio in Suadiye is open weekly for visitors. For more information, contact erbilbaris@gmail.com.

Images courtesy of the author.

James Tressler is the author of several books, including the recently published “Inside Voices: A Collection of New Stories.” He lives with his wife Özge and cat Ginger in Koşuyolu.