While the Elgiz Museum is a bit off the beaten path, it is well worth a visit. Located in Maslak, it showcases the Elgiz family’s private collection of contemporary art. Formerly named Proje4L and located in Levent, the museum opened in 2001 as the first contemporary art museum in Turkey. Recently, I had the pleasure of viewing Dissolution, the current solo exhibition of Azade Köker; Skyline, the group show located on the rooftop sculpture garden; and the portion of the permanent collection which is currently on display. Each exhibition has important contributions. For instance, the permanent collection features many core contemporary artists both from Turkey and abroad, with pieces from artists like Gilbert & George, Cindy Sherman, Abdurrahman Öztoprak, Barbara Kruger, Pınar Yolaçan, Sol LeWitt and many more. Overall, I highly recommend a visit to the museum.

However, I sensed an overarching problem – namely, where does the private collection end and the museum begin? It has come to my attention that many private galleries/museums in Istanbul lack a strong curatorial vision, which can lead to exhibitions without a defined perspective. As a viewer, it can make me feel groundless. The high turnover in the curator position, sponsorships that force incongruent shows into a space (this involves essentially bypassing the curator, something I witnessed in the Magnum exhibition at the Istanbul Modern), and curator positions that sit vacant are some of the common reasons why this occurs. Indeed, the means and/or acumen for buying art within the context of a private collection is not the same as curation for public consumption. Curating for the public, at its best, fosters and extends current dialogues, as well as educates, excites and entertains. Lack of a strong curatorial vision can manifest in many aspects of the viewing experience for a patron, including strange inclusions, odd presentation or an overall uneven program that lacks a clear trajectory. This adds up to a lack of connection with the public.

It’s a difficult task to connect art to the masses in a meaningful way, and institutions need a full-time expert on the task. A curator acts as a translator, helping to make sense of art’s coded language by presenting projects with context and reference points. The task must be undertaken enthusiastically and relentlessly. I sense some disconnect between art and the public at the Elgiz (and at other art spaces in Istanbul). On the other hand, they have done something no other museum in the city has done: made an intellectually valuable collection available to the public free of charge. This is one of the most important steps to starting a dialogue with the public, and we, the public, should take them up on this offer.

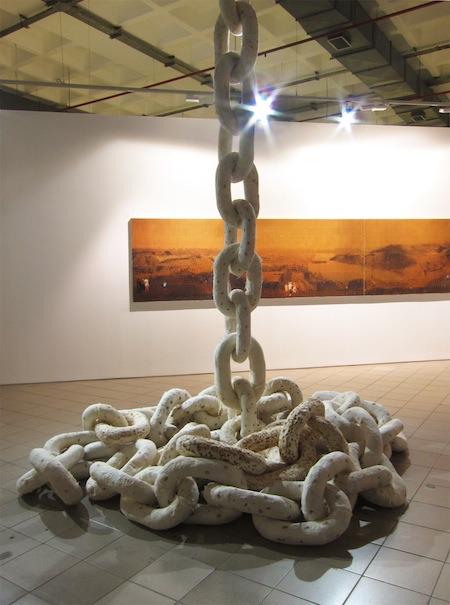

Dissolution, the solo show of Azade Köker, is on display until January and is focused on her recent large sculptural work (2015) and her large-scale, photography-based collages (2011-2014). Köker, who is originally from Turkey but has spent most of her career in Germany, is a contemporary artist and accomplished figure. This show is at its best when the photo-based works act as landscapes for the large sculptures and another parallel reality is evoked, one in which everyday items are blown out of scale and where photographs bend and yet still seem to represent ‘reality’. In these instances, Köker’s intricate world of labor and observation are on display. This ambiance, when taken as a whole is quite engaging.

However, the sculptural pieces on their own do not excite the same fascination. Perhaps I would feel differently if there were more ultra large or very small-scale works, as the mid-sized work is less compelling in the space. While the large chain titled Dissolution (2015) and the delicate tree titled Rhizom (2015) are obvious highlights, the inclusion of Gelinlik (Bridal Dress, 2009) and the video piece Stillness (2013) seemed a bit like an unfinished thought on feminism that I couldn’t directly connect with the photographic work. Likewise, the inclusion of a video with the sculpture Abandoned City (2015) acts to distract from rather than compliment the piece. Köker is quite prolific, so in the future she may make works that can bring some of these elements into closer conversation with one another.

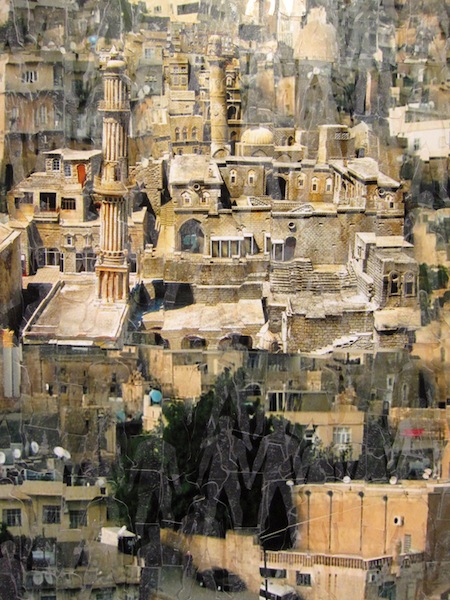

On the other hand, her photographic collages are solid and fully conceptually realized. Köker has perfected the beautiful execution of these collages, which are dense with detail and subtle in their colorscapes, both busy and vast. These layered and spliced-together panoramics are layered again with a transparent medium (tape), which often also takes the form of something – a skull, a person, an abstract shape. This creates an ephemeral layering and adds multiple changing perspectives to the work. The masking encourages exploration and points to obvious manipulation of the image, yet reassures us of her sincerity and seals them off into something indisputable. I found this to be a very contemporary and refreshing way of exploring the (non)representative, nebulous qualities of photography, which take the works far beyond the medium into truly beautiful mixed media creations.

Yet I could not always draw a line from her photographic collages to her newest sculptural works, and I believe this can be chalked up to the lack of a strong curatorial hand. An artist is truly an expert on their own work, but like an editor for a prolific writer, a strong, thoughtful curator elevates the strengths and mitigates or contextualizes the weaknesses. With this show, I feel like I am looking at the edge of her practice. It’s as if the page is folded and the text continues out-of-sight on a perpendicular plane. It remains to be seen if Köker will continue working in sculpture, but I would welcome the opportunity to see more of the large-scale works interacting with one another. We’ll see where the vision of this prolific artist takes her next.

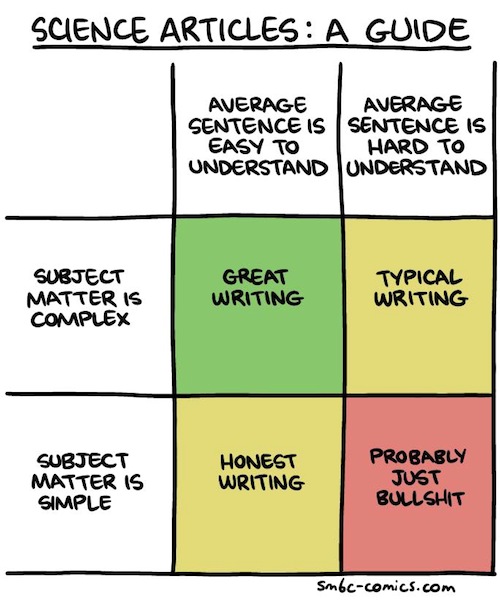

Typical of many exhibitions in Turkey, is it accompanied by a large, beautifully printed catalog. However, the hardcover volume seems more suited in size and expense to a retrospective which, in the introduction, Can Elgiz assures us this exhibition could be… but it’s not. While a number of accomplished critics and writers have been enlisted to contribute to the catalog, it lacks a short, clear and concise description of the work and theoretical underpinning of this show (see the above table). It begins with a quote by the artist, which is followed by a dramatic and somewhat confusing introduction by Mr. Elgiz. Here, he (incorrectly) writes, “Conceptual art is rare in Turkey.” Why would he say this? When Sevda and Can and Elgiz started their collection in the mid 1980s this may have been true, but it is by no means the case today. For people who feel the same way he does, let me recommend exhibist magazine, and in particular this column by accomplished conceptual artist Işıl Eğrikavuk, which makes the only partially tongue-in-cheek argument that Turkish society may be inherently conceptual. Or go visit one of the many hundreds of art happenings posted on Yabangee every year.

Reading further, the catalog includes a number of somewhat surprisingly dated references. First, there is the use of an interview with Paul Virilio from 1999. While the interview has an accompanying essay which I am not privy to, as it is the only thing in the book that is not translated into English, it seems hard to understand how something almost 18 years old could bring us to “avant-garde art before the contemporary”, as was written in the Elgiz introduction. Moreover, the use of the term “Afro-American” in the essay of Ahmet Ergenç is odd. It has long since fallen out of favor and use, and some would consider it offensive. His point could have been made with a more timely example that doesn’t carry so much baggage. And finally, the term “Turkish Art” shows up in much of the printed material for the Elgiz. Recently there has been a shift in language, and it is more common to use the phrase “art from Turkey” as opposed to “Turkish Art”, mainly because the former is more inclusive of those Turks who come from different national backgrounds, including Kurds and Armenians. All together these missteps add up to a dated and somewhat stuffy presentation.

As a counterpoint, the juried sculpture exhibition Skyline, which is presented on the terrace, is the opposite of stuffy and dated. The Elgiz Museum has turned its roof into an art oasis and a form of outreach to sculpture artists from Turkey. With over 30 pieces by artists from all over the country, the view and raw, almost wild exposure to the elements makes for an invigorating art viewing experience. I may have wished for more benches and landscaping, as well as a less crowded presentation, but this unexpected access is literally and figuratively refreshing.

While being the first contemporary art collection in Turkey is an amazing claim to fame, it is not enough to propel the Elgiz Museum in the long run. In my opinion, this institution could benefit from a strong(er) curatorial vision (although the Elgiz Museum is not alone in this regard), for the vision of the collector is cultivated in the hands of a competent curator. More new outreach programs, like Skyline, must be executed and fostered. A contemporary art collection is ideally a destination for the makers, thinkers and collectors of tomorrow. As it exists now, the museum is a sort of glorified living room for the Elgiz family. But let it act as your living room, too. Go and view the work, take pictures and ask questions. For it is only with more engagement that the Elgiz Museum will continue to develop and grow.

Missy Weimer is a contributor to Yabangee.

An erudite analysis