Visiting the Sakıp Sabancı museum has been on my mind since I got to Istanbul, more because of its aesthetics than anything else. The substantial villa with its pleasant ascending garden is located right on the Bosphorus next to one of my favorite breakfast spots in the city, Emirgan Sütiş. This area feels like it lies in one of the special spots in the residential side of European Istanbul. I always get the feeling that Istanbul has many facades and moods and this particular one is quite contemporary and Western with an authentic vibe.

This January day started off cloudless and sunny in a refreshing way, especially after days of continuous gloom and occasional rain. Although the weather wasn’t crazy cold, there was crispiness to it that left me refreshed and excited about visiting the Russian Exhibition.

I got inside the gates of the villa premises and went ahead to buy a ticket and to my delight, that day entrance was free! I just love it when culture-related events or exhibitions like this are offered free of charge, not only because it means more money for me but also because it’s an awesome chance to explore places and things that can otherwise make a dent in your budget.

The actual museum is located on top of a hill inside the grounds of the villa and there’s a small streetway that leads you up to the museum while exhibiting the pretty little gardens and sitting spots scattered along the sides. Suddenly you are no longer in Istanbul at this early quiet hour in the morning. It is like being in a garden in Rome where bits of prettiness surround you and lead you to the grand destination which is the actual villa.

This romantic perspective on things was mostly a result of the combo of greenery, culture, the serene water of the Bosphorus and the calm that engulfed the area that morning.

It was soon to be shaken by the history I encountered inside the exhibition.

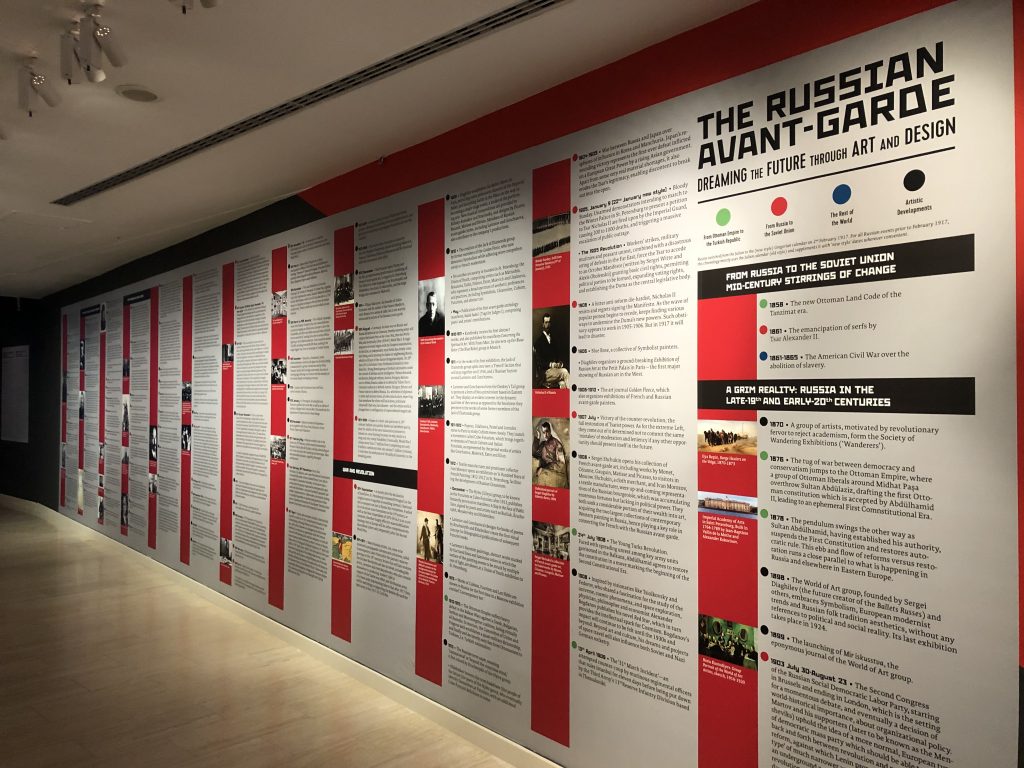

After taking lovely photos in and of this mood, I go in the exhibition to find written on the walls a breakdown of events that unraveled in the world at the turn of the 20th century, and you know what that means; yes, disaster!! The beginning of the 20th century up to its midst, the world witnessed two world wars, many revolutions, and a lot of political struggle. Russia was very involved in all this of course and before World War One, Russia had its first revolution in 1905 and just before the Great War ended, another revolution took place overthrowing the Tsarist government and placing Lenin in power.

This is written in a lot of detail on the walls of the exhibition and it is overwhelming to see all that printed boldly in front of your eyes. The events are broken down into four parts; “From the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic”, “From Russia to the Soviet Union”, “The Rest of the World” and the “Artistic Developments”. This explains chronologically when political events took in Turkey, Russia, and the rest of the world, and where the Artistic Development in Russia was a result of these influences. It’s a very clever and thorough way of giving an overview of the world, and quite diligent.

Following that detailed overview of the world at the turn of the 20th century, you see a small screening of what looks like official videos of some of the activities of the Tsar, which is fascinating to see because this part of history is mostly documented in writing, not seen. I spent a good 15 minutes at the entrance of the exhibition reading about world events intertwined with the artistic evolution that accompanied these life-changing incidents and believe it or not, I didn’t feel the time passing. It was an intriguing snap-shot at a time long forgotten.

The exhibition’s name is “Dreaming the Future. Russian Avant-Garde Art and Design” and the artwork was collected by the famous George Costakis, a Greek art lover and collector who lived in Moscow at a time when the Soviet Union frowned upon ideas like collecting art and doomed it as “hoarding wealth” and “bourgeois throwbacks”. What is apparent throughout the collection is the great passion and dedication with which Costakis acquired and preserved these pieces of art.

While the exhibition comprises mostly of paintings, there’s also some structural art involved as well as videos of documentaries and testimonials about the different pieces or about the art collector himself.

The paintings start off, delicately, with depictions of scenes of nature that are almost romantic in nature. The colors used are mostly calm and intricate reflecting a simple lifestyle and a more meditative mood. One of my favorite in this part of the collection is a painting showing a pond in winter reflecting snow covered trees that resemble Willows. The pastel colors mixed with the white snow emit some beautiful calming vibes. Another painting that caught my attention was almost the opposite of the former painting. A pond and trees in the summertime represented in bold deep colors as if to say “snap out of it, it’s activity time!”. That was a reflection of the current January which was very chilly and the yearning for activity and warmth.

In the same hallway as these romantic paintings, you can also see pencil and charcoal miniature paintings. It’s like the artist was trying his hands at representing individuality, at being unique and staying away from the classic art. And although the hallway is filled with art from different artists, the whole rhythm of the exhibition shows you that it was more of a national direction. You can see this more as well with an artistic focus on people rather than landscapes, and family rather than a group. A bunch of paintings by Ivan Kliun shows images of his wife and family, also reflecting that particular painter’s ideology and interests in the 1910s.

A set of magnificent prints follows you on the journey inside the exhibition and I say magnificent because their colors are extremely striking and attractive that they compel you to stop and see, in delight, what they’re about. These “Lubok Prints” -as indicated by a large plaque on the wall- were an inspiration to Neo-primitive artists and later a base to build on some patriotic pieces of art. The prints depict characters and anecdotes from historical, religious and cultural backgrounds in a primitive way aiming mainly to reach the illiterate. They look like wacky comedy cartoons and their “cuteness” is basically intentional and attractive, so much so that modern artists decided to use the same method of printing for political reasons, to reach the masses who were to become vital in the conflicts that were to come.

The next striking presentation is titled “Myth-Making” and you see a very rough documentary/footage that is a staged re-enactment of the “Storming of the Winter Palace” which was used later in a film about the October Revolution, basically creating a surrogate reality about events that led to the deposition of the provisional government. In reality, there was no storming of the palace and no masses to do the storming. Members of the Red Guard units were sent to seize all the key points in Moscow and St. Petersburg. This is a plain example of how media, especially the very young filming techniques were used by the Russians and almost all political forces -up to this very moment- alter reality and create emotions and ideas that are less than true.

From this point on in the exhibition, I began to feel a sense of struggle in the art depicted. The different pieces started to get more complex; the structure was not flowing, a lot of patterns were intertwined now with darker than usual colors and the lines were not smooth. Geometrical shapes were very prevalent at this point and a structure looked like it needed to be present.

And indeed, I move along the floors of the exhibition and the ground floor shocks me with a huge wooden structure of something called “The Magnificent Cuckold”. It’s a mix of patterns, wheels, and cogs that move in relation to each other. The natural color of wood along with the bold red and black are the only colors making this structure. This piece of construction was part of a stage production in 1922 and it is the perfect example of how art was trying to move into life to reach the masses. This big in your face structure is the artist’s way of not deceiving his audience. He wanted to say that “this is the way things are, this is how big and complex life is and it’s up to you to deal with it however you like but you definitely cannot ignore it”, another plaque on the wall so indicated. This structure stands at the entrance to the ground floor which also signifies a transition in the Russian art scene, for now, you can see how the revolution and struggle were things of the past and you detect from the different structures the artists’ need to rebel and break free. The colors are back, with a vengeance, to the different pieces. The complex patterns are still there but seem more inviting, like they want the audience to be compelled to ask and be curious about the meaning behind it all. And it is no wonder as well that after this time of struggle, the Russian artist has started to be interested in the outside world, the world outside himself and his country.

You start to see that there’s an emerging interest in space and the cosmos based on -surprisingly- works of art from the early 20th century artists. The need to “break free” and to break the constraints of humanity and “the physical” seemed very attractive and was, in fact, the inspiration behind the Russian Space Program that launched the first human into space, into the unknown. The images I encountered at this point of the museum were almost surreal and fantastically colorful. It’s as if they were extracted from the mind of a hopeful, dreamy person who wanted to share his futurist fantasies and eventually make them come true.

I went into an adjacent room and right there suspended against the black colors of its walls were magnificent delicate wooden structures of wings, airplane skeletons, and different geometrical shapes. This is the beginning of the era of Cosmism, an expression I first read about in this exhibition and its a continuation of the Russian artist’s fascination with the outside world, the universe and the journey of the human being in search for himself. This continues on in an artistic movement, also amazingly starting very early in the 20th century, called the “Electro-Organism”. It was concerned as well with the origin of man, how he came to being and where he’s going. I think that the turmoil and struggle Russia went through at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, totally affected its sensitive population, the artists. It was time for them to analyze the reasons for their existence in the middle of that change and to go back to their internal selves to see how they’ve grown as human beings in the process. My work as an Energy-healer has me philosophize what I see in some depth and I think that when a change occurs, a lot of ideas move, shifts happen in the consciousness of the people involved in the change and that’s how they grow and move from one phase of their lives to the next. I could see this clearly in this museum.

The transitions in art presentation are very well organized by the curators in the Sabancı museum and they help you see the stories of change and conflict quite clearly, from their perspective at least.

One last part of the exhibition worth mentioning is the area dedicated to the original collector, Mr. Costakis. He truly did seem like a genuine lover of this kind of art. It shows in his home -whose pictures are displayed in his dedicated corner- along with images of himself and a documentary with footage of himself and the people who knew him. Lots of love from Istanbul, many years later, to his lovely soul.

The exhibition continues until April 2019.

All photos courtesy of the author and Sabancı Museum.