Dayla Rogers continues her conversation with artist and researcher C.M. Kösemen about the Dönme and their history.

You are a person of Dönme background. A lot of people with a Dönme background don’t know it. How did you come to understand that?

Whenever I bring this up at the family table, they still laugh at me. Only in the last couple of years have they been giving it some amount of credit. Let me begin by stating that I am not from a distinctly Dönme family. That is to say, there are some families whose both maternal and paternal sides were Dönme and have been brought up with their traditions for two or three generations. I am not like that. Our family is more mixed, including Bektashi Turks from Crete and Balkan Muslims. We have some Dönme members, however, on both my mother and father’s maternal sides. I know this from the certain family anecdotes, where they are from, and the trades they were involved in. Also, I have certain members of the family who lay interned in a cemetery in Izmir that is more or less known as the burial place for the Dönme.

In fact, my brother was dating a Jewish girl and when she said she had a boyfriend whose surname was Kösemen, her grandmother immediately said “Ah–so they are Dönme!”

Were there any traditions in your family that made you curious when you were growing up?

Yes, my father always lights a candle at the doorstep. Also, when he was a kid, his aunt in Izmir would leave out milk and cookies for a certain “Taktakçı Baba”, who would come knocking at night. He told me that he was really scared of this Taktakçı Baba character. His aunt’s house was a really beautiful Greek mansion in Izmir in the 1950s, which had been given to them after they came to Turkey with the population exchange. So, he would be trying to sleep there and this sound [knocking slowly on the table] would come from the attic. And he would be really scared. In the morning, he would go to the attic door to find the glass empty. And he would be freaking scared.

I later learned that this is actually a Dönme tradition. Taktakçı Baba was apparently a name for the messiah, Sabbatai Sevi, whose name they could not utter openly. They had lots of traditions like this. Even if their homes was very small, they would keep an empty guest room as emergency accommodation for the messiah. They would have candle vigils with people watching over the sea in case the messiah returned. Waiting for the return of the messiah was a big part of Dönme family traditions, and my father knowingly or unknowingly transferred two of these: the story of Taktakçı Baba and lighting a candle.

He still lights that candle every night but he just does this because his parents and grandparents did it. To him, it’s a nice family thing that he wants to do. If you ask him, he doesn’t care much about the Dönme thing or whatever. But when I told Osman Hasan’s nephew about this candle tradition and this Taktakçı Baba story, he told me that he had very similar stories in his family. Only it’s “Sütçü Baba” not “Taktakçı Baba” in his family.

Turning to the study of the Dönme, they are often referred to as “crypto-Jews.” Can we really refer to them that way?

There are different schools of thought on this matter. Some scholars say these people, the Dönme, identified as Muslim for centuries, prayed in mosques, and practiced Muslim holidays. Some of them were actually quite conservative Muslims, so you cannot really say they are Jewish. This is one school of thought. My opinion is different. I say this is a community that until recent times managed their ethnic cohesion. Judaism is not just about ritual, but has an ethnic component as well. Today, scholars still talk about Maranos, Jewish converts to Christianity in Spain, in a Jewish context. So, I don’t understand why you cannot consider the Dönme to be at the very least ethnic Jews who practiced a strange form of Islam.

Were they hiding their Jewish identity in order to save their lives or in order to gain certain privileges within the Ottoman Empire?

The Dönme never hid their Jewishness to save their lives. This was not like Christian Europe. They actually broke away from Judaism. This is why I think most Jewish scholars refuse to accept them as Jews.

In the long run, I think having the public appearance of Muslims did the Dönme some good because they found it easier to get into the hierarchies of Ottoman bureaucracy. However, this was not the intended effect. They just broke away from mainstream Judaism because of their belief in this strange Messiah figure Sabbatai Sevi.

My understanding is that for a few decadeds the Dönme lived as crypto Jews, but then they took it to another level and they became not crypto-Jews but crypto-Dönmes. They invented a religion of their own complete with belief in reincarnation and liberal borrowings from Sufi folklore. It was this unique faith that they were hiding behind a Muslim identity.

You mentioned in your book that the Dönme often had distinct clothing and hairstyles but were hidden at the same time. How recognizable were the Dönme during Ottoman times?

This is the methodology of an open secret. Like with the cemeteries, if you are a member of this community, you can easily recognize your fellow members. But if you’re a member of the general Muslim community, they would just seem like some people who have strange clothing or tombstones.

We know that in previous centuries, the deeply religious members of certain Dönme groups wore certain clothes and cut their beard in a certain way. They could tell each other apart and even the local Turks and Muslims would recognize them as a unique type of Muslim.

Do you think that the lack of mass media at that time might have had something to do with the success of that kind of open secret? It seems like it would be hard for that kind of thing to perpetuate in this day and age.

No, it couldn’t remain a secret today. Mass media divulges secrets. At the same time, there also wasn’t the same kind of hype machine or the same kind of hatred and antagonism before the mass media. The Dönme were only seen as evil after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of nationalism in Turkey. Before, the the general term “dönme” (meaning someone who converted to Islam) was an honorific term. In Ottoman times, members of the palace staff were almost overwhelmingly Greeks, Armenians and Jews who had converted to Islam. In fact, because the conversion was a conscious choice, that kind of Muslim was preferable to someone who had been Muslim for ten generations. These converts usually brought different modes of thinking into an Islamic context and enriched the religion and government. Only after the age of nationalism did the main body of Turkish population begin to regard non-Muslims and exotic Muslims as undesirable outsiders.

It sounds like it wasn’t just about allowing one group to dominate but also making people choose sides in their identity and not allowing people to exist in between.

There were many other syncretic minorities in Ottoman times. For example, we know that in the Black Sea region there were a lot of people who practiced Islam and a cryptic version of Greek Orthodox Christianity together. They were descendants of Greeks who had converted to Islam. They still went to church secretly and the imams doubled as priests. So, there were a lot of these identities. But the rise of mass media and the nation-state—not to mention the ethnic conflict during the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire—caused feelings of insecurity to metastasize into oppression and nationalism that said, “You have to be this kind of Muslim, this kind of Turk.”

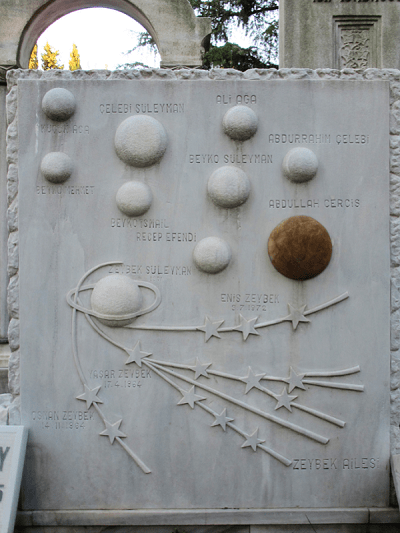

In a way, the tombstone portraits in my book are a nice visual survey of one of these various peoples in Turkey just one generation away from this forced assimilation into a generic identity.

Marc David Baer said it’s really difficult to crack through the culture of secrecy when studying the Dönme.

This veil of secrecy exists because of two reasons: First of all, people could still be scared of an attack on their person or family name. They are afraid of beıng labeled as hidden Jews. If they are doing business with the government or something, you can see how the secrecy must be maintained even further. Secondly there is still a present-day branch of the Dönme, the Karakaş, who still keep to themselves and who have a body of hidden folklore for family members only.

So, because of fear and the last slivers of self-awareness, the Dönme identity is hard to crack into. Even if you broke into it, it would be like entering a giant crypt and finding only dust and a couple of bones inside. For most families, like mine, what you are left with is not like “You are actually a Jew, my son,” or some hidden purpose or something. No. It’s just some barely-remembered anecdotal folktales or maybe some Spanish language songs. But if you spoke to the right people in the right way, I’m certain that you would uncover a lot of things.

What kinds of topics are waiting to be researched?

If I had the time, I would do two Ph.D. theses: Firstly, I would transcribe and translate the epitaphs in Bülbülderesi Cemetery. The tombstones are actually weathering away, so there’s much preservation work to be done. Secondly, I would try to collect miraculous anecdotes about Sabbatai Sevi and the Dönmes from the vast lore of Mediterranean Judaica. There are some very interesting fragments. For example, I bought a book from a local synagogue while on vacation in Rhodes last summer. There it said that Sabbatai Sevi, the Dönme messiah, was in Rhodes for a couple of days and that he had performed a miracle there. There were 12 people sitting in a circle. He took a bundle of 12 sticks and through telekinesis or something made them suddenly stand up like a platoon of soldiers coming to attention. He then made them fly to each member of the community around him to denote their importance.

Now, this cropped up randomly in a semi-touristic book from Rhodes. Who knows what else is waiting out there? If you sifted through the literature, who knows how many miraculous anecdotes you would find about Sabbatai Sevi? One could use these to reconstruct the details of the Dönme religion.

Epilogue: C.M. Kösemen found the shards of Murtaza Bey’s porcelain photograph in the dirt next to the tomb (see Part 1). He has had it reconstructed.

Mr. Kösemen has also been invited to speak on his book “Osman Hasan and the Tombstone Photographs of the Dönmes” at the Australian Association for Jewish Studies 2015 Conference in Sydney, Australia this February.

Great read!!

There are endless avenues to be explored – and each one so fascinating. Thanks so much for this interview, Dayla!