Gökhan Yücel is the founder and curator of the “Anatolian Rock Revival Project”, an initiative which understands itself as a cultural heritage platform, bringing back to life many of the forgotten gems of Turkey’s “Anadolu Rock” music from the 1960s/ 1970s. Apart from retrieving incredible music works from that time and being invested in sharing them with as many people as possible, the project also works with illustrators, who create stunning artworks for each of the songs. What drives this initiative? I spoke to Gökhan to find out more about the project’s roots, ideas and aspirations.

Why did you start the Anatolian Rock Revival Project?

I was born in August 1980. Growing up, I never had the chance to listen to these songs, so the project is kind of personal for me – and I am not the only one. There are millions like me, who never had the opportunity to connect with their history. For someone from outside Turkey, it may be a really good dramatic plot but for me, it’s a personal tragedy. Our project uses songs to talk about a certain historical and political period. What’s more, there’s a specific reason why we stop sharing songs that were created later than 1980. Listeners might start asking questions and our project slowly fills the gaps.

By finding out about more, they can also understand how we became like this. But even more, they can start to imagine what we could be. Turkey could have been a lot better. We have great people here – creative, full of life. However, many cannot believe that anything good can come out of these lands. It is because they are not aware that these things happened. If we don’t know this, then we are also unable to stand on the shoulders of our giants. With the project, we want people to learn about their past, connect with it and start to believe that they themselves can do do something beautiful again.

The music you are sharing has first been published before you were born. How did you come across Anadolu Rock, then?

Days after the Gezi Resistance in 2013, we were watching the footage from the park. Boğaziçi Choir’s music was playing that night. While the videos were streaming in auto-play, an interesting song popped up. I’d never heard of it before. It was a track from 1968, Batman Orchestra’s “Şeker Alalım”. It sounded great. It was immediately followed by another piece, this time “Çayır Çimen Geze Geze” from Mavi Işıklar, released in 1966. It was also beautiful. I kept on listening, and every time I heard another good song I was asking myself: “How could it be, where did these pieces come from?” I kept listening and listening, making lists, learning not only about the bands, but on top of that, also finding out about the reasons as to why we never heard those songs before. In the end, I told my friends about this. Could we make a project to revive these songs? We could come up with beautiful illustrations for songs from that era, and use those to teach people about the songs and make them listen to these tunes.

Could you talk a little more about the reasons those songs have remained mostly unknown throughout these last couple of decades?

There are different opinions on this topic; this is my take: The main reason we don’t know about these songs is the 1980 coup, of course. As a result of it, they banned albums, bands and singers. Selda Bağcan got arrested. Cem Karaca had to live in exile in Germany. Edip Akbayram couldn’t make an album for years. Lots of names couldn’t find any screen time on TRT (which was the only channel on TV at the time). What’s more, this coup also led to another outcome: the auto-censorship. People were afraid to listen to or share these songs, teach them to their children, or talk about what happened. This is also the reason for the apolitical generations that grew after the coup. Now, we can clearly see what the coup caused, but at the time, people just wanted to protect their families by not talking about these topics. Lastly, there is a technological aspect to it. Cassette tapes became a thing in the second part of the ’70s, but they saw their peak in the ’80s. Therefore, most of these artists were not able to change the medium, in order to reach wider audiences. Their vinyls couldn’t get the right treatment while being adapted to cassette tapes. Over time, CDs became popular instead, and so on. Today, we know about these songs because of the internet. People who held on to their recordings started uploading them again, so they resurfaced via YouTube, Soundcloud etc. If it wasn’t for the uploads, only the collectors would still have the songs.

How do you choose the songs which end up being published?

As a first rule, they have to be produced between 1964 – 1980 (from Burçak Tarlası up to the 1980 coup). We listen to hundreds of songs and try to choose pieces from the rock genre, but Anatolian Rock is an umbrella term for more than one genre from the time, so we can stretch the rules if the song is great. Further, we don’t only want full “türkü” songs; there has to be a mix, a new product and sound. It’s mainly me choosing the songs, but I also ask others, experts, about which songs they think should be included in the project. Those ones go into the pool as well. However, in the end, the illustrators are the ones who give the final verdict on the songs. We never tell them what to draw, so if no one chooses a song that we like, we don’t feature it.

Why did you choose not only to dig up songs and share them, but also to work with illustrators?

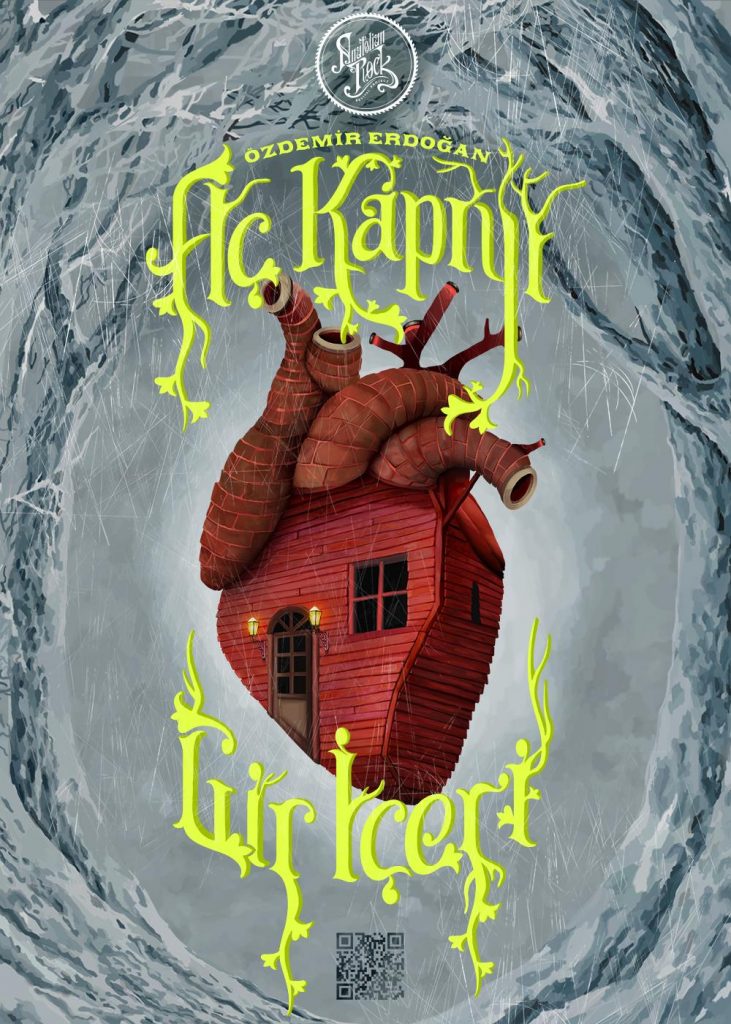

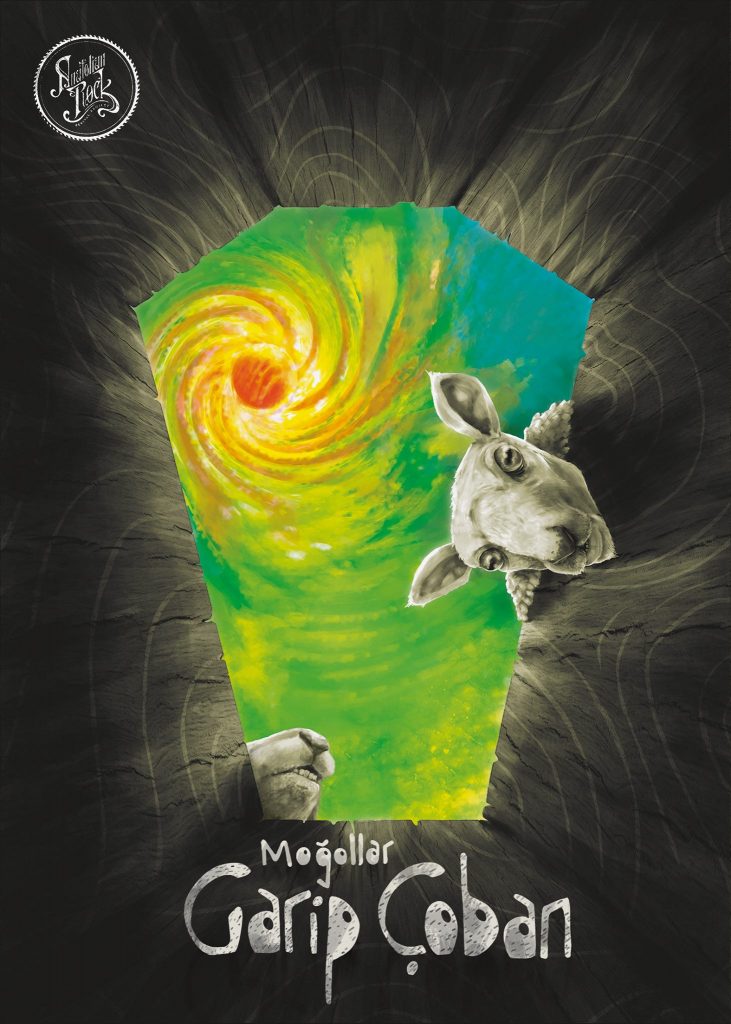

Creating a new language was our goal in terms of content design, which a lot of our time goes into. We ask ourselves how we can make the whole topic more attractive, easier to digest and to raise people’s curiosity to get into the habit of finding out new stuff and research themselves. Because of this, we went with an “easier to understand and colorful to consume”- approach, in which we mixed music and visual arts. This is something that helped us big time. Often, when you search for these songs, you are likely to see a picture of an old recording or photos from that period. In contrast to that, presenting beautiful illustrations and using them as a tool to interpret the songs has made us stand out in the crowd, turning it into an ID by which anyone can instantly recognize us.

What are your dreams and goals for the project in the near and far future? Further, if one is intrigued about the project, how can they support you?

We are very ambitious about the future of the project, because there are lots of things to be done. We feel that it’s time for this project to travel the world and for others to learn about it. We have been preparing all the content for this from the beginning. All our songs have English subtitles and descriptions. We also think that the political and historical story behind this music would be intriguing for anyone. Also, we have wonderful songs and artworks. This is a unique project. So showing it to people outside of Turkey is our number one ambition. In the beginning, we just wanted to create artworks to pay homage to the era but now we want to become a digital music library for the subject. We are working with great people when it comes to analogue mastering and digital remastering processes. So, if we can turn this into a decent music library, it would be a huge win for us. In the near future, we aim to work on a documentary which tells the story of these songs and the Turkish history connected to them. Within this process, we will start by interviewing people from that time: band members, artists and so on and we’ll see where it goes from there.

There are two ways to support us. The first one is through Patreon. We don’t have any sponsors or any help from any official government agencies, so we rely solely on our community’s help. We came up with special presents for our supporters. For example, this is the only way a person gets one of our precious posters. Another way is to share. We’re trying to reach music portals, blogs and newspapers to tell about the project. We need to reach more people, especially outside of Turkey, so sharing the project is a big help.

If you now also got curious about the Anatolian Rock Revival Project, dig in and discover via their official pages on Youtube and Instagram.