“There are just three rules: No Racism, no sexism, and no homophobia.”

Rules? I thought this was an open-mic event. There shouldn’t be any rules.

“You have six minutes on stage because after six minutes, you may lose your connection with the audience.”

A time limit? I brought a chapter of my novel. I’ll never be able to read it in just 6 minutes.

“And next, we’ll have … Erica. Please welcome Erica on stage.”

She called me last — I doubt anyone’s even listening anymore!

Everyone has an opinion at Spoken Word Istanbul, but this doesn’t dissuade Merve from hosting it like clockwork every Tuesday night starting at 20:30 at Arsenlüpen. She’s a petite, stylish writer who resembles Winona Ryder and has remained the dedicated organizer of the event since starting it in 2012 (apart from a one year hiatus in 2014-2015). She transported the idea from Paris, where she used to be actively involved with a similar event. Of course, for an American like myself, the name Spoken Word sounds like an artifact from the 1990s for when rap met poetry and the moniker became widely recognizable. Yet, here in Istanbul, name recognition helps lure interesting transients to the event.

The event is a free, open-mic event for self-appointed performers to read literary works or to perform via any other media on stage. Usually, the performers use English, but all languages are welcomed. Merve speaks humbly about her role. She knows that such an event needs commitment to keep it going. For any new project, “Only you will give it utmost dedication,” she advises.

According to Merve, the founding value of Spoken Word is freedom of expression: “It is a place where you can express yourself without fear, judgment, or [even] persecution.” However, this freedom does not simply produce nice, easily digestible results, either. Merve likes the element of confrontation that arises from Spoken Word. People can safely contradict each other’s ideas, lifestyles, and concerns in a tolerant environment. She believes that the undercurrent of confrontation is the most valuable part of Spoken Word. Diversity, for Merve, is not just a pleasant idea. It means the ability to bear something uncomfortable.

I recently attended Spoken Word Istanbul on Tuesday, February 14th — the day of heartache. It seemed I was an anomaly for having attended with my boyfriend. On the way, we dodged a few restaurant promoters targeting us to sit at their tables. Beyoğlu felt sleepy, especially for a holiday. Upon entering the building, we risked taking the rickety elevator so as not to climb the mountain of stairs to the fifth floor establishment. Pressed up against my boyfriend, I felt more comfortable than I would if I had accompanied a stranger. I can only imagine the awkward exchanges that must take place in that compressed lift. Finally, we arrived into the cavity of the bar where rows of seats were inhabited by talkative clusters of individuals. The crowd seemed arbitrarily gathered together in Istanbul. It might just as well have been Bangkok or San Francisco. My friend waved from a tall table where she had saved us some seats. She was the first reader and she used the stage to reflect on a recent break up via poetry. I indulged in the Spoken Word material as one-by-one the performers poked holes into the artificial construct of Valentine’s Day.

Some people sabotaged the theme of love. Some people praised it. Some people avoided any theme or variation of it. Yet, nowhere have I seen the fourth wall of the stage be so mercilessly broken as I have at this event. In one performance, the audience was repeating after Nio, the Italian rapper on the mic, shouting “F*** Valentine’s Day!” upon his request. The audience was also recorded on video by the performer Abdulrahman, who requested that we all say ‘Happy Valentine’s Day’ to send to Julian, his crush who was spending the holiday alone in another city. A thrilling vocal performance of Nat King Cole’s L.O.V.E. (‘L. is for the way you look at me’) transformed into a personalized second stanza which involved an impromptu lap-dance for a friend in the audience. Spoken Word Istanbul is a hotbed of attempts at creative genius — some of which are successful.

Attending Spoken Word on a holiday proved that people don’t merely attend to socialize. They also go to give and receive timely social commentary. While it may make tastemakers cringe that none of the performances require practice or preparation, this gives a performer an opportunity to deliver commentary that is directly in conversation with our present moment. As Merve puts it: “[Spoken Word] is not immune to what’s happening in the city or the country.” After the Reina attack, she noticed how people’s range of emotions had expanded: “Sometimes people release their anger, resentment, or their helplessness. People express feelings of melancholy in their performances. The tone generally reflects what happens around us. But, no matter what happens, there is still a sense of belonging among the crowd.” This sense of belonging is revered by all of the regulars who find it a “safe space” for expression. According to Paz, a trained theater performer, a regular of Spoken Word, and fellow Yabangee writer, the event has a great “solidarity vibe.”

Merve has felt the need to reassure people that Spoken Word is “here to stay” both at Arsenlüpen and the city itself. She conveys this message on event’s Facebook page, which people usually check to get up-to-date Spoken Word information. As the organizer, Merve feels that it is important to declare commitment to both the community and the area in spite of the many visible traces of abandonment around Istiklal. Contrary to this trend, Spoken Word Istanbul appears to be growing in popularity.

At first, the event was held roughly once a month. After 2015, it was held about twice a week, with breaks in the summer. However, since the end of last March, Merve decided to host it as a weekly event, without a break in the summer. At first, she recounted, the attendance seemed up and down. By now, it sustains a steady audience and set of performers. Why has its popularity grown? For Merve, “Spoken Word Istanbul fulfills a need that remained unexplored [in Istanbul] until it began.”

The tools of the trade needed to create a Spoken Word event are few. First, a pen and paper are enough to create the list of performers. The only curated aspect of the event remains in the hands of the host who determines the order of the performers. Indeed, Merve provides the glue to assemble the collage.

Second, a stage with lights and a microphone helps give each performer a tangible ’platform’ from which to be heard. The seductive allure of these props beckon everyone who has ever daydreamed of becoming famous. For most performers, the stage offers an adrenaline-inducing shift in perspective from passive observer to active provocateur; on stage, anything is possible.

Boo, a tomboyish regular of the event made the following categories to describe the types of performances she has seen: the musicians, the poets, the comedians (“because who doesn’t need a good laugh these days?”), the fabulists (“who celebrate their ability to create fantastic worlds”), and the ones who “just share: their lives, stories, ideas – and it’s amazing how sometimes someone else’s experience can change they way you think.”

Sometimes the stories drawn from life create the most impact. Refugees have explained their encounters with border police on stage. Performers have come out on stage. In fact, Spoken Word Istanbul is at the top of the list for LGBT Friendly Spaces in Istanbul. First-time performers often simply talk about the immense courage it took for them to put their name on the list. Seeing the trembling hands, hearing the wavering voices, noticing the feelings traverse the performers’ faces and hearing them laugh at their own mistakes provides the candid, unplanned honesty of Spoken Word. The individual presence of performers enables them to tell stories that the “distant media” will never reveal. According to Merve: “These stories are resonant and they stay with you.”

Finally, the audience has a certain responsibility to support the performers. The intimacy created by the live self-representation that is unique to the event makes performers especially vulnerable. Boo points out how the performers at Spoken Word are influenced by the audience: “I think listening is as powerful as performing. The people on the stage can sense if the audience is really listening, and that usually makes their performances stronger.” She thinks the most valuable responses stem from gratitude or understanding because this gives the performer a safe space to share. But, if the conversations of the audience gain momentum, enough sound is produced to kill a performance. Merve usually steps in to request silence in such cases. Fortunately, the Spoken Word audience is often comprised of performers with a vested interest in the event than the average bar-goers who just stumbled upon it by chance.

Beyond these nuts and bolts, the organization of the event requires a lot of commitment on the part of Merve and the regulars who have made it their home to truly bring it to life. This is because it is a labor of love as a grassroots, volunteer-based project. Merve claims that she wouldn’t be able to keep this level of commitment if she didn’t believe in the power of the event. This power comes from the constant positive feedback she receives. She explains that it has developed into a community of fun and diverse friends. It offers supportive audiences for new or established creative projects such as the literary journal The Bosphorus Review of Books or the popular stand-up comedian improvisation group, The Clap. The organizers of related performance or literary events can easily promote their own projects on stage at Spoken Word.

By now, I recognize who the regulars are. I’ve personally come to expect Luke, a British man of letters who knows Japanese and who wears well-chosen outfits and reads perplexing selections of literature from his bookshelf. There’s Thomas, a Muslim from Texas who relishes the seeming contradiction of those two labels. He offers multi-lingual readings of poetry (and sometimes prose) in Arabic, English and Turkish. There’s Saina a Persian creative who loves to sing in Persian with her mother and sister on stage — or dance, or just talk. There’s Omar, a Syrian Refugee who offers laugh-out-loud humor via self-deprecating jokes about his love life. There’s Zümrüt, one of my personal favorites, who humorously critiques Turkish people, men, or anyone in a position of authority with such bizarrely incisive metaphors and twists of logic that I keep running her analogies through my head. Once, there was a Skype call with Lisa on stage, after she had left Istanbul. For anyone who doesn’t know Lisa, she‘s an uninhibited Scottish erotic writer whose material ranges from cosmically radiant orgasms to everyday life. The attempt to stay connected with former regulars was endearing.

By giving performers empowerment and courage, Spoken Word Istanbul inspires them to creatively produce work long after the weekly event has ended. For Najat, a Moroccan writer and French teacher: “The spoken word effect goes beyond the stage. As an aspiring writer I was so blocked and worried about my readers that I couldn’t publish anything until I read a poem at Spoken Word… and it made me a better writer. Actually spoken word unleashed the writer in me.” Likewise, Paz depends on the positive environment: “My favorite part of Spoken Word is the freedom and support. I can say what I want and people are supportive of it.” Merve also describes how on a personal level, it has offered her a therapeutic effect. It gave her a platform to channel her pent up emotions, to face fears, and to test out different feelings before an audience. She says it’s important “to know that you’re not alone — you’re in the company of supportive strangers.”

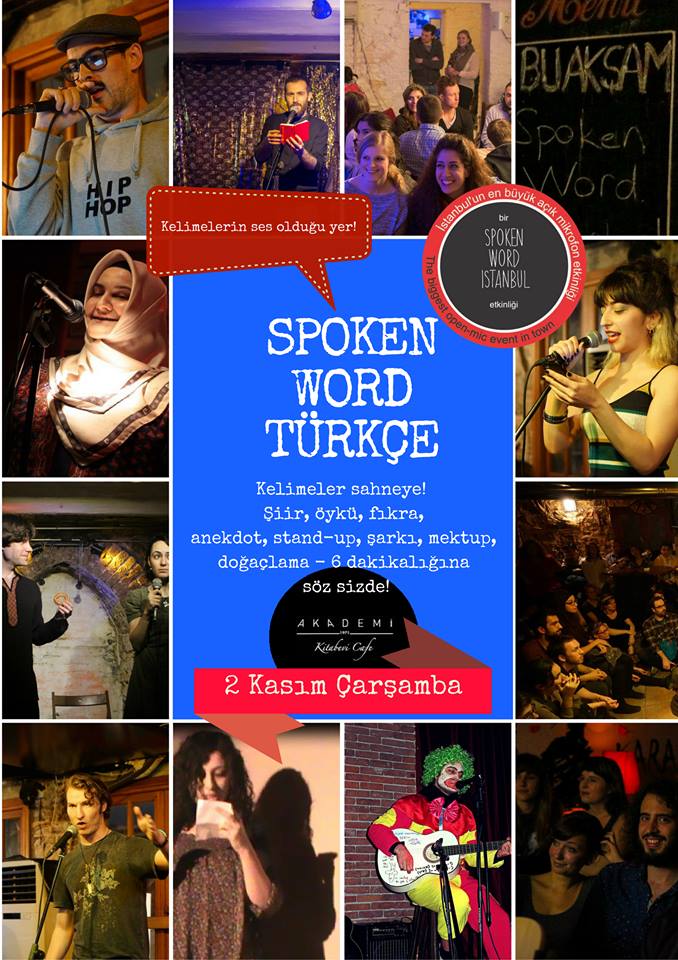

Merve is filled with ideas for expanding the creative momentum of the event. She has recently begun a new iteration in Kadıköy at the Akedemi Kitabevi Cafe: Spoken Word Türkçe. The motivation for Spoken Word Türkçe was motivated by political events. “After the coup attempt, it dawned on me that Turkish people are painfully divided” — not just divisions, but “splinters” separate members of Turkish society, according to Merve. On the other hand, she says, “we grew up together with the same TV programs, the same jokes, the same music from the ‘90s. We forgot that we used to speak to each other.” However, Merve finds herself spending more time contextualizing the event for the Turkish audience, because the notion of an open-mic does not have much precedence in Turkey. Currently, Merve’s priority is to expand Spoken Word Türkçe and to reach out to the Turkish speaking community of Istanbul. She says the project is developing, but it needs to build a community.

She also organized a first-time Writer’s Retreat Datça last June. It was a direct offshoot of the Spoken Word Istanbul event. Merve collaborated with a friend to establish its location at an idyllic space on a seaside hilltop. She says: “It started with an open call for writers and just the right number attended — six people. It was a group of strong writers — all regulars from Spoken Word.” They had talks about each other’s work, gave feed back, and provided lots of interactive support. The second annual Datça Writer’s Retreat will soon be scheduled for this summer. Merve hopes to find the perfect number of attendees again this year.

Finally, the real-estate adage that ‘location is everything’ cannot be dismissed with regards to Spoken Word Istanbul. We share a city where refugees have fled from war zones, expats have fled the high rents of Western cities, transient tourists are passing through, and the mixture of ethnicity that already comprise Turkey adds to the mix. Merve pointed out that the location of Spoken Word Istanbul is not at all arbitrary. In fact, she explained, the Beyoğlu district has a history of ethnic diversity home to Armenians, Greeks, Jews, and Turks while culturally maintaining a strong French influence. The diversity of the area is also reflected on Istiklal by the many different embassies located there. As a result, Spoken Word Istanbul is a place where groups of people who are often considered mutually exclusive nevertheless convene. This includes conservative Muslims and gays, tourists and locals, refugees without passports and Westerners without any restrictions upon their passports.

A communal space of expression, whether it gives a platform to feelings of mourning or relieves tension through laughter, can nonetheless provide a necessary antidote to the weight of events that have impacted Istanbul recently. Spoken Word Istanbul is one of the few events, if not the only event, to grant people a live forum and a safe space for sharing such timely reflections.

All images courtesy of Spoken Word Istanbul.