Some time back, I decided to try a new approach to my Istanbul stories.

Up until that point, the stories, though carefully written, were missing something. They didn’t quite portray the same city I experienced on a day-to-day basis. They were too academic, or too obviously influenced by the work of others. I suppose, like most yabancı, I had more or less docilely accepted the portraits of the city handed down to me in all the tourist guides and history books.

Istanbul is a jumble, a tone poem (I know, the word I’m looking for is ‘mosaic,’ right? No, I’m tired of that word. Just as I’m tired of those endless comparisons of Istanbul to a woman. By now, we’ve all read Pamuk’s Istanbul: Memories of the City, and Şafak’s 40 Rules of Love; nothing against them, but let’s move on a bit, shall we?)

There was an elusive quality about the city that I wanted to capture and have as my own, something you couldn’t find in other Istanbul stories.

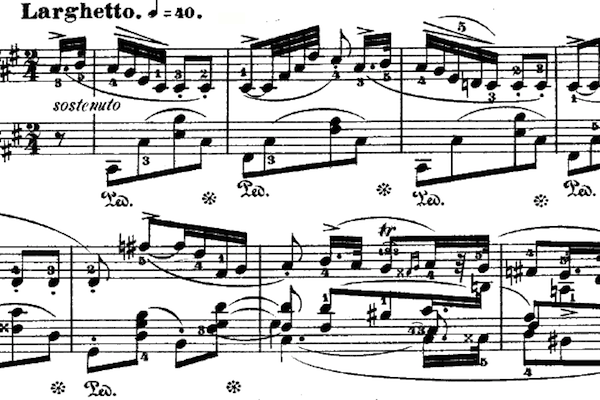

Anyway, one day I struck upon the word “scherzo,” which I vaguely recalled from music studies at university. Just to be sure, I looked up the word in the dictionary. Scherzo (noun): A short, light, humorous piece, usually played very fast. I listened to Chopin’s famous “Scherzo No. 2” … yes! That was the tone I was looking for – nervous, a bit jumpy, sly. Listening to it, you can imagine a cat quietly stalking a group of pigeons pecking at breadcrumbs tossed in front of a fountain. The cat gets close, leaps – the birds scatter, and the sound of their wings beating marks their escape.

Istanbul is like that – a nervous city, full of cats and pigeons (and crows), predator and prey, opportunities and opportunism; in the narrow passages, the sellers, the garsonlar, springing upon the passersby.

With these associations, I set about looking for stories that could be classified as “scherzos.” The first one, “Lahmacuns in the Sky,” was about a Turkish couple’s adventures with a crazy taxi driver while en route to a private clinic for an abortion. The second, “Mother-of-Pearl, was a profile of a spinster-ish Kadıköy landlady who, after years of cheating her tenants, finally gets her comeuppance. Then, there was “Istanbul’s Absurdist Heart,” and “This Matter of Medusa,” both of which were written in a light, ironic tone.

These first “city scherzos” were not wholly successful. They didn’t quite capture what I was aiming at, but at least they were a step beyond the typical, travelogue pieces (“Oh, beauteous Bosporous sunset! Hallowed be thy cliché!”) I had written before. The question, though, was — how to make them better, more scherzo-like?

Well, I could try listening to some scherzos. But, of course! Sitting one evening on the balcony of our flat in Koşuyolu, I put on the famous Chopin “Scherzo, No. 2” again, while my wife Özge was making dinner in the kitchen. The nervous, creeping introductory notes filled the flat, blending with the smell of the köfte. We’d opened a bottle of merlot, so I filled my glass and drank. I closed my eyes, waiting for a sea of city images to arise from the music – not just images, stories, lyrical and terrible, comic, insightful, the kind of stories that are dark but with a clever wink at the end of each scene.

My wife brought in the köfte, set it on the table, along with some bulgar, salad and yogurt. “Do you want ayran?” she asked. “Or are you sticking with the wine?”

“I’ll stick with the wine,” I said.

We sat down and started eating. The köfte was hot, so I dipped it in the yogurt to cool it off. Özge was tired from working all day at her job at the museum. As usual, I’d had a somewhat light teaching schedule (which gave me the luxury of pondering such things as scherzos perching like cats on the park benches of my absurdist city).

“What are we listening to?” Özge asked, pouring some wine for herself. She likes classical music, but generally prefers a more sturdy, amber-lit Bach concerto.

“Do you want me to change it, my love?” I asked.

She shrugged. “No, it’s alright.”

Generally, we don’t talk much when we have meals at home. We ate, while our cat lay sprawled on the rug, eyeing us languidly in the humid air. The sun began to go down, and in the dusk we could hear the cars outside, the horns honking, as tired Istanbullus fought the traffic to get home. A few days before, two taxi drivers had nearly come to blows at the intersection, and had backed up traffic while they stood there, thumping their chests and challenging each other. I’d written a scherzo about it, imagining the two men suddenly breaking into a waltz, dancing hand in hand around the intersection.

But tonight, there was to be no such help from the taxi drivers. An overly vigilant dog, tied to a leash, barked incessantly, challenging every car that passed. Perhaps the dog was trying to help; he was singing a barking scherzo in the key of F major … nah, too forced. I was really reaching.

The Chopin scherzo finished, and a different scherzo, one by Mendelssohn, began. I’ve never liked Mendelssohn, he bores me.

By chance, the YouTube channel displayed a concert performance by Fazıl Say, the famous Turkish pianist. I clicked on it. He was performing Chopin’s “Nocturne, No. 16.” Since it was getting dark, I thought, why not? A bit of night music.

As the nocturne’s lovely, ascending and descending melody began, I helped Özge clear the table. We took the dishes to the kitchen and put them in the dishwasher. Then we went out to the balcony to drink our wine and have a cigarette.

The traffic had died down, and the street lights were lit as the sun set over the buildings. The dog had stopped barking and was lying down under his tree. I looked at my wife and she was lovely. Well, not every moment had to be absurd; one must make do with the quieter ones, the secluded hours. We drank the wine and listened to Fazıl Say’s performance.

We heard something. It was our neighbor, a woman in her seventies who is always cheerful and chatty. Usually in the evenings we can hear her talking with someone on the phone, her silver, infectious laugh passing like some impish spirit through the walls. Tonight she was singing, or humming rather, in the same high-pitched, shimmering voice. She was singing along to the “Nocturne.”

“We should have her over some night, for dinner,” I said.

“No, we’d never get rid of her,” my wife said.

“You’re probably right.”

The singing continued to pass through the walls, until suddenly it was cut off, or drowned out, by loud, mechanical sounds down in the street below. The garbage truck, which always passed about this time, was lifting up the dumpster with its noisy, hydraulic arm. The sound of the truck woke up the dog, who began barking incessantly again. A loud bang announced the bin’s arrival back on the sidewalk, and with a hiss, the truck clattered on. The dog kept barking, straining at his leash, until the truck was up the hill and out of sight.

It was then that I realized that I had been going about it all wrong. I had been looking for scherzos, when all along I should have been listening for them. Finally, I had heard a city scherzo:

It begins, high over the city at sunset. We hear busy traffic sounds, the horns blaring. Then we have the lyrical opening passages of Chopin’s “Nocturne,” as performed by Fazıl Say. The phrases are soon taken up by the old women in their lonely flats, and their silver voices join in unison, until the garbage trucks come along and drown them all out.

Lastly, heroically, the dog – barking, straining at his leash – chases away the villainous garbage truck, ending the scherzo with a sharp, staccato note. Now play it all back at twice the tempo. Finito!

James Tressler is a writer whose books, including “Conversations in Prague” and “Letters from Istanbul, Vols. 1 and 2,” can be found at Lulu.com. He lives in Koşuyolu.

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia