At a gathering of the elite doctors of the world, speaker after speaker demonstrates a miracle of medical science. An operation able to change a criminal’s fingerprints after every crime committed, a substance able to reattach the head of a mortally wounded soldier, a plastic surgery which transforms a pensioner back into her teenage self, and a Frankenstein’s monster of sorts composed of the remaining healthy organs of several donors. Each delegate at the conference agrees on the wondrousness of all the discoveries, sure to make a high profit. So, when the final doctor takes the stage and begins to describe a simple tonsil removal procedure, the audience chortles and insults the surgeon — it’s such a menial task that any doctor could easily perform. Until the man explains that he removed the tonsils through incisions in the throat as the patient was a member of the press who, in his country, are forbidden from even parting their lips. The audience is amazed, and agrees that this feat beats out the rest of the competition.

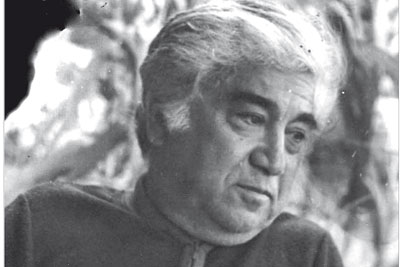

This burlesque presentation of the most eminent medical professionals of the world in their money-mongering and government-worshipping points out the major fears and foibles of society: crime, war, death and the greatest fear of all, freedom of the press. This story, “A Unique Surgical Operation,” was my first introduction to the satire of one of Turkey’s greatest writers, Aziz Nesin. A keen observer of the human plight and politics, Nesin fearlessly depicted both in his prose. He is king of the tragic-comedy that often is Turkish life: Whether describing a renter of a subterranean apartment two and a half levels below an apartment building who can find nothing but blessings in his cave or the family that realizes they’ve stumbled across government secrets in their groceries and, in desperation, tries to consume them all before their incrimination, Nesin shows the ridiculous contradictions of the world he lived in (many of which are still true today).

His powerful censure of dealings with the bureaucracy is perhaps born from his own experiences with them, beginning with the choosing of his name. When the government required every Turk to take a last name, he couldn’t make up his mind and often asked himself “Nesin?” What are you? In the end this became his last name. The government played a role in the donning of his first name as well. At birth, in 1915, his parents bequeathed the name Nusret to their son. However, Nusret had to join the military to continue his education and make ends meet, which didn’t match well with his desire for writing. Nesin adopted his father’s name, Aziz, to avoid the disapproving eye of his commanders. This resulted in a farce of confusion over the true identity of his father in life, and who had actually written his stories to receive royalties after his father’s death. After all, Aziz Nesin had died, so he had to prove to the government that he himself was the author.

Nesin writes an unapologetic critique of government and society with a socialist voice; this soon drew the wrath of the powers that were. In 1946, he was arrested for his publications, during which time the police tried to get a confession of the true identity of the writer from him, and two years later he had another stint in prison over writings that were not actually his own. For a time even his name became a talisman against publication; newspapers were wary of printing any of his submissions. Nesin began using even more pen names to continue the publication of his poems and essays. By swapping out identities, of which there are more than two hundred, he was able to continue to share his many poems, essays, stories and plays.

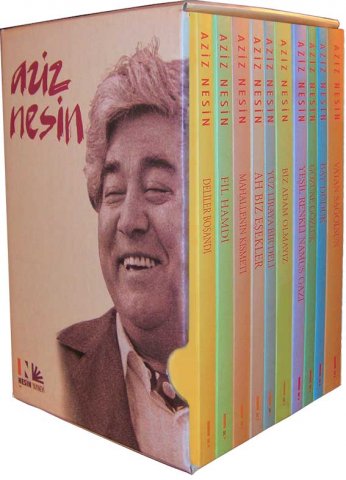

After winning his first major award, the 1956 Gold Palm Award for Humor in Italy, the pathway of his career cleared and the name Aziz Nesin stuck, growing in fame and popularity as the years passed. By his death Nesin’s stack of publications had surpassed his height, and since then he has become one of the best-selling Turkish writers in Turkey.

An activist in more than just his writing, Nesin promoted the right to free speech and fought against the plight of human suffering throughout his life. He was especially active in his fight against religious and government oppression. After the Kenan Evren-led military coup of 1980, he helped pen, along with other like-minded activists of the time, the “Petition of Intellectuals.” He also began a translation of the religiously divisive Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie, which led to an attempt on his life. His outspoken work was awarded with many human rights, democracy and freedom of speech awards.

Despite his success, Nesin never became a wealthy man nor ever wanted to be. He dedicated much of his time and funds to the Nesin Foundation, founded in 1972. The mission of his foundation is to help alleviate the suffering of children in destitute and dire circumstances. They began by accepting four such children every year and paying for their education, room and board from childhood through university. Upon his death, all royalties from his many publications for all time go directly to funding the humanitarian work of this foundation, now under the guidance of his son Ali Nesin and a graduate of the Nesin program, Süleyman Cihangiroğlu. The foundation also runs a Mathematic Village in Şirince.

This month the Nesin Foundation and the many fans of his works will celebrate the 100th birthday of this prolific writer on December 20. It’s a great opportunity to join in his remembrance by picking up one of his titles. The works have been translated into many languages including English, and can be ordered online or from bookstores around Istanbul. Other Nesin souvenirs are also available from the Foundation with all funds going to support their mission.

Meridith Paterson is a contributor to Yabangee

Great piece.