Although not overwhelming in its content, the Pera Museum‘s retrospective of Swiss artist, Alberto Giacometti (1901- 1966) is both impressive and comprehensive. Expertly curated, the show takes you through his entire career, which was essentially bifurcated by the Second World War. The show kicks off with a plaster bust of his brother, Diego – created when Giacometti was just 13 years old. This bust is a truly touching cornerstone to launch the exhibition, as it foreshadows numerous hallmarks of his lifelong career, namely; sculpture, portraiture, and the labored investigation of his loved ones. The show breezes though his early pseudo neo-impressionistic paintings, non-figurative sculptures and subsequent brush with surrealism, before unleashing his late period bronze figures and busts. This later, post-WWII section also includes a number of painted portraits, and finally, a collection of lithographs he made in Paris which became, in effect, a sort of final exercise.

The retrospective is chronological and leads with the aforementioned bust of Giacometti’s younger brother, Diego. Dominating the early career section (1916-1921) are his pseudo neo-impressionistic paintings, which are mainly portraits, many of them featuring family members. The works are charming in their small scale, bold color juxtaposition and blotchy, spotted application of paint. This application, a take on impressionism (Giacometti highly praised Cézanne), creates a fuzzy effect, not dissimilar to the aesthetic of his later figurative sculptures, which lack smooth edges and resist clear autonomy from their surroundings.

From there, we follow his transition away from the figure with more abstracted sculptures, which where embraced by surrealists. During this time (1922-1935), he also created drawings and writings within and for the surrealist (political) movement. In 1935, Giacometti circled back to the figure and began working from models again, which essentially led him to being expelled from the surrealist movement. According to the exhibition, he approached the figures with the aim of “depicting reality not as it was but as he was seeing it.” In other words, for Giacometti this turn back to the figure was not a turn away from surrealism. Surrealism can be seen in the compositions of some of his most famous works, such as the bronze figures and busts, that followed, including The Cage and The Forrest, both from 1950.

My relationship with Alberto Giacometti and his famed bronze figures has been a long one — we are old acquaintances. As an undergraduate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I was introduced to Walking Man (1960) and Tall Figure (1947), which are part of the permanent collection at the AIC. Formally learning about art history for the first time, these sculptures interrogated my 18-year-old mind, and in turn, I interrogated them. Is the long, lean man of Walking Man searching for something, is he walking to remember or to forget? Is he walking to or from his lover? Or, perhaps, he is he walking home, appearing on the horizon at twilight, the light curling around his body and emaciating his frame. Tall Figure, similarly elongated, stands motionless, yet does not lack for agency.

Giacometti’s sculptures, whether still or ‘in action,’ are self-possessed. Cast in bronze, they are impossibly thin, some life-sized in height, some larger, and they are striding, existing and meditating in the worlds’ complicated static. Their frail bodies, undeterred, remain rigid and purposeful. Agitated, with no smooth surfaces to define them, they remain calm. This uneasy delineation creates a magnetizing tension. For four years I viewed them almost once a week, on my way to and from class. Thus, seeing his late period sculptures at the Pera, I felt a warm relief and pleasant sense of recognition, like meeting the extended family of old friends. These bronze figures and busts are his most recognized works and, in the opinion of many, his best.

The artist’s post war investigation of the figure and form ushered in a number of portrait paintings, which are almost monochromatic. In line with his practice, they are all portraits of, or modeled after, his close friends and family. Art professor and critic Mark Van Proyan has said (in regards to self-portraiture, but I think it can be equally applied to portraiture), “The key to making a great [self-portrait] is having a very smart realization about how to portray two things at the same time, which is a ‘type’ of person, and a ‘specific’ person.” In this regard, he praises Rembrandt and Francis Bacon. It is my impression that Giacometti also shows a specific person in his portraits; indeed, one can recognize a number of busts from these portraits and vice versa. But he shows them as his own type of person, creating a sort of self-portrait in the process. When taking into account a number of paintings at once, one can seethe artist’s unique and consistent vision of his subjects.

Finally, a set of commissioned lithographs made in Paris are included in the show. They are an intimate look at his Paris existence, showcasing scenes from his everyday life, including his studio and the apartments of his wife and intimate friends. Created ‘on the spot’ with no correcting or reworking, they are the opposite of his laborious sculptures, which are worked and whittled in within, quite literally, an inch of their existence. The lithographs will surely be a delight to printmakers, Francophiles, and Giacometti enthusiasts. It is a successful exercise, but still an exercise more than a movement within his greater body of work, and one which does not show the true weight of his obsessive talents. While these ‘quick take’ drawings are lovely and biographical in a way that appeals to our voyueristic tendencies, I enjoy the fruits of his tedious labor more.

In the vast array of his work on display, his early and late period work resonates the strongest. The experiments of a young artist are brought off the page and further into our dimension through sculpture. Seeped in years of intense practice and simmered in surrealism, his late period bronze sculptures see him back to early investigations, which is to say, the core of his practice.

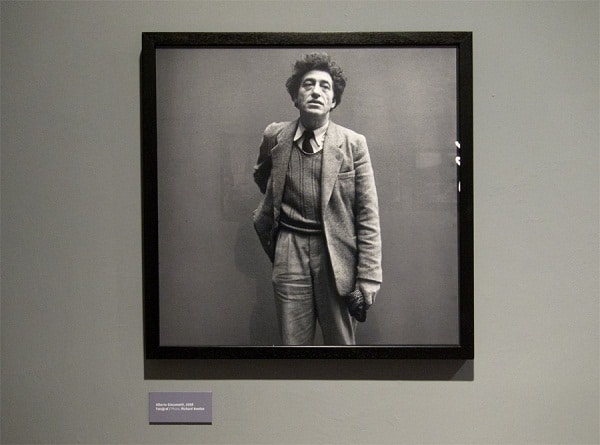

Beyond representing his work, this show includes a number of wonderful representations of the artist himself, which take the form of video and photographs. A short video, translated into English and Turkish, sees the artist describe his process and obsession with the optical precision of the eye. Also, many excellent photographic portraits of the artist, often in his studio, taken by Richard Avedon and others, sum up the show.

At the tail end of my visit, I went back to the beginning just in time to see a group of third graders enter the exhibition. I watched these kids as they looked at paintings and busts of children, made by an artist who was himself a child at the time. Some of these third graders will never encounter the work of Giacometti again in their lives. For others, it will be the beginning of a long relationship.

If, like these third graders, it will be your first experience viewing the work of this prolific and passionate artist, the exhibition is a must see. And if you have a long history with Giacometti? Well, then, you especially shouldn’t miss this show — it will be like meeting a talented old friend in his finest form.

You can learn more about the exhibition, which runs until Sunday 26 April, on the Pera Museum’s website. Keep up to date on all of the Pera Museum’s comings and goings by following them on Facebook and Twitter.

The Pera Museum is open from 10:00 am to 7:00 pm on Tuesday-Saturday, 12:00 to 6:00 pm on Sunday, and closed on Monday. Entry is 20 TL for adults and 10 TL for concessions. The museum is open and free of admissions from 6:00 to 10:00 pm every Friday.