If you went to university in the US, you may recall a movie night with friends laughing your head off at Cüneyt Arkın practicing Kung Fu kicks with boulders tied to his legs in a famous scene from “Turkish Star Wars” or “Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam.” One of the first things to catch viewers’ attention is how footage from Star Wars and music from Indiana Jones is placed directly into the film without any alteration. “Aren’t there laws against that?” everyone at the party asks in unison…

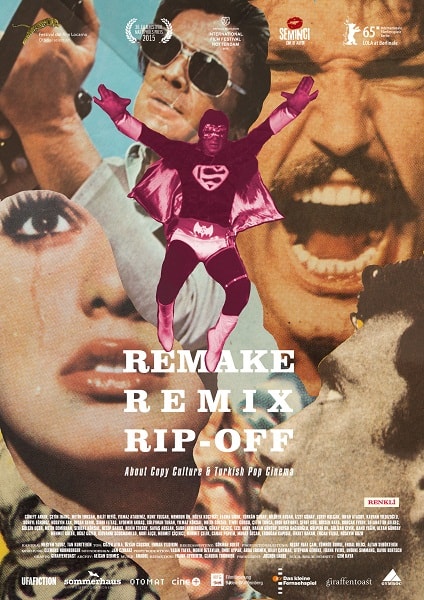

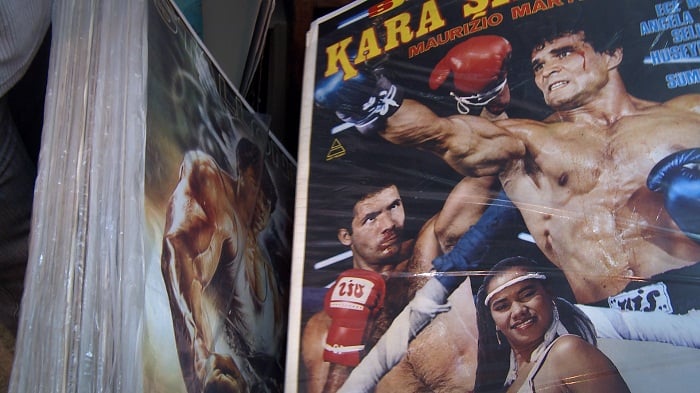

In his documentary “Remake, Remix, Rip-off” director Cem Kaya examines the widespread phenomenon of “copy culture” in the Yeşilçam era of Turkish cinema (1950-1990), which is often termed a “Wild West” in which no copyright laws applied and footage, music and storylines were all free for the taking.

How did you first encounter Yeşilçam cinema?

I became acquainted with Yesilçam cinema when I was a child, but I never watched it at the theater. We Turks living in Germany used to watch Turkish movies on video. In a way, Europe’s video craze of the ‘80s kept Yeşilçam alive; it was already in decline in Turkey.

What were your favorite films? Which scenes in particular stand out in your memory?

I didn’t have any favorite films. We watched anything we came across because we didn’t have the chance to learn much about films. The video cases didn’t even have the directors’ names on them, only those of the actors like Cüneyt Arkin or Türkan Şoray.

Apart from the videos we rented, we had a stock of films at home that we used to watch over and over again. So, some scenes are imprinted in my memory, like some of the really violent action scenes shot by Çetin İnanç in the ‘80s, and Ne Şeker Şey (“What a Sweet Thing”) by Osman Seden and similar comedies from the ‘60s.

How did you decide to make a documentary about this topic? How did those around you respond to the idea?

I decided to make the documentary in 2005 after finishing my master’s degree. My thesis was about remakes in Turkish cinema.

Those around me supported the idea a lot, but it was difficult to find a producer at first. The idea sounded great, but the archival work was too much for many producers. We had to watch so many films, had to clear royalties and get the clean screening prints of the films. It took me three years to find Jochen Laube, who was courageous enough to commit to a film with such a complex footage and research situation.

The documentary suggests that Turkish people have a stronger passion and appetite for cinema when compared to other peoples. What do you consider to be the reasons for this?

I think that the broad influence of cinema in Turkey has to do with the late arrival of television. The country’s climate is also well suited to open-air cinemas. Also, people didn’t just go to watch the films, but to socialize, as well. Don’t think of quiet movie theaters like we have today; the audience members would be chatting and reacting to the scenes. We could say they functioned as a collective viewer.

Were there any instances of copy culture prior to Yeşilçam cinema?

Copying at this time was a kind of local adaptation activity that can be traced back to novels of the Tanzimat period (1839-1876). For example, Ahmet Mithat’s novel “Çengi” tells the story of Don Quixote, but it is a very liberal interpretation.

The dubbing of foreign films during the 1930s and ’40s used to give people the sense that the films took place in Turkey. For example, the voice actor Ferdi Tayfur, who used to dub Laurel and Hardy’s films, would make the characters talk like two American tourists visiting Turkey. He would also change any jokes that Turks wouldn’t understand and add his own humor—not unlike a Hacivat-Karagöz puppeteer. In order to give some foreign films a local feel, belly-dancing scenes would also be added.

Many of the directors interviewed in the film claim to have made hundreds of movies. How was such massive output possible?

The number of cinemas in Anatolian villages increased in the 1950s with the coming of electricity. The entertainment tax had been lowered in 1948, making it possible to turn a profit by producing Turkish films. Thus, the demand for domestically produced films increased. However, the infrastructure for meeting this demand wasn’t sufficient, so Turkish filmmakers were dragged into a cycle of pulling from Turkish literature and foreign films for storylines.

Directors from this transition period, like Muhsin Ertuğrul and later on Faruk Kenç or Baha Gelenbevi, received education abroad and grew up watching foreign films in Turkey. They learned how to create cinema by copying the techniques of foreign films, which can be clearly seen in their work. There were no film schools in Turkey, so the industry had a master-apprentice system in which experience was passed down from generation to generation. Therefore, a specific kind of production system developed.

Using footage or music from foreign films was not illegal in Turkey. While copyright laws existed, works had to be registered. Because foreign producers didn’t register their scripts, music, and footage in Turkey, they were considered to be in the public domain—using today’s terminology—and free to be used.

Some people see this copy culture in Yeşilçam as quirky and loveable while others see it as an embarrassing reminder of a less-developed Turkey. How do you think it should be remembered?

What we call culture can’t exist without interaction. No culture is an entity in and of itself because it is founded on what came before it and other cultures with which it has interacted. There are also subcultures within it. No culture is ever static. In fact, they are all constantly evolving. Originality is something reserved for geniuses, but we mortals learn by copying from and being influenced by one another.

I believe that basing films on Western movies was a natural learning process, because cinema was a Western invention both technically and content-wise. It has a five-hundred-year history starting from the concept of the central vanishing point that emerged during the Renaissance and continuing on through the invention of the camera obscura, the illusion shows of Jesuit theater, romance literature, and the visual effects of today. Turkish cinema does not possess this sort of foundation in its past, but still Turkish people wanted to create films. They did this by watching Western films and using them as examples.

The 1980 coup signaled the beginning of the end for Yeşilçam. The film’s synopsis mentions that ‘neoliberalism’ had a role to play in that.

When the Özal government opened Turkey to foreign capital following the 1980 coup, the cinema industry was affected like all others. Theaters screening Turkish films had already dwindled. In 1988, Adnan Kahveci’s off-shore media project allowed American firms to establish their own distribution networks in Turkey. When the protections for the domestic market were lifted, American media firms began opening subsidiaries in Turkey. Thus, American films flooded the market, and theaters stopped showing Turkish movies.

Turning to cinema in general, filmmaking is a huge collective effort; however, the success of a film is generally credited to the director. Do you think this is unfair?

Metin Erksan says, “Cinema is an art created through the will of a single person.” The work is created collectively and everyone makes a contribution, but if the script is bad or if the director has no vision, it doesn’t matter if you have 1,000 people on hand, nothing good will come of it. If the success of a film is attributed to the director, it’s generally correct.

You are trained as a film editor. Could you explain the important but little-known contribution editors make to cinema?

I can only speak for documentary films with a narrative style. Here, a good editor should be able to tell a story in many ways, so he can make proposals to the director about how to develop a dramaturgy that enhances his project. Most directors are confused or overwhelmed by the hours of footage they have captured during filming. They behave like hunters who are literally out to shoot something. Even the same terminology is used when capturing footage. After the director brings the game home, the editor has to first clean up and then consolidate the footage. They then have to recommend ways to exhibit the very essence of what has been filmed. Often, the editor has to convince the director to throw away scenes that the director really likes. These scenes might have been hard or expensive to film, so there may be an emotional bond between the scene and the director. The editor has to offer a more objective perspective in order to contribute to the film’s narrative.

“Remake, Remix, Rip-off” will be screened on Sunday, April 13 at Akbank Sanat as part of the Meetings on the Bridge co-production market of the Istanbul Film Festival. Following the screening, director Cem Kaya will give a talk about creating films on a limited budget (the talk will be in Turkish, however).

The film will be screened at other upcoming festivals including the International Labor Film Festival and Documentarist. Yabangee will be sure to keep readers posted on the days and times of the screenings.