Anyone who has visited a kahvehane in Turkey has heard the sound of plastic dice dance across a wooden backgammon board. Though the game may seem simple—you move wooden chips across the board—people from Afghanistan to Eastern Europe are fascinated by it and play endlessly. The game is infamous for requiring the perfect balance of luck, in the form of a providential roll of the dice, and strategy, the player’s skill and willingness to take risks.

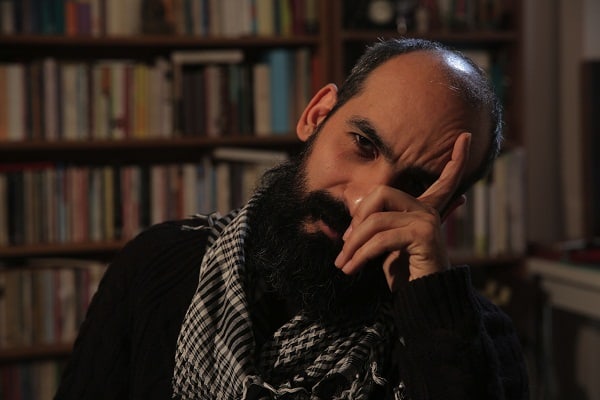

In the second part of the interview, Mehdi Shabani discusses the second film in his trilogy, ‘Şeş Beş,’ a documentary about backgammon and his latest film, ‘Meyhane: A Home for My Grandfather’ (Meyhane, Dedemin Can Evi).

What attracted you to backgammon as a topic for a documentary?

I’m a player. I really like to play games. Every kind of game. But backgammon is important for me because this game was created in this region and you can see it everywhere—Iran, Turkey, Egypt, Armenia, Georgia and so on. So, I became interested in why we play this game in this region. Is there any connection between our philosophy of life and this game? I wanted to investigate this question. Also, I play backgammon a lot; it’s one of my favorite games.

Generally, why do you love games so much? Why do you think games are important?

In my opinion, we are living only when we are playing. I don’t just mean playing games; our lives are a game, too. We are always in a game. We put ourselves out there and we take risks. You test yourself in a game. In Farsi, we say, “If you play a game, you have a chance to lose. But if you don’t play a game, you lose the game, actually.” You’ve already lost. So, in my opinion, not playing is a conservative way to live.

In my mind, protesting is a game, as well. We try to change things but being political is dangerous in this region. You go to a demonstration and you don’t know what is going to happen to you. So, you are actually playing a game. I think playing games is important for everyone because you can put yourself in a situation that is not part of your everyday life.

You can see the character of people when they are playing a game. This is because they are freer to do anything they want, say anything they want. So, you can sometimes just throw off whatever people use to cover up their real character.

To me, it seemed that some people in Şeş Beş were fatalistic, believing in the dice but at the same time not wanting to admit it.

This is the way I make my documentaries. I have someone describe an idea and they believe it completely. But after that, I cut to a scene showing them saying that it’s probably not completely true. I try to make a journey throughout the documentary and travel with the audience.

I suppose it’s open to interpretation. I thought the guy believes but didn’t want to admit it, although I guess you could also say that he wants to believe but finds it difficult. Where do you stand? Do you believe in the dice or do you believe in your strategy?

I believe that “chance” or “luck” is about the past. I can say I got lucky. But I can’t say I am lucky. We cannot find any “lucky” person anywhere around the world. I can say that I got a good chance but after that, I have to move with it. I have to create a strategy based on that lucky roll of the dice. I could calculate the probability of rolling a one and three if I needed it. I have to think about that and formulate my strategy. But, of course, the dice could come and destroy my whole strategy. So, in my opinion, you always have to be flexible in life, being prepared for the worst. You cannot say “I am lucky” or “unlucky” because who knows the future? Luck is about the past.

Turning to your latest film, you try to exhibit the culture of meyhanes and explain how it is in decline. Some people might be skeptical that meyhanes are disappearing given their high visibility–people are filling up the restaurants and even dining on the sidewalks.

If we think of meyhanes as places to drink and eat, they are just restaurants. I tried to describe what meyhanes are in literature. A meyhane is not just a place to drink. If you go back to Iranian or Turkish literature, meyhanes were a place to read poetry. Some people say it is not actually a place for drinking. It is a symbol of something else.

We can see that they are under attack from conservatism and from modernism. People want to go to bars and pubs. Like with hamams, you can see them everywhere but they are just for tourists. They are not a part of people’s everyday lives anymore. I think meyhanes are also not a part of life anymore. They’re just somewhere to go and eat; they’re just fancy restaurants. In fact, they’re so fancy and expensive that the kind of culture that we try to find in this documentary is no longer very visible. A meyhane is not just a place; it’s a culture. So, probably we will see meyhanes as places but without the culture.

Could you describe that culture?

It’s about being together. Again, collectivism. In meyhanes you open the door, go inside and find someone to talk to. Be part of a group.

You can see this in the layout of the meyhane–it should be like a circle. People should be able to talk from one table to another table. There has to be connection because it’s about sharing. But in the new way it’s about individualism. You go there and it’s “my table”, it’s “my privacy”, it’s “my space.” But in the traditional culture, the tables could talk to each other.

I tried to reflect this in the structure of the documentary; I tried to make my documentary like the meyhanes, getting words from one table and bringing them to another table in a different meyhane. I tried to make this documentary a place where people talk from different points of view. As your friends have said, meyhanes are visible but they don’t necessarily have the same culture. Is it good or bad? As a director of this documentary, I don’t want to judge. It’s up to the viewers.

What kind of factors do you think are responsible for these kinds of cultural shifts? Political factors? Economic factors? Social factors?

I think we can look at the situation from all of these angles. We lost meyhanes in Iran because of politics. We can see some new rules against drinking in Turkey. It’s about politics.

It’s about economics, too, because when alcohol is expensive or rakı is expensive, the type of people who go to meyhanes are different. Meyhanes used to be places for lower class and middle class people, not for the upper class. But now they’re for the middle class and the upper class. You cannot see lower class people in the meyhanes anymore.

At the same time, think about generational differences. People are trying to be more individualistic. A meyhane is not a good place for an individual. A meyhane is not a place for a person to go and be alone or pick up a girl or pick up a guy because it’s completely forbidden in meyhane culture.

There’s no space to pull someone away from the group.

Yes. So, that’s cultural.

Also, think about this: In advanced capitalism, everything should be chain stores—McDonalds, bars and so on. But meyhanes are the kinds of places that are run by one or two people. We can see these kinds of small places struggling to exist in the face of Istanbul’s betonlaşması or “becoming an asphalt jungle”, as they say. These kinds of places are struggling against this trend of making everything the same.

On the Facebook page for the film you wrote, “Cheers to the gardener who loves his winter more than his spring…” Could you explain this quote?

In Iranian drinking culture, we have a lot of things to say when making a toast. They usually remind us of someone who is not there. Meyhane culture or drinking culture in this region is usually very sad. It’s not about being happy and getting more energy to dance or something. It’s usually about drinking and thinking. In these cultures, we usually drink to remember something or to forget something. So, this quote shows an appreciation for someone who knows his “garden” or his “life” is going to be over but still tries to preserve something for himself to enjoy.

We usually make a toast to someone we like—someone we love—who is not there. We lost a lot of people during the movement, during the revolution, during the genocides and so on. Drinking and playing music is a bit sad in this region. So, this quote says that even if we live in this region in the worst times, we should be happy and try to wait for the spring. We live in winter now but we should know that there is a spring. Just wait for it. Work for the spring in your garden.

Meyhanes have disappeared in my country and they’re going to disappear from other countries, in my opinion. The documentary describes that situation. We should work to keep some part of our culture that is good, that we enjoy.

If you had to choose one, would you open a hamam, a kahvehane or a meyhane?

A meyhane. As a documentarist I really like to talk with people. My ears are open to listen to something interesting, strange or sometimes stupid, too. I’m really into stories and meyhanes is a really, really good places to listen to stories.

To learn more about Mehdi Shabani and his films, check out his website: http://www.mehdishabani.com/

You can read Part 1 of this interview here.

Better yet, you can attend a free screening of ‘Meyhane: A Home for My Grandfather’ at the Maltepe Belediyesi Türkan Saylan Kültür Merkezi (located a short walk away from the Gülsuyu metro stop on the Asian side) on Friday 19 December. The screening will begin at 7:00 pm. Anyone who would like a free invitation should call the Maltepe Belediyesi (0216 589 36 00) and reserve their seat at least one day before the screening. (Please Note: The film will have English subtitles.)

Dayla Rogers is a contributor to Yabangee

I loved this.

[…] The film will be screened on Wednesday 17 June at 7:00 pm at SALT Beyoğlu. Check out part 1 and part 2 of Mehdi’s […]